[…] Continuation of Part I […]

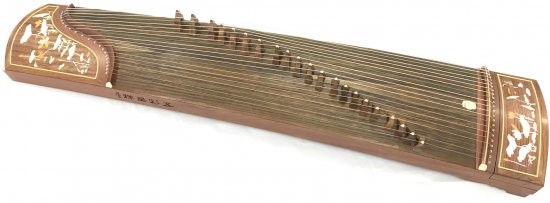

I ended the previous post leaving open a question about the Kinkafu’s name. Let’s contemplate the first character in the title of the manuscript (Kinkafu 琴歌譜, qín + songs + notation, i.e “notation of qín songs”). The character 琴 is the same character that is used in the Kojiki to represent the instrument that Emperor Chūai is being urged to play in the quote with which I began, and which I have earlier broadly identified as a zither. This character originally indicated a specific Chinese zither with seven strings, long held to be the most refined.[1] But because the Kinkafu’s notation is for a six-stringed instrument, we know that it could not have been for the Chinese qín, and was more likely for the wagon (和琴),[2] a six-stringed zither whose name quite literally means “Japanese qín.” Despite having such a name, however, it is quite unlike the original qín in one important way. See figs. 4–7 for a comparison of four East Asian zithers:

Unlike the qín after which it is named, but like the zhēng after which it is not named, the wagon has movable bridges. But unlike the zhēng, and the koto directly descended from it, the wagon’s bridges are customarily placed in a zigzag pattern, creating strings of alternating lowness and highness, rather than the low-to-high pattern seen in the other instruments, and common also to Western stringed instruments. This zigzag pattern sets the wagon quite apart from any Chinese instrument—it marks the instrument, and by extension the Kinkafu’s settings of songs from the Kojiki and other similar sources, as determinedly native, a product of the native Japanese mind as opposed to anything imported from the continent (at least in substantial part). In both the Kojiki and the Kinkafu, the use of Chinese characters phonetically, rather than semantically, to write out these songs accomplishes the same thing—it suggests that the sounds of the original language are what matters most, and that the semantic power that these characters have should be intentionally bypassed.

And yet, despite these gestures towards accenting native Japanese music and language, all of it is carried out in Chinese trappings, and depends on them for legitimacy. In much the same way that a wide variety of Western European cultures long used Latin for much if not all of their high-prestige writing, classical Chinese served much the same purpose in a wide variety of East Asian cultures. In both cases, this high-prestige status of the classical language extended far beyond the language itself, just as the Greek-temple-styled United States Supreme Court building and the fasces on the Norwegian and Swedish police forces’ coats of arms make evident that classical Greece and Rome have never lost their high-prestige status in the Western world. Likewise, classical Chinese symbology remains all over East Asia, and when the Kinkafu was being written, this was still rather a novelty for Japan. While there is nothing unusual in importing a writing system, the way this period of Japan idolized Chinese culture goes far beyond script importation—Japan had already had music, gods, and something of a hierarchical government structure before importing Chinese versions of the same (or Indian, routed through China, in the case of the gods). Thus in the Kinkafu we can see the same spirit at work in calling the wagon by the name of 琴 (qín or, in Japanese, kin), despite the great differences between the wagon and the Chinese qín. The implication may be that the wagon deserved just as much prestige as the qín did, though this could be asserted only by calling it a qín.

Returning to the Kojiki tale about Emperor Chūai and his zither, what specific instrument might be meant by 琴 here? It could be that the character 琴was used simply because the authors could think of no other way to represent some plucked string instrument. It is unclear how many grains of truth lie behind this tale, but still, the image that is called to mind by the passage is of a Chinese-style emperor playing a Chinese qín many centuries before any Chinese culture had been imported to Japan. The writer harnessed the prestige of such symbols with the aim of transferring that very prestige to its narration—even though the Kojiki, in the estimation of scholars like Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801), transmits elements of the pre-Chinese native Japanese tradition more purely than does the Chinese-aspiring Nihon Shoki.[3] The native had to be wrapped in the foreign in order for its nativeness to be preserved and displayed.

[1] Unlike its cousin the zhēng (箏), it was never fully imported and naturalized into a Japanese instrument—the instrument that Japanese people call koto is descended from the zhēng rather than from the qín, despite being written with either the 琴 or 箏 characters.

[2] Brannen 275.

[3] Philippi 32.

[…] Continuation: Part III […]