Philippa Ovenden

Among late-medieval songs, Lorenzo da Firenze’s Ita se n’er’a is known both for its Ovidian text, which describes the mythical tale of Pluto’s suit of Proserpina, and its eccentric notation.[1] Three versions of this song have survived, in London, British Library, Add. MS 29987, ff. 43v–44r (Lo) and two in Florence, MS Mediceo Palatino 87, ff. 45v–46r and 46v–47r (henceforth SqA and SqB). Of these, the notation of SqA has been the subject of much discussion, and disagreement, among scholars. The wide range of novel note shapes in this version, which include arrow- and circle-head semiminims, as well as semibreves and minims with appended circles (see Figures 1–2 below), have resulted in a range of different interpretations and transcriptions of the song.[2]

In his recent blog post, Davide Daolmi focuses upon the temporal dimensions of Ita se n’er’a.[3] Having already established his own idiomatic reading of the notation (Daolmi, 2020) of this challenging piece, he argues that the presence of a consistent temporal unit throughout the madrigale serves to illustrate the existence of a “regular unit of time” in fourteenth-century music, which he terms a musical tactus. Although the existence of tactus as a concept—albeit one with a variety of different manifestations—is well established in music of the fifteenth and sixteenth-centuries, scholars have hesitated to employ the term in relation to earlier compositions. Daolmi contends that while the term tactus was absent in fourteenth-century theory, the application of a consistent time unit across compositions such as Ita se n’er’a provided composers with the opportunity to convey different tempi through the use of the Italian trecento divisions. He draws on the testimony of the anonymous Italian author of the fourteenth-century Rubrice breves to argue that a faster tactus was employed in Italian repertory in the first half of the fourteenth century, but that this tactus slowed down over the course of the century in alignment with contemporaneous French practices. This reveals the possibility for both semibreves and breves to be employed as time units, as argued previously by Gozzi (2001).

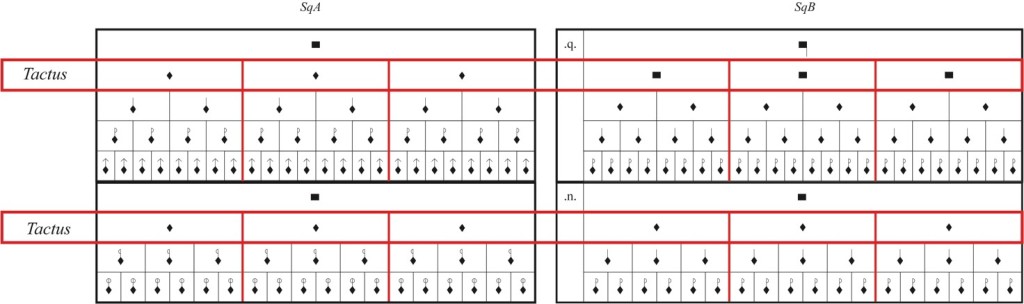

Daolmi’s choice of repertory presents a daunting task to the analyst. As a result of its extraordinarily complex notation, the precise temporal relationships between the individual note shapes of Ita se n’er’a are at times difficult to establish. The ambiguity of certain passages, along with a lack of standardization among the three copies, has led to a wide range of different readings of the song’s notation. Daolmi’s theorization of tactus in the madrigale rests upon equivalence between the two most prevalent divisions in the composition. Illustrated in Figure 1, these divisions see the longest time span in the composition—in SqA the breve—divided into twelve (ultimately twenty-four) parts or nine (ultimately eighteen) parts. SqB is notated using so-called Longanotation (see also Figure 1).[4] Here, what was in SqA the span of the breve becomes a longa when it is divided into twelve parts, composed of four breves each worth four minims. The scribe labels this the quaternaria (quaternary or fourfold) division. When the same breve span is divided into nine parts, it is labelled as a novenaria (novenary or ninefold) division. In the figure, the widths of the boxes graphically depict the relative duration of the sounds represented by each note shape. As marked in the figure, the tactus for Daolmi is the shared unit between the two temporal frameworks in the upper and lower parts of the grid. In SqA this is the span represented by the semibreve—one-third of the breve. In SqB, this is the span represented by the quaternaria breve—one-third of the quaternaria longa—or the novenaria semibreve. This equivalence is represented by the thick red lines in Figure 1.

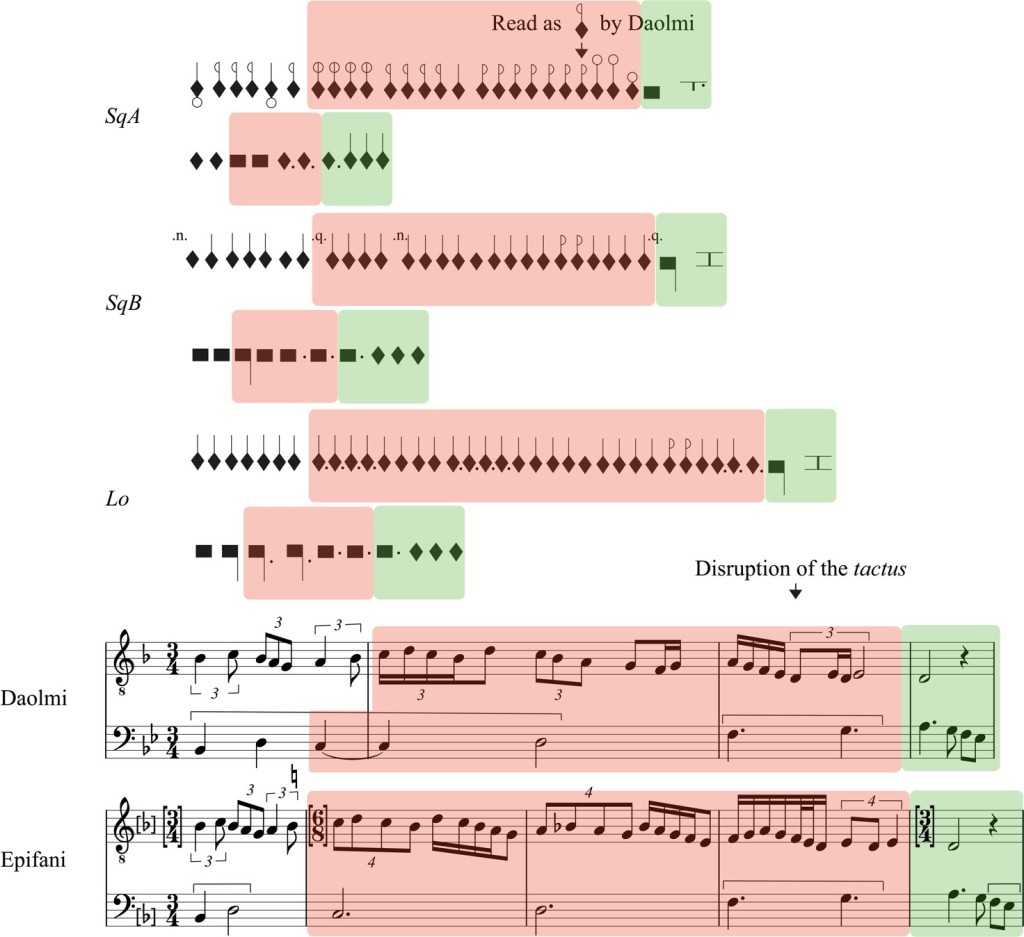

Although there is general agreement over the meaning of most of the note shapes employed in SqA—and specifically the note shapes included in Figure 1—the same cannot be said of all of them. Consider, for example, Figure 2, which transcribes the note shapes of the three versions of a particularly ambiguous phrase in the madrigale’s A section, and compares these with the transcriptions by Daolmi and Michele Epifani. A direct comparison between Daolmi’s and Epifani’s readings cannot be made because each author places a different level of emphasis upon the various copies of Ita se n’er’a to formulate a coherent transcription in modern staff notation. However, the figure nevertheless illustrates the challenge of adapting this ambiguous passage into the medium of modern notation, which demands that precise rhythmic values are ascribed to every note. As one may observe, Daolmi’s reading of these notes also includes a disruption of the shared time unit or tactus: worth 1 1/3 semibreves in the notational system of SqA, the semibreve with ascending circle cuts across the tactus unit.

The point of setting these readings side by side is not to discuss their relative merits, nor to contradict Daolmi’s assertion that a stable temporal unit is present in this composition. The momentary instability seen in the extract in Figure 2 does not undermine the relative equivalence that Daolmi identifies between the two most prominent divisions of this composition. However, that there should be so little agreement over the notation in this composition is worthy of further scrutiny. This disagreement extends not only to modern transcriptions, but also exists between each of the copies. Given the cultural context of Ita se n’er’a,this does not come as a surprise: a number of scholars have argued very compellingly that the complex notations of this period represent an attempt to codify improvisation, a position that Daolmi also supports.[6] It thus seems plausible that the disparity between the different versions may be reflective of the variety of performance.

Even if these copies represent an attempt to codify performance, this still begs the question of why there are so many apparent notational errors in the three copies, and in SqA in particular: it is impossible to transcribe this copy of the song into staff notation without reimagining some of the note shapes (see, for instance, Daolmi’s reimagining of the semiminim in Figure 2). The originals must be retrospectively “altered” to fit each note into the framework presented by our notational system. While this may represent incompetence on the part of scribes, an alternative explanation may be found, I would suggest, by taking note of the context of these seeming inconsistencies. Although they are internally ambiguous, the boundaries of all of these passages, including the extract in Figure 2, are marked by unambiguous temporal and contrapuntal junctures among the voices. In the case of Figure 2, the progression to the perfect consonance D–A (marked in green) provides an audible contrapuntal marker of stability that is also foregrounded visually by the breve in the cantus of SqA, and the longae of SqB and Lo. The preceding ambiguous note shapes represent momentary disorder before the certainty of this point of arrival and regrouping.

That the notationally ambiguous passages of this song should be visually and audibly compartmentalized in this way may indicate that a medieval reader would have placed less emphasis upon accurately representing the precise durations of notes than we tend to. Because the flourish in Figure 2 is characteristically improvisatory, we may surmise that there would have been some degree of freedom for the singer to render this ornament according to their own taste. In this scenario, the notation serves not to represent the precise values of temporal spans, but rather to indicate the boundaries and contour of the ornamental flourish. Any attempt to render such a passage in modern notation is by definition hindered by the medium of western staff notation, which demands that the editor must make a definitive decision about the durations of these notes, thereby obscuring the free, gestural quality of the original.

Daolmi’s assertion that there is a relative shared unit among the divisions of Ita se n’er’a, which he calls the tactus,is convincing. Such units also represent important markers for performers today, who must synchronize in ensemble and find equivalence between proportions. Without access visually to more than their own part, we may conjecture that finding common time units between differing divisions could have been even more important for medieval performers. Despite this, we should exercise caution before ascribing fixed and absolute time units to historical music in the form of tempo or metronome markings. The testimony of individual theorists such as Gaffurius who describe fixed tactus may point more readily towards a desire to establish theoretical standardzation than to describe performance. It is thus relative, not absolute time units or tactus that are important in this context.[7] In a similar vein, the ambiguity and lack of standardization present in the notation of songs such as Ita se n’er’a invites us to consider whether we should at times seek to confirm not an absolute reading of notationally complex repertory of this kind, but instead to embrace the relative flexibility that characterizes performance.

Sources Cited

Daolmi, Davide. “Ita se n’er’a star: Insights for a Fourteenth-Century Tactus (Ita se n’er’a star e un’ipotesi sul tactus nel trecento), Parts I & II.” In History of Music Theory, SMT Interest Group & AMS Study Group, 2021, trans. Giulia Accornero, https://historyofmusictheory.wordpress.com/2021/05/19/ita-se-nera-star-insights-for-a-fourteenth-century-tactus-ita-se-nera-star-e-unipotesi-sul-tactus-nel-trecento-part-i/; https://historyofmusictheory.wordpress.com/2021/05/19/ita-se-nera-star-insights-for-a-fourteenth-century-tactus-ita-se-nera-star-e-unipotesi-sul-tactus-nel-trecento-part-ii/.

—————-. “La notazione sperimentale di Ita se n’er’a star.” In Temporum Stirpis Musica, 2020, https://www.examenapium.it/meri/landini/lorenzo/lorenzo.html.

Deford, Ruth. Tactus, Mensuration, and Rhythm in Renaissance Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Epifani, Michele. “In margine alla notazione sperimentale del madrigale Ita se n’era a star di Lorenzo da Firenze.” Philomusica on-line 13 (2014): 59–88.

Flisi, Marco. “Notazione francese e italiana: Lorenzo da Firenze e la sperimentazione notazionale.” In Problemi e metodi della filologia musicale: Tre tavole rotonde, edited by Stefano Campagnolo. Didattica della filologia musicale, 21–27. Lucca: Lim, 2001.

Gozzi, Marco. “La cosiddetta ‘Longanotation’: Nuove prospettive sulla notazione italiana del trecento.” Musica Disciplina 49 (1995): 121–49.

—————-. “New Light on Italian Trecento Notation.” Recercare 13 (2001): 5–78.

Greig, Donald. “Ars Subtilior Repertory as Performance Palimpsest.” Early Music 31, no. 2 (2003): 196–209.

Long, Michael Paul. “Ita se n’era a star nel paradiso: The Metamorphoses of an Ovidian Madrigal in Trecento Italy.” In L’ars nova italiana del trecento VI: Atti del congresso internazionale “L’europa e la musica del trecento”, Certaldo, Palazzo Pretorio, 19-20-21 Luglio 1984: Sotto il patrocinio di Comune di Certaldo, edited by Giulio Cattin and Patrizia Dalla Vecchia, 257–68. Certaldo: Edizioni Polis, 1992.

Stone, Anne. “Glimpses of the Unwritten Tradition in Some Ars Subtilior Works.” Musica disciplina 50 (1996): 59–93.

von Fischer, Kurt. Studien zur italienischen Musik des Trecento und frühen Quattrocento. Das Repertoire. II. Repertoire-Untersuchungen. Bern: P. Haupt, 1956.

[1] For a discussion of the Ovidian elements of the song’s text, see: Long (1992).

[2] The most recent, more detailed commentaries have been conducted by Epifani (2014) and Flisi (2001).

[3] Daolmi (2021).

[4] The term Longanotation was coined by von Fischer (1956), and more recently has been discussed in depth by Gozzi (1995).

[5] Daolmi (2021); Epifani (2014), 81. For clarity, all the ligatures are written out as individual notes.

[6] See: Stone (1996); Greig (2003).

[7] See: DeFord (2015, 180–1).