In 1855, Sarah Mary Fitton (c.1796–1874) anonymously published a harmony book covering topics ranging from the rudiments of Western classical music theory to chromatic harmony. Structured as a series of thirty-six conversations between Mother and Edward, Conversations on Harmony was intended “to explain the rules of Harmony, in so simple a manner, as to bring their practical application within the reach of young students, and, also to increase the pleasure of mere lovers of music by enabling them to understand, in some degree, the theory of ‘sweet sounds.’”[1] The book was quite successful: it received praise from numerous critics, was printed in several editions, and was translated to French by Fitton herself and distributed in Paris. Fitton was likely born in Dublin and presumably educated by her father and the local organist. She worked as a governess and author throughout the UK and Paris, publishing children’s books, scientific works, and a primer on reading music.

Conversations on Harmony emerged at a time when musical literacy and effective pedagogical methods were of growing importance to the English public. Substantial parliamentary funding coupled with significant educational reform in the late 1830s ensured that most English citizens would learn the fundamentals of music in school. A plethora of singing schools and musical societies across the UK also attracted thousands of adult pupils from all social classes, and lectures by musical specialists drew massive crowds. By 1856, a London periodical noted that “Thousands have now some practical knowledge of the rudiments of harmony where hundreds did not possess it twenty years ago.”[2] During the same time period, the conversation book genre emerged as a pedagogical method that would be more effective than rote memorization. Music theory books structured as a dialogue between a student and teacher were certainly not a new idea. Conversations on Harmony, however, falls into a distinct genre of nineteenth-century instructional conversation books that were nearly all authored by Englishwomen and intended for educating children and the public on topics such as the political economy, mineralogy, church polity, and science.[3] Most of these books featured conversations between a mother and her children or a female teacher and her pupils.

Although a dialogue between a mother and child might be considered rudimentary or even insignificant, a closer examination of Conversations on Harmony reveals that Fitton was, in fact, actively engaged in some of the most critical midcentury scholarly discourses in the field of music theory. After thirty-five conversations on rudiments, harmony, melody, and voice-leading, Fitton concludes Conversations on Harmony with analyses of excerpts by Beethoven, Gluck, Haydn, and Mozart. Mother’s final remark to Edward is “And now you will not find it difficult to analyze, in the same manner, any piece of music, vocal or instrumental,” to which Edward responds: “I cannot tell you what pleasure it gives me, to be able to distinguish the nature of all the notes, of which music is composed.”[4] Perhaps this seems unsurprising given Fitton’s clear objectives in the book’s preface. Yet the study of harmony as a means of simply understanding music, rather than as a practical tool to aid in improvisation and composition, was a newly-emerging concept at the time. Until Albert Day’s 1845 Treatise on Harmony, most English harmony books were primarily thoroughbass and counterpoint manuals that were based on slightly expanded versions of Rameau’s theories.[5] Day’s radical new theories on free chromaticism resulted in the publication of numerous critiques in the ensuing decades, which formed a burgeoning body of scholarship focused more on harmonic analysis and theory than on thoroughbass and counterpoint. [6] As such, Conversations on Harmony was published at the perfect convergence of a progressively more musically literate public and the emergence of musical analysis as a scholarly discipline.

A noteworthy example of public music theory, Conversations on Harmony was repeatedly lauded for both its clarity and its inherent pedagogical value to students and teachers. The Daily News even asserted that the book filled a much-needed gap in the literature, noting that

“Treatises on the theory of music…when merely elementary, are too general in their explanations and too scanty in illustration to be of much service to anybody; and when more pretentious in design, they assume too much previous information…to suit the generality of amateurs. It has always appeared to us that there was still wanting a work on this subject more suitable to average comprehensions…This desideratum we think the ‘Conversations on Harmony’ has well supplied.”[7]

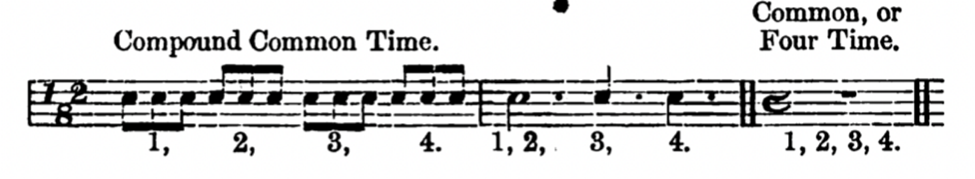

One particularly effective method that renders the book successful is the variety of conversational strategies Fitton employs to create a nuanced dialogue. For example, Mother occasionally provides an explanation of one concept that includes new terminology or notational symbols, naturally inspiring Edward to broach the next topic. When comparing compound and simple meters, Mother provides the following example of quadruple meters (Figure 1).

Edward then replies “In our last example of Common Time you forgot to write any notes in the bar.” Mother goes on to say “I placed a sign there, called a Rest, instead, which represents the value of that bar. A particular kind of sign, or rest, is used to supply the place of each sort of note…”[8]

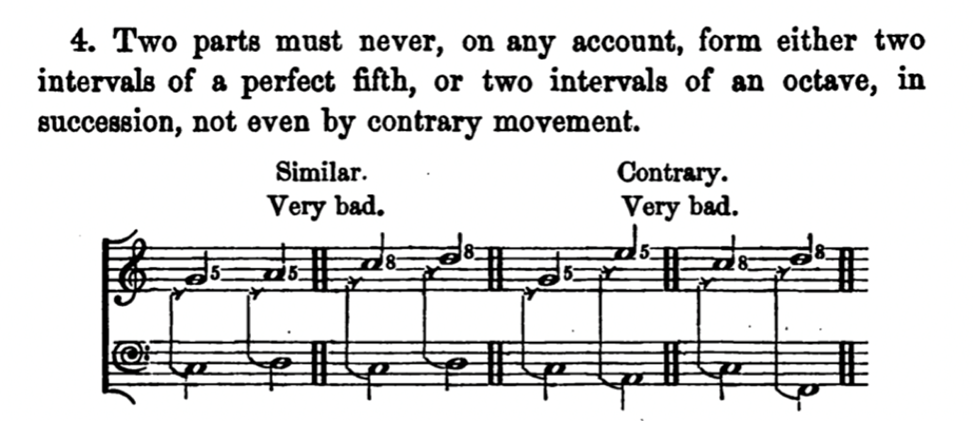

Perhaps Fitton’s most impactful contribution to nineteenth-century public music theory was the extraordinary clarity of her prose. The Musical World declared that “The rule of fifths and octaves is the pons asinorum of young musicians. We never before saw it so thoroughly well explained as in this [Fitton’s] treatise.”[9] The rule of fifths and octaves is explained by Fitton in five concise rules, each with an accompanying illustration. Fitton’s Rule #4, for example, is “Two parts must never, on any account, form either two intervals of a perfect fifth, or two intervals of an octave, in succession, not even by contrary movement.”[10] (Figure 2).

By contrast, Day writes four separate rules to illustrate this single concept, each of which is more verbose than Fitton’s one rule. For example, one of Day’s rules is “Octaves by contrary motion, or what is equivalent thereto, the progression from an octave to an unison or from an unison to an octave (though allowed by most writers), should not be used, as the richness of the harmony would be thereby destroyed.”[11]

Making complex harmonic concepts accessible to a broad public readership is no small task, and that Fitton’s Conversations on Harmony so successfully achieved this aim is a testament to her thorough understanding of effective pedagogical strategies and her skillful prose. Conversations on Harmony and other examples of public music theory call to mind issues of accessibility. Undergraduate harmony courses have often been used as a means of gatekeeping, yet many of the most advanced concepts in those courses are presented with extraordinary clarity in Fitton’s conversations. While there is no perfect way to reach every student, books like Conversations on Harmony can serve as critical reminders that there are many creative and accessible ways to teach “the theory of ‘sweet sounds.’”

Bibliography

Cherubini, Luigi. Cours de contrepoint et de fugue. Paris, c.1835.

Crotch, William. Elements of Musical Composition. London: Longman et al, 1812.

Day, Alfred. Treatise on Harmony. London: Harrison and Sons, 1885.

Fitton, Sarah Mary. How I Became a Governess. London: Griffith and Farran, 1864.

Fitton, Sarah Mary. Little By Little: A Series of Graduated Lessons in the Art of Reading Music. London: Griffith and Farran, 1863.

Fitton, Sarah Mary. Conversations on Harmony. London: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1855.

Fitton, Elizabeth and Sarah Mary Fitton. Conversations on Botany. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1817.

Herissone, Rebecca. Music Theory in Seventeenth-Century England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

“Literature.” Daily News (London),October 20, 1855.

Rainbow, Bernarr. Four Centuries of Music Teaching Manuals 1518–1932. Rochester, NY: The Boydell Press, 2009.

Rainbow, Bernarr. The Land Without Music: Muisical Education in England 1800–1860 and its Continental Antecedents. London: Novello and Company Limited, 1967.

“Review of Conversations on Harmony, by the author of Conversations on Botany.” The Musical World (London), November 17, 1855.

“Review of Conversations on Harmony.” Leicester Chronicle, November 3, 1855.

Shteir, Ann B. Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England, 1760–1860. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

[1] Sarah Mary Fitton, Conversations on Harmony (London: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1855), Preface.

[2] “Review of Conversations on Harmony,” Sharpe’s London Magazine of Entertainment and Instruction for General Reading,January 1856.

[3] Jane Marcet’s Conversations on Chemistry (1806) is the earliest known book in the genre, and numerous others followed in the following decades. Very few of the conversation books focus specifically on musical instruction, and of those that do, Conversations on Harmony is by far the most substantial.

[4] Fitton, Conversations on Harmony, 248.

[5] The Royal Academy of Music’s primary theory textbooks at the time, for example, were William Crotch’s 1812 Elements of Musical Composition and Luigi Cherubini’s 1835 Cours de contrepoint et de fugue.

[6] Bernarr Rainbow, Four Centuries of Music Teaching Manuals 1518–1932 (Rochester, NY: The Boydell Press, 2009), 225–6.

[7] “Literature,” Daily News, October 20, 1855.

[8] Fitton, Conversations on Harmony, 8.

[9] “Literature,” Daily News, October 20, 1855. Fitton’s book received at least eight substantial reviews in the months after it was published, most of which engaged substantially with the theoretical content of the book and praised Fitton’s clarity. On November 17, 1855, The Musical World’s review asserted that “It is quite equal to any book we know of its peculiar scope, and superior to many in its clear exposition of details. By its help, the young student will without doubt, gain a satisfactory foothold, at least, within the limits of a not easily accessible subject.” Likewise, the review of the book in the November 3, 1855 Leicester Chronicle praised Fitton’s “lucid simplicity” and elevated the book’s credibility by mentioning “two of the best judges of musical sciences:” Cipriani Potter (the Principal of the Royal Academy of Music and the book’s dedicatee” and Vincent Novello (the book’s printer).

[10] Fitton, Conversations on Harmony, 61.

[11] Alfred Day, Treatise on Harmony (London: Harrison and Sons, 1885), 12.