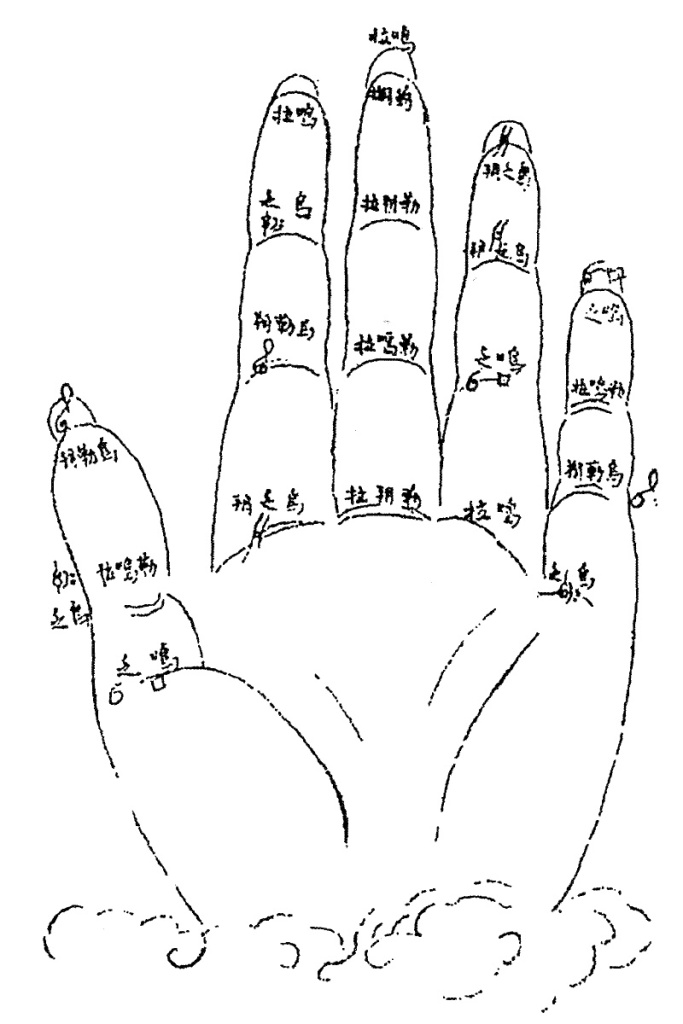

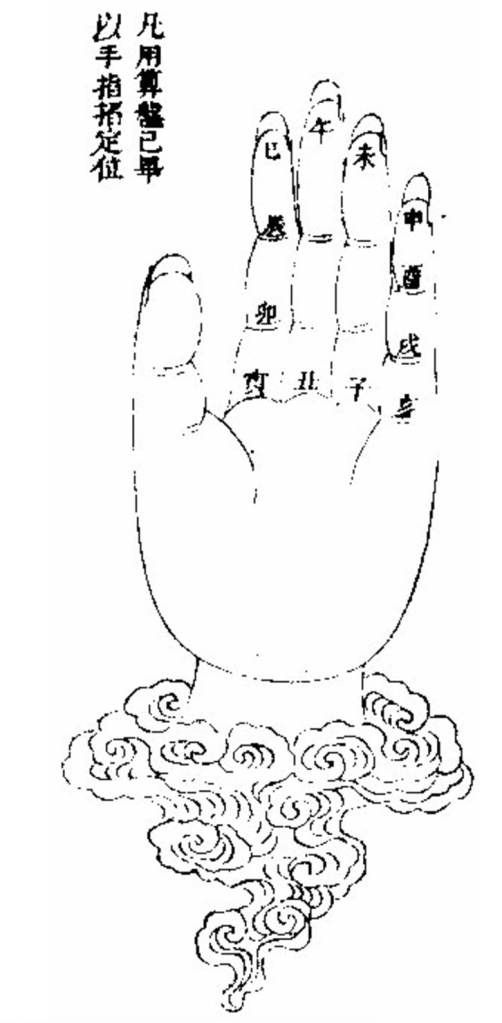

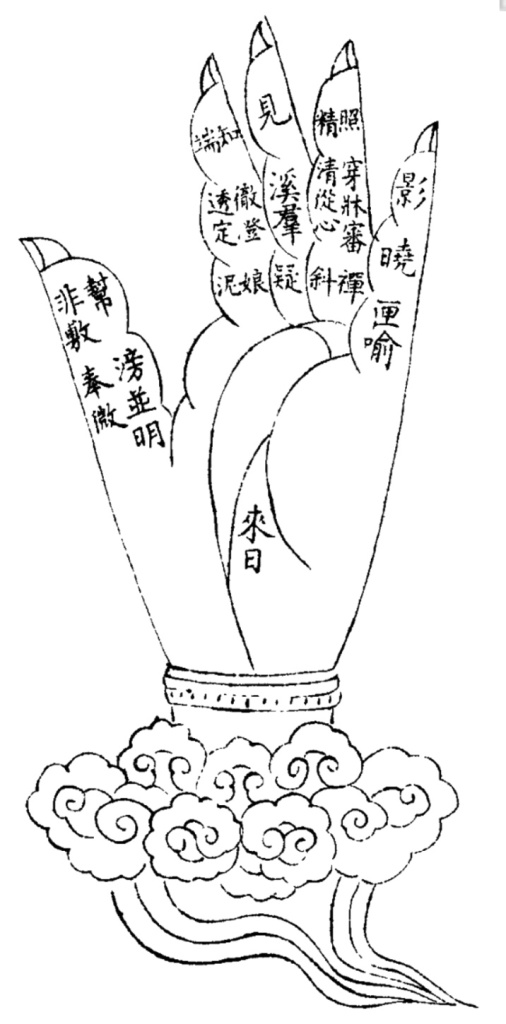

One of the global traces left behind by the Portuguese Jesuit missionary Tomás Pereira (1645–1708) in late seventeenth-century Beijing is a Guidonian Hand (Fig. 1). This handy mnemonic tool appears in his treatise Lülü zuanyao 律呂纂要 (c. 1680s, roughly translated as “A Compilation on Music”), which Pereira created for the Kangxi Emperor (1654–1722) as a primer introducing hexachordal solmization and rhythmic notation.1 Featured in the tenth chapter titled “An Explication on the Order of Note Names Inside the Palm” (Zhangzhong yueming xushuo 掌中樂名序說), this Chinese Guidonian Hand includes transliterated solmization syllables (voces) in Chinese (for example, fa wu 乏烏 is [F] fa ut), along with flat and natural signs and the G, F, and C clefs.

Fig. 1. A Guidonian Hand in Lülü zuanyao 律呂纂要, book 1, chapter 10, Zhangzhong yueming xushuo 掌中樂名序說 [An Explication on the Order of Note Names Inside the Palm] (c. 1680s), n.p.

Traditional Guidonian Hands follow a spiral pathway, while rarer variants in a “ladder” configuration, as described by Susan Forscher Weiss, feature pitches traveling vertically from one finger to another.2 The diagram in Lülü zuanyao represents a distinct variation of the spiral configuration that I call a “looping” Hand, which introduces an additional note on the thumb, emphasizing circularity over the finite, linear-range characteristic of spiral and ladder Hands. In this post, I explore the one-handed operation in Pereira’s looping Hand, examine its confluence with the similarly single-handed Chinese reckoning practice of qiasuan 掐算, and broadly consider the musical Hand as an instrument of music theory.

Looping Hand(s)

The Guidonian Hand is often a two-handed operation, perhaps best and most familiarly illustrated in the oft-reproduced example of Hélie Salomon’s Scientia artis musice (1274). In this illustration, the magister’s beefy index finger points towards his outsized left-hand with exaggerated proportions, magnificently spread out as a fleshly epistemological platform and didactic instrument (Fig. 2). As Stefano Mengozzi remarks, the Hand “was a sort of musical ‘palm pilot’ by which singers could quickly review the correct association of letters and syllables and the intervals between them”—much like Salomon’s finger-stylus would navigate the tonal space on his left-handed display.3

Fig. 2. Detail of Hélie Salomon, Scientia artis musice, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan MS D.75 (1274), fol. 3v.

Whether laid out as a spiral or segmented into finger-ladders, the Guidonian Hand features 19 or 20 loci or places on the gamut.4 The gamut begins with pitch 1 (Gamma ut) at the tip of the thumb and, after traversing through a spiral, concludes with pitch 19 (D la sol) at the middle finger’s top joint, or pitch 20 (E la), which is typically visualized floating above the middle finger (Fig. 3). Ladder Hands place pitches 19 and 20 respectively on the little finger’s tip and the space above (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 (left). Example of a spiral Hand. Giovanni Battista Caporali’s edition and translation of Vitruvius, De Architecture (Perugia: Bigazzini, 1536), fol. 111v. Yellow highlights added to illustrate notes ascending the gamut for Gamma ut. Fig. 4 (right). Example of a ladder Hand. Adam Gumpeltzhaimer, Compendium musicae, pro illius artis tironibus (Augsburg: Valentin Schönig, 1611), n.p.

The looping Hand in Lülü zuanyao, as well as other Iberian and North American examples, adds pitch 21 (F fa ut) at the exterior of the thumb’s upper joint. These sources suggest a global network of transmission facilitated by early modern Catholic missions.5 In the diagrammatic representations of Hands, pitches 20 (E la mi) and 21 (F fa ut) often appear as disembodied places floating outside their digits. Initially, I puzzled over the large gap that imposes an inelegant and seemingly illogical leap from above the top of the middle finger to the side of thumb, breaking the contiguity of the traditional spiral (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Pitches 20 (la ming 拉鳴, i.e., [E] la mi) on the exterior of the middle finger, and 21 (fa wu 乏烏, i.e., [F] fa ut) on the exterior of the thumb, as illustrated in the flattened diagram of the Guidonian Hand from Lülü zuanyao.

Diagrams like Pereira’s Hand in Lülü zuanyao may be understood as an example of “artificial flatness.” The philosopher and media theorist Sybille Krämer has identified this conceptual flattening as a cultural technique in which depth is eliminated: “only two registers of spatial order are projected onto the surface: right/left and over/under. … Flatness thus negates the unobservable and uncontrollable ‘behind’ and ‘below.’”6 Such a cognitive framework, as Krämer explains, allows for “a space of overview, control, and manipulability, as the graphic interaction of point, line, and plane enabled the visualization and observation of invisible, theoretical concepts.”7

While the diagrammatic representation in Lülü zuanyao serves as an example of artificial flatness par excellence, I will point out that not all Hand diagrams are fully flattened. The looping Hands in Mathias de Sousa Villalobos’s Arte de Cantochão (1688; Fig. 6) and Francisco Marcos y Navas’s Arte, ó Compendio general del canto-llano, figurado y organo, en método fácil (1776; Fig. 7), for example, convey a more fully developed sense of three-dimensional space through foreshortening, textured details, shading, and cross-hatching. Twirling ribbons in Marcos y Navas’s diagram wrap around the fingers and thumb to further enhance the sense of depth, while Sousa Villalobos’s Hand unambiguously depicts “E 20” and “F 21” inscribed upon banners emphatically placed behind the middle finger and thumb. Together, these features create a visual hierarchy, recovering the obscured “behind” in flattened diagrammatic representations.

Fig. 6 (left). Mathias de Sousa Villalobos, Arte de Cantochão (Coimbra: M. Rodrigues de Almeyda, 1688), 12. Fig. 7 (right). Francisco Marcos y Navas, Arte, ó Compendio general del canto-llano, figured y organo, en método fácil (Madrid: En la Imprenta de Don Joseph Doblado, 1776), 3.

To explain the gap between the middle finger and thumb, the flattened Hand needs to be peeled from the page and enfleshed. This unflattening requires a one-handed operation, as observed in Johannes Tinctoris’s Expositio manus (before 1475): “some people most aptly indicate the places on the thumb of the left hand with the index finger of the same hand and the places on the other fingers similarly by the thumb of the same hand; wherefore they may use only one hand, that is, the left…” (emphasis added).8

The back of the hand may be accessed with a three-dimensional shortcut by bending the fingers: for pitch 20 (E la mi) the thumb points to the back of the middle finger, and for pitch 21 (F fa ut), the middle or index finger points to the back of the thumb. The gamut technically concludes here, but the sequence continues with the tips of the index finger and thumb meeting to indicate pitch 1 (Gamma ut) or, I suggest, an insinuation of “pitch 22” (G sol re ut), continuing the gamut’s ascent. The numerical ordering of notes in some Hands indicates this relationship of F (at the back of the thumb) ascending towards G (at the tip of the thumb): the identical Hand diagrams in Adriano Banchieri’s Cartella (1601) and Orazio Scaletta’s Scala di musica (1626) show “1 F fa ut” proceeding to “2 Gamma ut.” In looping Hands, the circular design connects the two ends of the gamut-ladder, folding upon itself into a Möbius strip of sorts. This circularity is evident in Hands where the thumb’s tip is solmized not as Gamma ut, but rather, G sol re ut, as in the case of Marcos y Navas’s Hand. The gamut had already begun in medias res.9

In this framework of a one-handed looping Hand, pitches extend ad infinitum, breaking the limit of the gamut. Analogous to the ouroboros, the gamut devours its own tail in unending, regenerative cycles (Fig. 8).10

Fig. 8. Animated GIF of the author’s hand demonstrating an infinitely ascending gamut on a looping Guidonian Hand.

Chinese Hand Reckoning and Palm Diagrams

In the context of European iconography, a Guidonian Hand emerging from swirling clouds and adorned with long and manicured fingernails may appear striking, but such elements are common among Sinitic palm diagrams (zhangtu 掌圖). The historian of medicine Marta Hanson explains that such a “cloud-vapor pedestal” serves to convey the concept of qi 氣—the animating life force or vital energy that structures Chinese philosophy and medicine.11 Discussing the manuscript Putong Guji 15251 (c. 1707), a commonplace book that includes Lülü zuanyao, Lester Hu notes that the “exquisite fingernails” and “mystifying cloud” frequently appear in manuals for the Chinese zither guqin.12 I would add that these iconographic features also appear frequently in Sinitic treatises of mathematics and astronomy (Fig. 9), medicine (Fig. 10), rhyme books (Fig. 11), and divination manuals.13 The Guidonian Hand in Lülü zuanyao would have been one among the many hand mnemonics and palm diagrams familiar to the Sinitic literati.

Fig. 9 (left). The cycle of the twelve Earthly Branches. Dingwei zhangtu 定位掌圖 [Palm Positioning Diagram] from Chen Menglei 陳夢雷, ed., Gujin tushu jicheng lixiang huibian lifadian 古今圖書集成歷象彙編曆法典 [Imperial Encyclopedia, Astronomy and Mathematical Science] 1726, 125 juan. Fig. 10 (center). “Mnemonic of the Twelve Earthly Branches that Govern Heaven” in Liu Wenshu 劉溫舒, Suwen rushi yunqi lun’ao 素問入式運氣論奧 [On the Arcana of the Patterns of the Cyclical Phases and Qi in the Basic Questions]; illustration reproduced from Zhang Jiyu 張繼禹, ed., Zhonghua dao zang 中華道藏, vol. 20 (Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House, 2010), 628. Fig. 11 (right). Qieyun zhizhang tu 切韻指掌圖 [Finger-and-Palm Charts to the Cut Rhymes System], compiled by Sima Guang 司⾺光 (1019–86) et al., Shanghai, Commercial Press, 1934, 11b.

The writer of Lülü zuanyao—be it Pereira himself or perhaps a Chinese court amanuensis working with Pereira—employed the term qiasuan 搯筭14 (reckoning) to explain the utility of this diagrammatic arrangement:

“Using this arrangement of notes as shown in the illustration of the fingers [i.e., the drawing of the Hand], one can reckon (qiasuan 搯筭) with the loci of the fingers [zhijian 指間] to memorize the score, and verify the music as to which note from whence it begins, which note takes over, and which note concludes.”15

The finger-reckoning technique qiasuan (whence the phrase qiazhi yisuan 掐指一算, “to reckon with one’s fingers”) is a decidedly one-handed affair—see, for example, this fortune teller on the streets of Shanghai in 1926 or this sequence from the Hong Kong comedy movie My Lucky Star (Haangwan ciujan 行運超人, 2003) which features two feng shui masters (played by Ronald Kei and Tony Leung) in a zany display of mental calculation. At the end of the scene, reckoning serves as a mere gesture signifying cogitation. (Fig. 12).16

Fig. 12. Still from the film My Lucky Star (Haangwan ciujan 行運超人, 2003), featuring Tony Leung’s character demonstrating qiasuan hand reckoning.

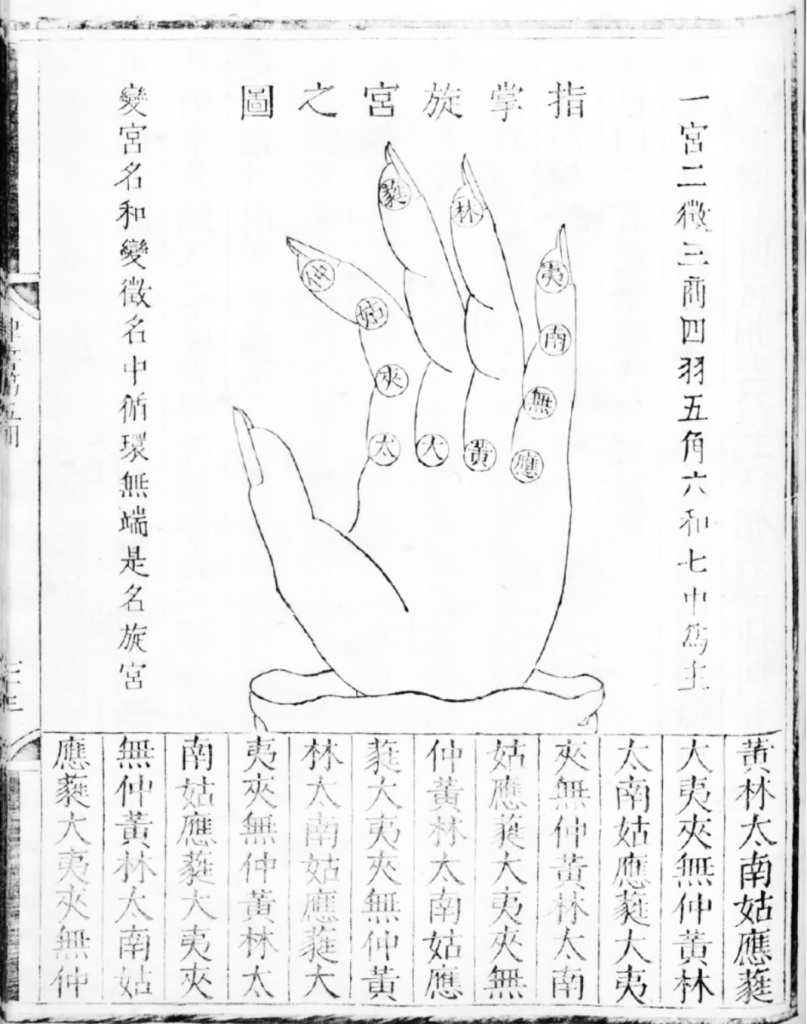

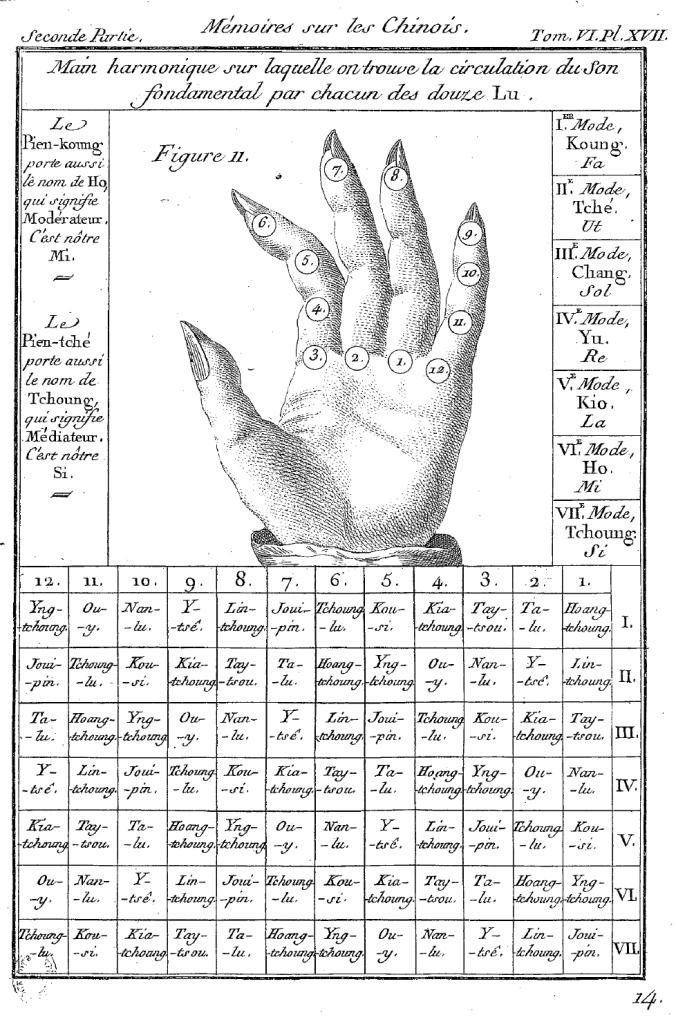

If Pereira’s looping Hand serves as a case study of European knowledge imported into China, there exists, conversely, a similarly one-handed musical mnemonic exported from China to Europe, likewise facilitated by the Jesuit global network. The hand-diagram in the music treatise Lülü jingyi 律呂精義 [Precise Principles of the Musical Pitches] (1596) by the Ming-dynasty prince Zhu Zaiyu 朱載堉 (1536–1611) superimposes the twelve Chinese musical pitches or lü 律 upon the traditional counting framework of the twelve earthly branches (dizhi 地支), plotted in a clockwise loop (Fig. 13).17 Zhu’s Chinese musical Hand would later reach European readers through Jean Joseph Marie Amiot’s (1718–93) Mémoire sur la musique des chinois (1779; Fig. 14) in an imitative rendering closely replicating the visual elements of the original: Zhu’s sleeve, curvature of the fingers, as well as the exquisite fingernails. Amiot, a Jesuit who resided in Beijing from 1751 until his death some four decades later, remarks in his Mémoire that “this way of counting is very easy for a Chinese person, because he is accustomed from childhood to count on his fingers in this way the years of the cycle and to assign the interval between one epoch or date or another.”18

Fig. 13 (left). Zhu Zaiyu 朱載堉, Lülü jingyi 律呂精義 [Precise Principles of the Musical Pitches], 1596, juan 5, 37a. Fig. 14 (right). Jean Joseph Marie Amiot, Mémoire sur la musique des chinois, tant anciens que modernes, ed. Philipp-Joseph Roussier (Paris: Nyon, 1779), Figure 11, Tome VI, Plate XVII.

Indeed, for the writer of Lülü zuanyao, the ubiquity of qiasuan reckoning, a common technique once taught to children as Amiot observed, succinctly captured—and arguably subsumed—the European practice of tracking pitches upon the hand as another Chinese reckoning. The cultural technique of the Western Guidonian Hand in Lülü zuanyao thus became one among the many East Asian traditions of palm diagrams and hand mnemonics.

Hand as Instrument of Music Theory

“All too often,” Alexander Rehding remarks, “the instruments that music theory handles are overlooked; they seem somehow ‘neutral.’” If an instrument of music theory like the keyboard and monochord is often regarded uncritically as a “transparent device,” then the hand likewise assumes a mantle of neutrality and transparency.19 Indeed, all the mental switches and toggles of the Guidonian Hand remain hidden in the mind: it has neither physical strings to pluck nor keys to play.20 But conceptualized as an epistemic tool, the hand becomes a musical instrument that “musical theory handles,” to draw on Rehding’s turn of phrase. The historian of medicine Shigehisa Kuriyama remarks that “the true structure and workings of the human body are, we casually assume, everywhere the same, a universal reality. But then we look into history, and our sense of reality wavers.”21 Hands, likewise, in their particular milieu, are not neutral or universal in either their chiro-topographies or their cultural specificities. Located at the intersection between artificially flattened diagrams, transcultural practices of (one-handed) reckoning, a chiro-visual method of eliciting voices,22 and a mnemonic that draws upon self-reinforcing haptic memory and reflexive tactility (self-touch), I suggest the musical Hand is not merely an interfacing appendage but an instrument in its own right.

I am deeply grateful for the guidance of Andrew Hicks, Carmel Raz, Roger Moseley, Annette Richards, Suyoung Son, Ding Xiang Warner, and the editors of this Blog. I have also benefited from the fellow participants of Suyoung Son’s “History of Book in China” seminar and Roger Moseley’s Media Studies directed study. Portions of this post appeared as papers presented at Instruments of Global Music Theory: A Symposium (May 19–20, 2023, Princeton University) and the “Early Sacred/Liturgical Musics and Digital Humanities: Skills and Resources” panel at the American Musicological Society 89th Annual Meeting (November 9–12, 2023, New Orleans).

Bibliography

Amiot, Jean Joseph Marie. Mémoire sur la musique des chinois, tant anciens que modernes. Edited by Philipp-Joseph Roussier. Paris: Nyon, 1779.

Banchieri, Adriano. Cartella, overo regole utilissime à quelli che desiderano imparare il canto figurato. Venice: Giacomo Vincenti, 1601.

Canguilhem, Philippe. “Singing Upon the Book According to Vicente Lusitano.” Translated by Alexander Stalarow. Early Music History 30 (2011): 55–103.

Chen Menglei 陳夢雷, ed., Gujin tushu jicheng lixiang huibian lifa dian 古今圖書集成曆象彙編曆法典 [Imperial Encyclopaedia, Astronomy and Mathematical Science], 1726.

Chen Sui-Yen 陳綏燕 and Yi Hsuan Ethan Lin 林逸軒. Dongfang yuezhu ─ baihua Lülü zuanyao 東方樂珠 ─ 白話律呂纂要 [Eastern Musical Pearl: Lülü zuanyao in the Vernacular]. Taipei: Elephant White Cultural Enterprise 白 象 文化, 2022.

Dyer, Joseph. The Scientia artis musice of Hélie Salomon: Teaching Music in the Late Thirteenth Century: Latin Text with English Translation and Commentary. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018.

Early Music Sources, “Solmization and the Guidonian Hand in the 16th Century,” YouTube video, 20:56. July 27, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRDDT1uSrd0.

Franciscanos. Regla de N.S.P.S. Francisco y breve declaracion de sus preceptos para su mejor observancia, y facil inteligencia con vna instruccion para los novicios de la religion del N. Padre San Francisco, y breve explication del canto llano con otras advertencias curiosas y necesarias. Dispuesta, y ordenada por el Padre Fr. Manvel Sanchez, predicador, y maestro de novicios del Convento Grande de N. Padre San Francisco de México. Mexico: Joseph Bernardo de Hogal, 1725.

Fose, Luanne Eris. “The Musica Practica of Bartolomeo Ramos de Pareia: A Critical Translation and Commentary.” PhD diss., University of North Texas, 1992.

Gild-Bohne, Gerlinde. “Mission by Music: The Challenge of Translating European Music into Chinese in the Lülü Zuanyao.” In In the Light and Shadow of an Emperor: Tomas Pereira, S.J. (1645–1708), the Kangxi Emperor and the Jesuit Mission in China, edited by Artur K. Wardega and Antonio Vasconcelos de Saldanha, 532–45. Newcastle uponTyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012.

Gumpeltzhaimer, Adam. Compendium Musicae, pro Illius Artis Tironibus. Augsburg: Valentin Schönig, 1611.

Hanson, Marta E. “Hand Mnemonics in Classical Chinese Medicine: Texts, Earliest Images, and Arts of Memory.” Asia Major 21, no. 1 (2008): 325–57.

_____. “From Under the Elbow to Pointing to the Palm: Chinese Metaphors for Learning Medicine by the Book (Fourth-Fourteenth Centuries).” BJHS Themes 5 (2020): 75–92.

Homola, Stéphanie. “Ce que la main sait du destin. Opérations et manipulations dans les pratiques divinatoires chinoises.” Ethnographiques.Org 31 (2015), https://www.ethnographiques.org/2015/Homola.

_____. The Art of Fate Calculation: Practicing Divination in Taipei, Beijing, and Kaifeng. New York: Berghahn Books, 2023.

Hu, Zhuqing (Lester). “A Princely Manuscript at the National Library of China — Part I: Guido’s Hexachords and the 18th-Century Chinese Opera Reform.” History of Music Theory (blog), February 1, 2019.

_____. “From Ut Re Mi to Fourteen-Tone Temperament: The Global Acoustemologies of an Early Modern Chinese Tuning Reform.” PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2019.

Klasing Chen, M. “Memorable Arts: The Mnemonics of Painting and Calligraphy in Late Imperial China.” PhD diss., Leiden University, 2020.

Kok, Vincent, director. My Lucky Star (Haangwan ciujan 行運超人). Orange Sky Golden Harvest, 2003. 1 hr., 40 min.

Krämer, Sybille. “Reflections on ‘Operative Iconicity’ and ‘Artificial Flatness.’” In Image, Thought, and the Making of Social Worlds, edited by David Wengrow, 251–72. Heidelberg: Propylaeum, 2022.

_____. “The Cultural Technique of Flattening: An Essay Introducing and at the Same Time Revising an Idea.” Metode 1 “Deep Surface” (2023): 2–18.

Kuriyama, Shigehisa. The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. New York: Zone Books, 1999.

Marcos y Navas, Francisco. Arte, ó Compendio general del canto-llano, figurado y organo, en método fácil. Madrid: En la Imprenta de Don Joseph Doblado, 1776.

Martín y Coll, Antonio. Arte de canto llano, y breve resumen de sus principales reglas para cantores de choro. Madrid: por la Viuda de Juan García Infanzón, 1714.

Mengozzi, Stefano. The Renaissance Reform of Medieval Music Theory: Guido of Arezzo Between Myth and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Moseley, Roger. Keys to Play: Music as a Ludic Medium from Apollo to Nintendo. Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.

Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Nunes da Silva, Manuel. Arte minima: que com semibreve prolaçam tratta em tempo breve, os modos da maxima, & longa sciencia da musica. Lisbon: Na officina de Joam Galram, 1685.

[Pereira, Tomás]. “Lülü zuanyao erjuan: Gugong bowuyuan tushuguan canggaoben” 律呂纂要二卷 : 故宮博物院圖書館藏稿本 [Lülü zuanyao, Two Volumes: Palace Museum Library Manuscript Facsimile]. In 四庫全書存目叢書 Siku Quanshu cun mu congshu [Siku Quanshu Catalog Series], 185:803–45. 濟南 Jinan: 齊魯書社 Qilu Shushe [Shandong Qilu Press], 1997.

Scaletta, Orazio. Scala di musica molto necessaria per principianti. Venice: Alessandro Vincenti, 1626.

Rehding, Alexander. “Three Music-Theory Lessons.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 141, no. 2 (2016): 251–82.

Seay, Albert. “Expositio Manus of Johannes Tinctoris.” Journal of Music Theory 9, no. 2 (1965): 194–232.

Sima Guang 司馬光 et al. Qieyun zhizhang tu 切韻指掌圖 [Finger-and-Palm Charts to the Cut Rhymes System]. Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1934.

Sousa Villalobos, Mathias de. Arte de Cantochão. Coimbra: M. Rodrigues de Almeyda, 1688.

Wang Bing 王冰. “Lülü zuanyao zhi yanjiu” 《律呂纂要》之研究 [A Study on Lülü zuanyao]. Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 102, no. 2 (2002): 68–81.

_____. “Lülü zuanyao neirong laiyuan chutan” 《律呂纂要》內容來源初探 [An Exploration of the Original Sources of Lülü zuanyao]. Studies in the History of Natural Sciences 自然 科學史研究 33, no. 4 (2014): 411–26.

Weiss, Susan Forscher. “Disce manum tuam si vis bene discere cantum: Symbols of Learning Music in Early Modern Europe.” Music in Art 30, no. 1/2 (2005): 35–74.

Zhang Jiyu 張繼禹 ed., Zhonghua dao zang 中華道藏, vol. 20. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House, 2010.

Notes

- On the content and genealogy of Lülü zuanyao, see Wang Bing 王冰, “‘Lülü Zuanyao’ zhi yanjiu 《律呂纂要》之研究 [A Study on Lülü zuanyao],” Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 102, no. 2 (2002): 68–81, and Gerlinde Gild-Bohne, “Mission by Music: The Challenge of Translating European Music into Chinese in the Lülü zuanyao,” in In the Light and Shadow of an Emperor: Tomas Pereira, S. J. (1645–1708), the Kangxi Emperor and the Jesuit Mission in China, ed. Artur K. Wardega and Antonio Vasconcelos de Saldanha (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 532–45. For a translation in modern vernacular Chinese, see Chen Sui-Yen 陳綏燕 and Yi Hsuan Ethan Lin 林逸軒, Dongfang yuezhu ─ Baihua Lülü zuanyao 東方樂珠 ─ 白話律呂纂要 [Musical Pearl of the East: Lülü zuanyao in the Vernacular] (Taipei: Elephant White Cultural Enterprise 白象文化, 2022). ↩︎

- See Susan Forscher Weiss, “Disce manum tuam si vis bene discere cantum: Symbols of Learning Music in Early Modern Europe,” Music in Art 30, no. 1/2 (2005), 35–74: 52. Examples of ladder Hands appear in Vicente Lusitano, Introduttione facilissima, et novissima, di canto fermo, figurato, contraponto semplice, et in concerto (Rome: Antonio Blado, 1553); Christoph Praetorius, Erotemata Musices in Usum Scholae Luneaburgensis (Wittenberg: Johannes Schwertel, 1574); Aurelio Marinati, La prima parte della somma di tutte le scienze nella quale si tratta delle sette arti liberali, in modo tale che ciascuno potrà da se introdursi nella grammatica, rettorica, logica, musica, aritmetica, geometria, & astrologia, di Aurelio Marinati (Roma: appresso Bartholomeo Bonfadino, 1587); and Orazio Scaletta, Scala di musica molto necessaria per principianti di Orazio Scaletta da Crema (Venezia: Alessandro Vincenti, 1656). ↩︎

- Stefano Mengozzi, The Renaissance Reform of Medieval Music Theory: Guido of Arezzo Between Myth and History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 4. ↩︎

- A single locus may include two pitches; e.g. B-flat and B-natural occupy the same locus. ↩︎

- Hands with pitch 21 (F fa ut) at the exterior of the thumb are found in Manuel Nunes da Silva, Arte minima (Lisbon: Na officina de Joam Galram, 1685); Regla de N.S.P.S. [Norma Sanctorum Patrum Franciscanorum] (Mexico: Joseph Bernardo de Hogal, 1725); Francisco Marcos y Navas, Arte, ó Compendio general del canto-llano, figurado y organo, en método fácil (Madrid: En la Imprenta de Don Joseph Doblado, 1776); and identical murals at the Franciscan Mission San Antonio de Padua (Jolan, California) and Mission San Luis (Tallahassee, Florida). ↩︎

- Sybille Krämer, “Reflections on ‘Operative Iconicity’ and ‘Artificial Flatness,’” in Image, Thought, and the Making of Social Worlds, ed. David Wengrow (Heidelberg: Propylaeum, 2022), 262. ↩︎

- Ibid., 269. ↩︎

- “Indice manus dextrae loca in ipsa manu sinistra aptius indicantur, licet nonnulli loca pollicis sinistrae manus indice eiusdem et loca caeterorum digitorum pollice similiter eiusdem aptissime indicent. Quo fit ut unica manu, scilicet sinistra, in traditione huiusmodi doctrinae utantur.” Quoted in Luanne Eris Fose, “The Musica practica of Bartolomeo Ramos de Pareia: A Critical Translation and Commentary” (PhD diss., University of North Texas, 1992), 103; translation from Albert Seay, “The Expositio manus of Johannes Tinctoris,” Journal of Music Theory 9, no. 2 (1965): 200–1. ↩︎

- Looping hands with G sol re ut at the thumb’s tip appear in Lülü zuanyao; Martín y Coll, Arte de canto llano (1714); and Marcos y Navas, Arte, ó Compendio general del canto-llano, figurado y organo, en método fácil (1776). ↩︎

- I am grateful to Loren Ludwig for suggesting the idea of the ouroboros. ↩︎

- Specifically, Hanson argues the inscriptions on Chinese hand mnemonic diagrams emerging from such qi-clouds serve as individual constituents to collectively articulate “the natural order of things”: “Using grammar as a metaphor, one could also argue that the swirling clouds convey the mass noun—a capitalized ‘Qi’—and the characters written on the hand break down the particular types of the mass noun lower case ‘qi’—that characterized seasonal change each year.” See “Postscript: The Meaning of Clouds and the Logic of Writing on Hands” in Marta E. Hanson, “Hand Mnemonics in Classical Chinese Medicine: Texts, Earliest Images, and Arts of Memory,” Asia Major 21, no. 1 (2008): 347. ↩︎

- Zhuqing Lester Hu, “A Princely Manuscript at the National Library of China — Part I: Guido’s Hexachords and the 18th-Century Chinese Opera Reform,” this blog, February 1, 2019, https://historyofmusictheory.wordpress.com/2019/02/01/a-princely-manuscript-at-the-national-library-of-china-part-i-guidos-hexachords-and-the-18th-century-chinese-opera-reform/, and “From Ut Re Mi to Fourteen-Tone Temperament: The Global Acoustemologies of an Early Modern Chinese Tuning Reform” (PhD diss., Chicago, University of Chicago, 2019), 27. ↩︎

- See also Marta E. Hanson, “From Under the Elbow to Pointing to the Palm: Chinese Metaphors for Learning Medicine by the Book (Fourth–Fourteenth Centuries),” BJHS Themes 5 (2020): 75–92. On divination practices, see Stéphanie Homola, “La fabrique des restes : réflexions sur les procédures aléatoires produisant des restes dans les arts divinatoires chinois,” Anthropologie et Sociétés 42, no. 2–3 (2018): 37–68, and The Art of Fate Calculation: Practicing Divination in Taipei, Beijing, and Kaifeng (New York: Berghahn Books, 2023). ↩︎

- 搯筭 are graphic variants in “vulgar” or common form of 掐算. 筭 has the same pronunciation with 算; the graph 搯 is pronounced tao in Mandarin when used as an older form of tao 掏 in standard form, and qia when used as vulgar form of 掐. ↩︎

- “將此排於所書指間樂名序之衆音諸啓發之次第能於指間搯筭熟記樂圖於指間查對即可侗晰其樂之以何音始以何音接以何音終矣.” Lülü zuanyao er juan: Gugong bowuyuan tushuguan canggaoben 律呂纂要二卷 : 故宮博物院圖書館藏稿本 [Lülü zuanyao, Two Volumes: Palace Museum Library Manuscript Facsimile], in 四庫全書存目叢書 Siku Quanshu cun mu congshu [Siku Quanshu catalog series], vol. 185 (Jinan: 齊魯書社 Qilu Shushu [Shandong Qilu Press], 1997) 815. [My translation.] ↩︎

- Qiasuan reckoning on screen is often a gesture latent with performative labor. On the labor and virtuosity of the “zany” as an aesthetic category, see Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012). ↩︎

- See M. Klasing Chen, “Memorable Arts: The Mnemonics of Painting and Calligraphy in Late Imperial China” (PhD diss., Leiden University, 2020), 53. Zhu’s musical Hand employs the same clockwise pathway in the Chinese palm diagrams seen in Figs. 9 and 10, beginning with the fundamental tone or Yellow Bell (huangzhong 黃鐘) mapped on zhi 子, the first earthly branch located at the bottom of the ring finger. ↩︎

- “Cette manière de compter est très-aisée pour un Chinois, parce qu’il est accoutumé dès l’enfance à supputer ainsi sur ses doigts, les années du cycle, pour pouvoir assigner sur le champ l’intervalle d’une telle époque, d’une telle date, à telle autre.” Jean Joseph Marie Amiot, Mémoire sur la musique des chinois, tant anciens que modernes, ed. Philipp-Joseph Roussier (Paris: Nyon, 1779), 123. [My translation.] ↩︎

- Alexander Rehding, “Three Music-Theory Lessons,” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 141, no. 2 (2016), 261–62. ↩︎

- I argue the Guidonian Hand may be considered as an interface adjacent to the monochord, keyboard, and the fusion of the two: the keyed monochord. As Roger Moseley explains, “Pythagorean geometry is analogized, arithmetically seriated, and thus rendered digitally manipulable” in keyed monochords, which allows them to “physically perform the Guidonian mapping of the string’s ratios.” Moseley, Keys to Play: Music as a Ludic Medium from Apollo to Nintendo (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016): 80–81. ↩︎

- Shigehisa Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine (New York: Zone Books, 1999), 8. ↩︎

- Applicants at a rigorous audition in 1604 for the choirmaster’s position at Toledo Cathedral were tested for the ability to, “upon a mensual music part, indicate two voices on the hand [i.e. show two new parts with two hands using the method of the Guidonian Hand] while singing another.” (“Sobre una voz de canto de organo, puntar dos vozes por la mano y cantar una.”) Philippe Canguilhem, “Singing Upon the Book According to Vicente Lusitano,” Early Music History 30 (2011): 92. See Appendix, “The Twenty Tests for Applicants for the Post of Choirmaster at Toledo Cathedral in 1604,” 103–4. See also Elam Rotem’s excellent video essay, “Solmization and the Guidonian Hand in the 16th Century,” https://youtu.be/IRDDT1uSrd0?t=694, 11:36–12:50. ↩︎