“Hah!

It’s poetry in motion

She turned her tender eyes to me

As deep as any ocean

As sweet as any harmony

Mmm – but she blinded me with science

‘She blinded me with science!’

And failed me in biology

Yeah-eah!”

–Thomas Dolby, “She Blinded Me With Science”

Before Thomas Dolby released the song “She Blinded Me With Science” (1982), he knew that to make a song climb the billboard charts, it helped to have a music video on MTV. Dolby thought up a music video concept and pitched it to his producers first, then wrote a dance track to go with it. The strategy worked. A few years later, Dolby and collaborators created another set of viral hits: a file format called Rich Music Format (RMF), followed by a plugin called Beatnik which enabled users to create original music (Herring 2014). The Beatnik plugin soon became a cornerstone of early Internet music theory culture, as programmers used it to create a wide range of music theory learning programs that could be distributed over computer networks in the 1980s and ‘90s.

In this blogpost, I describe how North American music theorists in the 1970s-90s were “blinded by science” during the Internet revolution, which both disconnected them from many humanities fields as well as afforded them material and social benefits. This relatively early investment in the Internet from music theorists led to a rise in perceived scholarly legitimacy and a steady increase of institutional support for “music theory” as a position and an activity. This blogpost is a companion to my recent chapter “Music Theory and Social Media” (2022), which offered an overview of “music theory” as it circulates on platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and Reddit. There my focus was recent (post-2000) examples of music theory online, such as discussion groups, trends, memes, and clickbait. Here I discuss an earlier era of music theory on the English-language Internet, pre-2000.

The social media music theorists of today, whether they know it or not, are building on a lineage of Internet music theorists going back at least to the 1970s. Early Internet music theorists used their own version of Dolby’s prescient pop strategy; they adopted new media in its nascent state to create viral music theoretical tools that built the foundation for social media music theorists with millions of clicks and views in 2022.

Digging into archives, interviews, digital media histories, and a range of online material, I map some of the sources that would constitute a history of music theory on the Internet. These include the first music theory lessons transmitted via networked computing, interactive websites, email lists, and electronic journals.

Music Theory and the Proto-Internet

The Internet is a confluence of technology and human influence, of inclusions and exclusions—a constantly shifting network of people and things. The term “Internet” was first used in a computer program report in 1974 as a shorthand for Internetwork (Cerf et Al. 1974).[i] The origins of networked computing (“the Internet”), however, are not traceable to any particular person or invention, rather to a series of interrelated happenings and to relationships between technologies, people, and organizations. Histories of the Internet often wrongly imply that predecessor networks were built primarily for government purposes. The case of music theory demonstrates why such an implication is misleading. While some parts of early networked computing were tied to government agencies such as the U.S. Department of Defense, others were not. One such example was the PLATO system, an emergent computer network which began at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UI), and spread to other learning institutions in the 1970s-1990s.[ii]

Some of the first online music theorists were those who created music theory software for PLATO or were schooled by the PLATO system. PLATO’s instruction materials covered a range of subjects, from elementary math to university-level chemistry and, starting in 1970, music and music theory (Dear 2017, 175-191).[iii] PLATO was also a cornerstone in the history of cyberculture, being a testing ground and fountainhead for a range of significant cyberculture concepts, including message boards, forums, emailing, direct messaging, picture-based languages (the first digital emojis were created on PLATO IV in 1972 by Bruce Parello, a UI student), remote screen sharing, and interactive gaming.

A team at the UI School of Music, led by G. David Peters, worked from 1970-1994 on a PLATO-delivered system of online music instruction. PLATO had a voice synthesizer called Votrax and a synthetic woodwind instrument called the Gooch Synthetic Woodwind, named after inventor Sherwin Gooch (later renamed the Gooch Cybernetic Synthesizer). Its music theory lessons were similar to flashcards, with questions such as “What note is a major third above G?”

PLATO’s music instruction materials were tested by dozens of UI professors in their music theory courses (Dear 2017, 186-7). Later they were adopted by other institutions, such as University of Delaware, University of Hawaii, and Indiana University. Delaware acquired PLATO terminals in the 1970s, including the music lessons called GUIDO.[iv] Hawaii gained telephone access to four ports on the University of Illinois’ PLATO System in May 1977.[v] Indiana adopted in the 1980s the PLATO system of music dictation drills, keyboard lessons, ear training, composition instruction, and theory exercises. A version of PLATO was created for Apple II in the 1980s, leading to more widespread usage of the system, and a larger platform for testing different kinds of music lessons.

Music Theory Online: The First Music Theory E-Journal

As computer networking became more widespread in the 1980s, researchers in a range of mostly-STEM fields began experimenting with digital publishing. By 1990, major scientific organizations were embracing the idea that e-journals could compete with traditional print journals. The hope for these e-journals was that they would initiate a major shift in the nature of scholarly communication. Patricia A. Morgan, director of publications for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, put it this way: “It’s a race. We want to be first” (Wilson, 1991).

Music theorists also strived to win “the race.” Members of the newly-formed Society for Music Theory (SMT) were interested in developing music theory publications to help legitimize the society. As a handful of academic theorists were tuned to happenings in STEM fields, they began to float the idea of an electronic journal.

Their e-journal would need a digital distribution method. Other e-journals were distributed through email lists—something the SMT had in “smt-list”, the list-serv created in 1990-1991 by Lee Rothfarb and Jane Clendinning.[vi] Rothfarb took the lead, going to the UNIX administrator at Harvard, Tom Heft, with a “cool idea” for an online music theory magazine. Heft was enthusiastic and helped Rothfarb with programming exercises in exchange for music theory help on bass guitar.[vii]

Music Theory Online (MTO) published its first essay, “Schoenberg at the Movies: Dodecaphony and Film” by David Neumeyer, in February 1993. The SMT Executive Board voted to make MTO an official SMT journal in 1994. When Rothfarb moved from Harvard to Santa Barbara in 1994, he moved the entire operating system with him and stayed with MTO until 1999, when he became department chair and handed off journal leadership.[viii]

Experimental Music Theory Projects on the Early Internet, 1980s-1990s

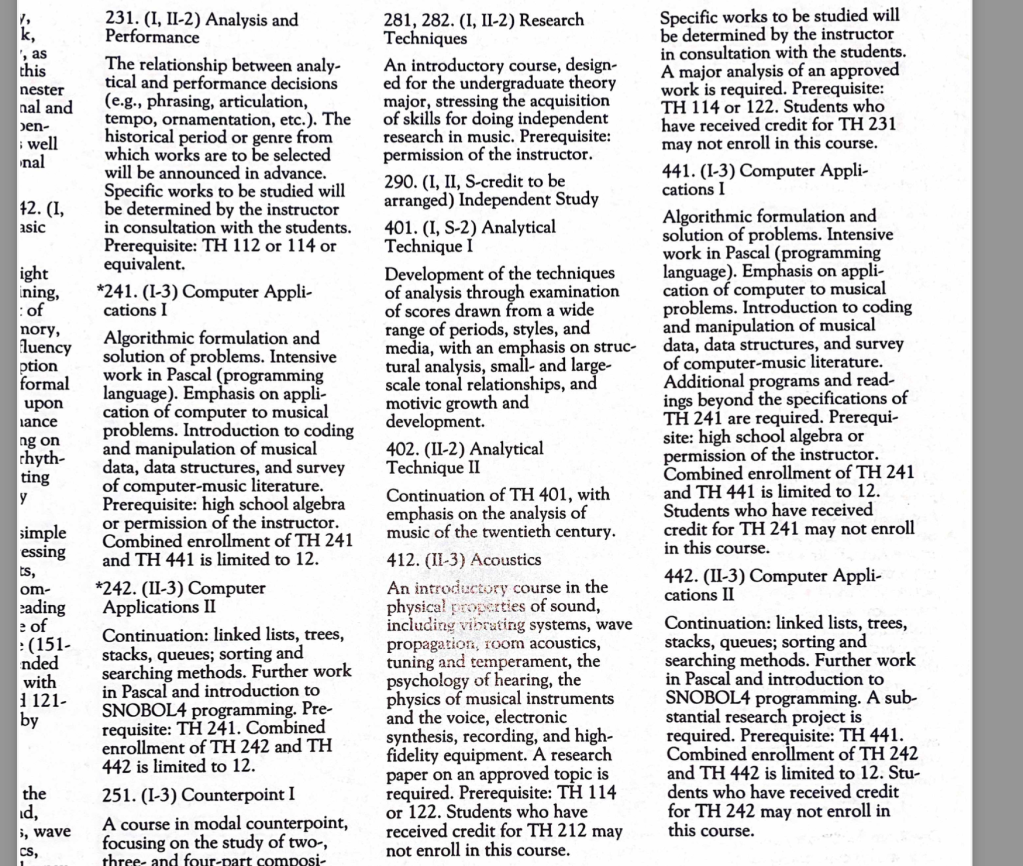

In the 1980s, the Internet became a testing ground for a range of different kinds of music theory projects. College courses that taught programming skills to musicians began to emerge, such as those created by Elizabeth Marvin and Aleck Brinkman.[ix] As personal computing became more feasible, followed by home Internet access, users used the net to create their own music theory content such as original websites, software, and plugins. Some formed communities on bulletin boards or forums. Others took on teaching roles through web portals such as America Online (AOL).

Poundie Burstein began using the online portal AOL in 1991 after starting a faculty job in music theory. He received an email from AOL inviting him to be a music theory tutor in exchange for free AOL access, and signed up. Over time, more tutors joined in, which led to more attention—and more problems. There was no system for moderation, and no way to organize content or handle problematic messages. Trolls and spam flooded the site and eventually it was abandoned.[x]

Individual creators avoided spam death by staying off of major platforms, such as the programmers who made and distributed their own music theory software online. Keith Kothman, a faculty member at the University of Miami in the 1990s, was one. Kothman came across the Beatnik plugin in 1998, which came with a downloadable set of General MIDI sounds that could be controlled via JavaScript (JS).

“I used it to program intervals and chords as objects, with built-in context for practice and clues,” Kothman recalls. “For example, a m7 wants to resolve to a 3rd, like in V7 – I. With Beatnik, I could play individual tones with JS code, embedded in the web page.”[xi]

Several hundred miles away, Lee Azzarello was a student at Antioch College in Ohio, using campus Internet service to organize discussions around the music programming language SuperCollider.[xii] On the now-defunct platform Hotline, Azzarello created the group “Falling Forward,” named after a hardcore punk band from Louisville, which attracted people interested in techno music, “glitch” computer art, outsider music theory, and algorithmic composition. This group continued on after Azzarello turned to other projects and continued to exist until the demise of the Hotline platform.

More music theory websites flourished in the late 1990s. José Rodriguez Alvira launched the interactive website teoria.com in 1997, as a complement to his music theory courses at the Conservatory of Music of Puerto Rico. musictheory.net was launched in 2000 with lessons, exercises, and different kinds of music theory calculators. In 2005, Timothy Cutler and Patricia Gray created the first Internet database of music theory examples, entitled musictheoryexamples.com. Cutler and Gray regularly receive fan mail from users based in North America, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, Israel/Palestine, Great Britain, and Australia.[xiii] These are just a few examples of the online world of music theory as it was emerging.

Concluding Thoughts: What Can Music Theory Do Online?

Newer Internet users may not remember a time when emailing, web browsers, bulletin boards, and online journals were truly novel, nor may they think to question the existence of networked computing, online music theory conferences, or participatory musical activities on the Internet—what Paula Harper (2019) has called “viral musicking.” Even scholars occasionally misinterpret the status of the Internet, presuming it to be perfectly global, available to everyone, representative of the human population, or a stable ground of meaning. One of the paradoxes of the Internet is that it is at once a top-down organized system and a user-generated one, and this is true at many different scales.

Observing rarified corners of Internet history, such as the music theory corners, can be a way of recognizing and contemplating such paradoxes. The Internet and the Society for Music Theory (SMT) both emerged around the same time. Given the connection between the early Internet and the Society for Music Theory (SMT), my research suggests that internet-generated discourse has contributed in shaping North American music theoretical discourse writ large. Members of the SMT had no special talent for computing, yet they made extensive use of computer networking long before most other humanities fields thought to do so. They created email lists and e-journals, and kept them active for decades. The SMT’s successful use of the early Internet had rippling effects on the meanings and uses of “music theory” in the United States, and globally. Since the formation of the SMT, similar societies have formed in France, Belgium, Italy, Croatia, the Netherlands, Germany, South Korea, and Russia. Hiring patterns in North American higher education have changed: Prior to the late 1970s, music theory was mainly taught by composers, performers, or musicologists. The SMT promoted the idea that music theory should be taught by professional music theorists.[xiv] This effort to create careers and publishing opportunities for theorists has been well-documented, yet the significance of the Internet to these advocacy goals remains under-researched.

“Music theory” is a multi-faceted and ever-changing discursive object online, bound up with complex and often contradictory logics propagated by software designers, academics, entrepreneurialism, piracy, individual user preference, algorithmic operations, and what Shoshana Zuboff (2019) calls Surveillance Capitalism—an Internet-enabled economic order in which user data is harvested for profit—all of which affects music theory beyond the net in turn. In other words, the Internet has become a significant site for music theory, which is affecting how music theory is being conceived beyond the Internet, even and perhaps especially when the Internet appears to be a mere tool for networking.

In 2022, music theory does not look like academic music theory for most people. It looks like conversations on Reddit; online “think pieces” about popular songs, artists, and trends; video essays by online creators. Academic music theorists have much to learn by acknowledging that the history of music theory is partially being written by people who are not within the academic realm. The Internet is another place for people to reinvent continuously what music theory can be: it might be an approach to fundamentals, a strictly intellectual enterprise, an embodied practice, a songwriting method, a way of communicating about sound, or something else entirely.

Brinkman, Aleck R. and Elizabeth W. Marvin. 1996. “CD-ROMs, HyperCard, and the Theory Curriculum: A Retrospective Review.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 10: 91-188.

Cerf, Vinton, Yogen Dalal, and Carl Sunshine. 1974. “Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program.” https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc675.

Dolby, Thomas. 1982. “She Blinded Me With Science.” U.K./U.S.: Capitol Records.

Doornbusch, Paul. 2017. “Early Computer Music Experiments in Australia and England.” Organized Sound, 22.2: 297-307.

Ewell, Philip A. 2020. “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame.” Music Theory Online, 26.2: https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.2/mto.20.26.2.ewell.html

Harper, Paula. 2019. “Unmute This: Circulation, Sociality, and Sound in Viral Media.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

Herring, Angela. 2014. “He Blinded Me With Non-Linear Music Theory.” News@Northeastern: https://news.northeastern.edu/2014/02/03/he-blinded-me-with-non-linear-music-theory/

Hisama, Ellie. 2021. “Getting to Count.” Music Theory Spectrum, 43.2: 349-363.

Krol, Ed. 1994. The Whole Internet. 2nd Edition. California: O’Reilly and Associates.

Neumeyer, David. 1993. “Schoenberg at the Movies: Dodecaphony and Film.” Music Theory Online, 0.1: https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.93.0.1/mto.93.0.1.neumeyer.html.

McCreless, Patrick. 2010. “Society for Music Theory,” Grove Music Online: https://doi-org.silk.library.umass.edu/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2088229.

Malin, Yonatan, ed. 2014. “History and Future of MTO.” Music Theory Online, 20.1: https://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.1/toc.20.1.html.

Piilonen, Miriam. 2022. “Music Theory and Social Media.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Music Theory. Oxford Handbooks Online.

Rothfarb, Lee. 2014. “History and Future of MTO: Early History.” Music Theory Online, 20.1: https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.1/mto.14.20.1.rothfarb.html.

Wilson, David. 1991. “Testing Time for Electronic Journals.” The Chronicle of Higher Education: https://www.chronicle.com/article/testing-time-for-electronic-journals/?cid2=gen_login_refresh&cid=gen_sign_in.

Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. New York: Public Affairs.

[i] For an introduction to early networked computing, see Krol, 1994. For reflections on the first computers that could reproduce sounds, see Doornbusch (2017).

[ii] PLATO stands for Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations and was the first generalized computer-assisted instruction system (CAI), that is, lessons taught by a computer. Brian Dear. 2017. The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the PLATO System and the Dawn of Cyberculture. New York: Pantheon Books.

[iii] Thanks to Robert Gjerdingen for the tip, in conversation April 2022.

[iv] Dear, Friendly Orange Glow, 352.

[v] The UH Statistical and Computing Center opened in 1960, running the operating system IBM 650. There were ten users. By 1970, the Center’s user-base had increased to 2000. UH acquired PLATO ports in 1977 and it became an official instructional system in 1980. See the UH Data Comm Timeline, https://net.its.hawaii.edu/history/timeline.html.

[vi] What follows is an abbreviated account of smt-list. In the late-1980s, Lee Rothfarb and Jane Clendinning heard from colleagues in the sciences about lists of email addresses that connected researchers within a field. In 1990, at the SMT meeting in Oakland, Rothfarb and Clendinning set up a table with a yellow legal pad to collect email addresses for what would become the first email directory for theorists. Clendinning took the list home, typed it up, and emailed it as a text-only file to Rothfarb, who took it to the Harvard Science Center Computer Administration which was next door to the music building. Together they created the text-only mailing list “smt-list” (later “smt-talk”). This was used to messages, follow discussions, and create sublists on a range of topics (e.g., set theory, tonal harmony). Eventually they found a method to archive the texts, so people could read back through old threads. For further reading, see Rothfarb (2014). See also the SMT archived newsletters from the 1990s: https://societymusictheory.org/archives/newsletters.

[vii] Lee Rothfarb in conversation with the author, April 2022.

[viii] For further reading about MTO, see the 2014 colloquy, “History and Future of MTO.”

[ix] Elizabeth Marvin in conversation with the author, June 2022. See also Brinkman & Marvin (1996).

[x] Poundie Burstein in conversation with the author, April 2022.

[xi] Keith Kothman in conversation with the author, April-June 2022.

[xii] The SuperColider website remains preserved in its early form at http://audiosynth.com/.

[xiii] Timothy Cutler in conversation with the author, April 2022. I thank Timothy Cutler for sharing examples of correspondence from the places mentioned.

[xiv] For extended discussions of SMT, see Ewell (2020), Hisama (2021), McCreless (2010).