恐。我天皇、猶阿蘓婆勢其太御琴。

自阿至勢以音。

I am afraid. My emperor, play the great honored zither now.

From 阿 to 勢 in accordance with their sounds.

The above utterance looks like Chinese—and in fact, most of it is. But what of the footnote in small type after the main text? It says that the characters 阿蘓婆勢 are to be read phonetically, which is to say they are not to be read for their meaning. 阿蘓婆勢 is not a Chinese word—it in fact phonetically represents the Old Japanese word asobase, quite literally “play” (in the imperative). This statement of fear, urging the emperor to play his zither (qín), comes from the Kojiki 古事記, Japan’s oldest extant work of literature, completed in 712 CE, which compiles myths, legends, and some actual history of early Japan into a mostly-seamless three-volume whole. It begins with the separation of heaven from earth as the first gods are born and ends with the reign of Empress Suiko at the turn of the seventh century. The above quote, ascribed to the long-lived courtier Takenouchi no Sukune, occurs during what ends up being the death scene of Emperor Chūai, which canonically occurs in 200 CE.[1] The emperor has been ordered by a god to cross the sea and conquer the supposedly treasure-filled Korean kingdom of Shilla. As the emperor doubts the god’s word and is reluctant to carry out the task, the god threatens him. This is where Takenouchi expresses his fear, and asks the emperor to play the zither, which he does. But it is to no avail—a moment later, the emperor has been struck dead.

The apparently magical properties of the zither (qín) as narrated in the Kojiki, however, is not my focus here. Rather, I want to focus on what specific instrument the word qín indicates in this context. I have primarily translated the word qín as “zither” because it is a broad organological category. By zither I mean a stringed instrumentin which the strings are stretched across an oblong, flat wooden body. I use this general word because while the word qín originally referred only to a specific ancient Chinese zither, that instrument’s high prestige led the word qín to be applied to other zithers in other places as well. Thus we do not always know specifically which instrument qín may have been referring to in Japanese texts like the ones in question: qín could indicate different zithers in different contexts. Moreover, I aim to draw attention to the medium through which the Japanese tale of the zither is told, namely a mixture of classical Chinese, written with Chinese characters functioning logographically, in Chinese syntax; and some words and phrases in vernacular Japanese, written with Chinese characters functioning phonetically (like 阿蘓婆勢 for asobase, “play”). This mixture of languages and modes of inscription is not entirely unique to the Kojiki, though other texts that deal with it do it differently—it is clear that the Kojiki was written in a time when the whole notion of writing in Japanese was still being thought out. Like the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki (“Chronicles of Japan,” 720 CE), also contains many phonetically-written songs and the songs in these two chronicle documents preserve Old Japanese phonetics and syntax better than almost any other source.[2] It is unclear exactly how musical all of these songs (歌) were originally meant to be—the line between “song” and “poem” often seems more or less nonexistent at this time. But what is relevant to our discussion here is that a few centuries later, specifically in 981 CE, several of the songs from the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki were preserved in music notation in the Kinkafu 琴歌譜 (literally “notation of zither songs”), one of the oldest extant examples of music notation to come out of Japan. It is not entirely clear if the melodies encoded in the Kinkafu were newly-composed late-tenth-century ones or whether they were transcriptions of a longer oral tradition. It is also not entirely clear even today how these melodies would have sounded—the specific type of notation used is not attested adequately in other sources—and the document’s brief preface does not explain how the instrument is tuned. What the Kinkafu does show us, however, is how a culture eager to define itself can find that work almost impossible without relying heavily on the culture it is trying to distance itself from—in this case, we see how Japan, in producing a body of artworks that is meant to be clearly Japanese and not Chinese, still must do so through Chinese symbology.

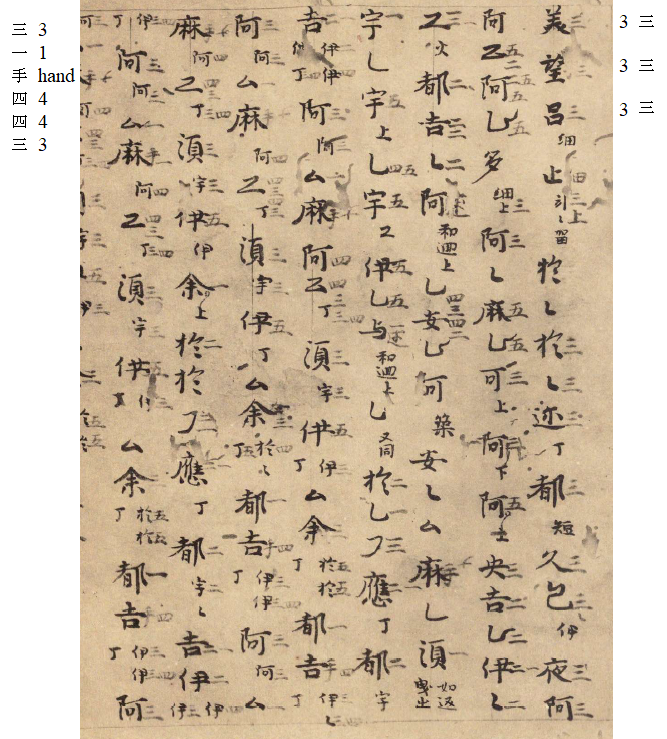

What the preface does make clear, however (see fig. 1), is that the notation is a tablature, with numerals corresponding to the strings of the zither, as well as the character for hand (手), whose function remains uncertain, though the early-twentieth-century scholar Tsuchida Kyōson conjectured that it might be a sign calling for a percussion instrument to be played.[3] The syllables to be sung are sometimes elongated with repeated characters of the requisite vowel sound, producing a striking and rare representation of a melisma or long-held note. For example:

蘇於於於於良阿阿阿阿

so o o o o ra a a a a

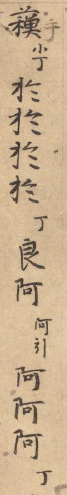

These ten characters, which begin a New-Year’s song in the Kinkafu attributed to Emperor Keikō (r. 71 – 130 CE, according to the Nihon Shoki) spell out through phonetic Chinese characters what is ordinarily only a two-syllable word in Japanese, sora for “sky.” The vowel-extending characters 於 and 阿 also do more than simply show a rough approximation of how long to hold each vowel: they also allow for what look to be precise performance instructions to be given about the melisma. After all, what it really looks like is what you see in fig. 2:

Again, while we cannot know for certain exactly what these subscript characters mean, 小丁 suggests smallness and reticence of some kind, while 阿引 literally means “pull on the ‘a’ sound,” suggesting perhaps that a growth in the strength of the “a” sound, greater than that of the “o” sound may be called for two-fifths of the way into it (i.e. after 良阿, before 阿阿阿). This gives us a tantalizingly incomplete glimpse into the way these moments might have sounded, suggesting a notation of the dimension of time in which differences in inflection may have mattered. They also show us the process of trying to wrangle a notation system for an apparently native singing tradition entirely out of imported Chinese graphemes. It is also possible that there is more Chinese influence in the singing style by this point than the source material lets on, but that does not at least seem to be the image it is trying to project: all of the words in the poems and their metric styles are of native origin, and their source material is mostly Japanese history books written to project the notion of Japan as its own nation.

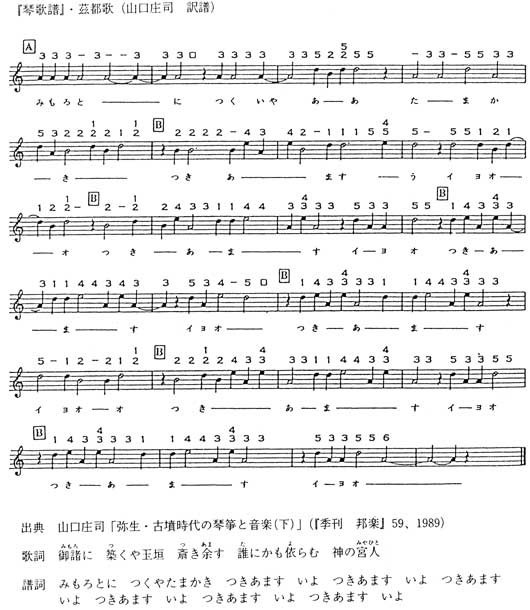

As far as the pitch content itself goes, there have been conjectures by modern scholars. In 1988, based on a close reading of the Kinkafu’s preface and comparisons to the tunings of other instruments, Yamaguchi Shōji proposed a tuning of the six strings of the zither to only four pitches, and has realized that tuning in the following transcription for the first song in the Kinkafu (the same one represented in fig. 1, if one wishes to compare), tuning it A4-D5-E5-A4-B4-D5:[4]

If this is correct, the song and others like it are made entirely out of the pitches A-B-D-E within a single octave, a constraint of pitch materials that is consistent with much other Japanese folk music.[6] The lack of any note a third above the A final is also consistent with a great amount of Japanese music, as suggested by Uehara Rokushirō’s 1895 theory of an in and yō modal binary for Japanese vernacular song.[7] But since we cannot know its tuning for certain, we have to look elsewhere for what this notational document may have meant to its creators and users. For example, the first character of the manuscript’s name (琴) connects to a dense network of meanings that can help to contextualize both the Kinkafu and the zither scene in the Kojiki. I will turn to this character and its network of meanings in the next installment of this post. I will turn to this character and its network of meanings in the next installment of this post.

[1] This date is according to the famously unreliable chronology of the Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (“Chronicles of Japan”), which was finished in 720 CE and tells many of the same stories as those in the Kojiki, though it does not include this zither episode. Unlike the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki is written in the format of Chinese historical annals like the Spring and Autumn Annals and Records of the Grand Historian. This has a great deal to do with why it, and not the Kojiki, was for most of Japan’s history considered the official, canonical account of Japan’s early history. The exaggerated lifespans of its early emperors have been called into question only since the twentieth century.

[2] For this reason, these songs were the places to which nativist scholars like Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) could most profitably look when they wanted what felt like authentic snapshots of something resembling a “pure Japanese” ancient tradition.

[3] Tsuchida, via Masuda.

[4] Yamaguchi, via Masuda.

[5] In Masuda.

[6] Koizumi 95.

[7] Uehara’s theory has been rightly questioned and refined by Koizumi 1958 and Makino 1961, but enough of it is still generally accepted that the thirdlessness of many Japanese scales remains safe to assert.

[…] Continuation: Part II […]