Part II. The Musurgia universalis in New Spain

[…] Continuation of Part I. Musicosmopolitics […]

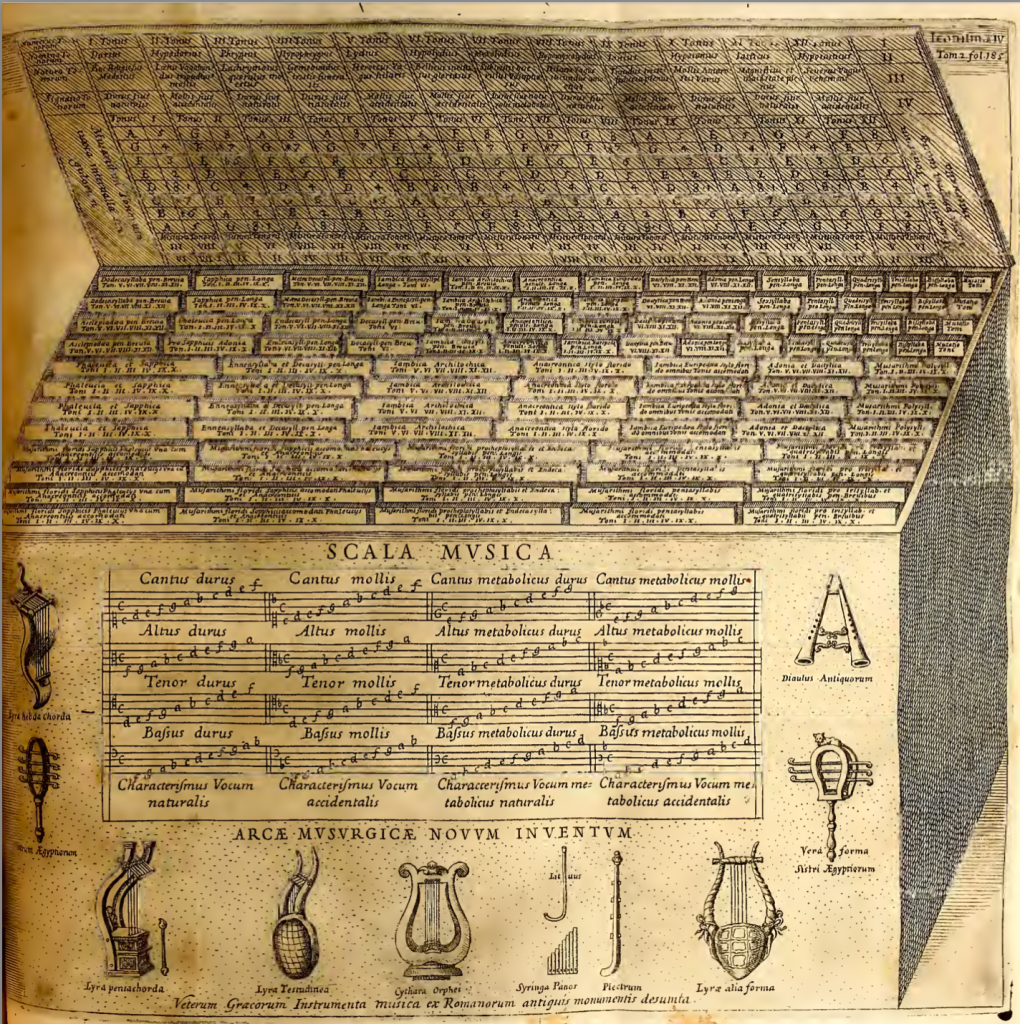

The first copy of the Musurgia universalis (1650) found in New Spain arrived by way of Father François Guillot, a former colleague of Kircher’s at Avignon who had been living in Puebla since 1635 with the Spanish name of Francisco Ximénez (Osorio Romero 1993, xvii). Upon finding one of Kircher’s books, Ximénez ordered from Seville as many of Kircher’s works as could be found in the city. He then gave a copy of the Musurgia to Alexandro Favián—a criollo priest with polymath ambitions that rivalled Kircher’s own. As he writes in the first of many letters to Kircher, Favián built a lyre based on the scant bibliography. But the criollo scientist was unsure if “it conformed to those employed nowadays in your countries, which are the perfect ones.” One day, he relates, “the admirable Musurgia by Your Reverence arrived in this Kingdom, in which I have seen that [the lyre] I made was in all conformity with everything that Your Reverence teaches.”[1] Even if Favián judged it to be “harmonically correct” (which he was more than qualified to do), his criollo lyre still required authorization according to the standards of the center. Under the global design shared by Kircher and Favián, episteme trumps aesthesis.

Favián sent money and specimens for Kircher’s famous museum and built a Kircherian library in Puebla complete with a framed portrait of the Jesuit. In turn, Kircher ended up dedicating his 1667 Magneticum Naturae Regnum to Favián, but not before confirming that the criollo had Italian ancestry:

I admired your multiple studies and the cultivation of all the fine arts in you, a native of the New World; yet, that in those foreign regions of America, in those parts of the heavens unknown to us, a man equipped with such aids of virtue and gifted by God’s prerogative with so many charismas could be found, I could not persuade myself of. Finally, through reciprocal epistolary exchange over some years, having dissipated all doubts, I learned that you were not of Indian origin but of the Illustrious Family of the Fabians from Genoa—higher than any exceptions—of stock inserted into Spanish lineage (Kircher 1667, 5-6).[2]

Renowned for his credulity, Kircher could only believe in a polymath if he was not native, but a transplanted European—if he was Kircher’s equal.[3] The asymmetry between Favián and Kircher clearly illustrates the ambiguous position criollo intellectuals occupied in the global Republic of Letters. Alienated from the Indigenous world by reason of their settler position, criollos were also marginal to those of the metropolis, who did not recognize them as equals because their “mixed blood”—a result of rape and forced marriage of Indigenous women with Spaniards—marked them as intellectually and ontologically inferior to white Europeans (Bauer and Mazzotti 2012). From this position, they had few choices but to reproduce the same global designs that marked them as exterior to the epistemic and cultural centers.

Perhaps no one was more aware of the conflicting body-political demands of the global design than Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, another criolla whose racial otherness was re-marked by her gender (Martínez-San Miguel 2017, 15). Yet, while Sor Juana explicitly questioned the idea that femininity—for her, the exterior difference of an otherwise genderless soul—was a hindrance to intellectual accomplishment, her broader output was nevertheless aligned with the Catholic global design where, as Yolanda Martínez San Miguel puts it, “the argument of human equality among criollos and Europeans is developed to further incorporate the Americas into Catholic religion and the western episteme” (Martínez-San Miguel 2017, 15). A voracious reader, Sor Juana’s fascination with Kircher is well attested in her works and in a well-known portrait by Juan de la Miranda and its copy by Miguel Cabrera, both of which place volumes titled Kirkerii opera among the philosophical and theological works in her famous library (Paz 1982, 309; Lyon 2017). She summed up her enjoyment of Kircher’s book with the playful neologism “to Kirkerize” (kirquerizar), which an early scholar glossed as “to imitate the famous mathematician of her time, Athanasius Kircher” (de la Maza 1952, 18)(Findlen 2004, 333). Her most celebrated poem, Primero sueño, is a metaphysical out-of-body reflection on the structure of the cosmos inspired more by Kircher’s Itinerarium extaticum (1656) than by Plato’s “Myth of Er.”

Sor Juana was also a musician. In a 1688 poem dedicated to her former patron and Sapphic love object, the vicereine of New Spain María Luisa Manríquez de Lara y Gonzaga, Countess of Paredes, Sor Juana promises a music treatise where she would “reduce for easier handling” all the musical rules (Cruz 2009).[4] The most intriguing claim of the nonextant treatise is expressed in its very title, Caracol (Conch Shell). Since, as she writes in the poem,

En él, si mal no me acuerdo,

me parece que decía

que es una línea espiral,

no un círculo, la armonía;

y por razón de su forma

revuelta sobre sí misma,

le intitulé Caracol,

porque esa revuelta hacía.

(Romance 21, vv. 116-128).

[In it, if I am not mistaken, I believe I said that harmony is a spiral line, not a circle. And because of its shape, turning around itself, I titled it Conch Shell, because of the turn it made.]

The precise meaning behind the intriguing notion of a spiral harmony remains a mystery. But it cannot refer to the lack of closure of the circle of fifths in Pythagorean tuning, as Robert Stevenson (1996) and, more recently, Mario Ortiz (2007) have argued, not least because the very notion of a closed circle of fifths and hence the condition to figure this excess as a spiral did not emerge until at least 1711 with Heinichen’s Neu erfundene und grundliche Anweisung . . . des General-Basses (Barnett 2002, 444; Lester 1989, 110-112).

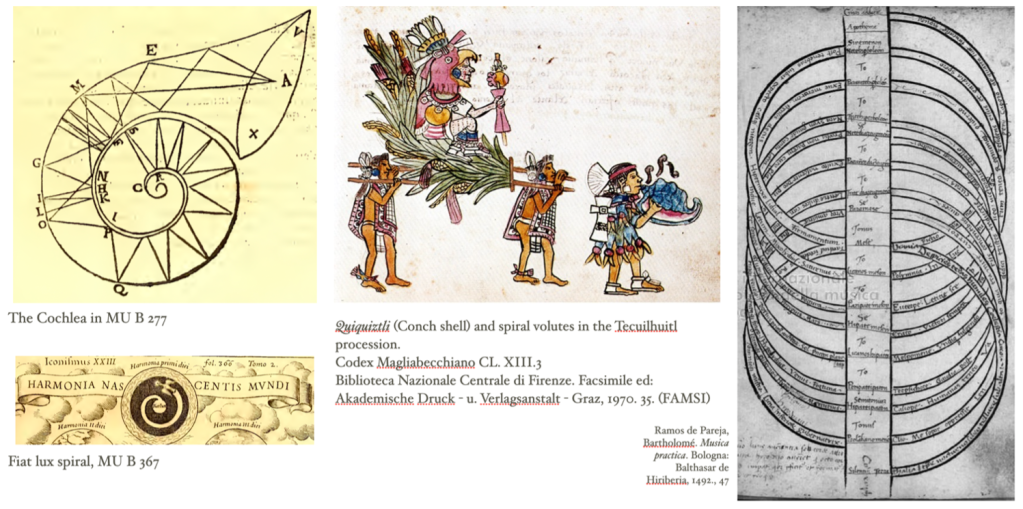

The notion of “a spiral harmony” is more capacious, and likely cannot be circumscribed by a single paradigm. Sor Juana had a wealth of both spiral and circular images to engage: from the various spiral-shaped objects in Kircher’s Musurgia, which she obviously knew, to the (less likely) spiral in Bartholomé Ramos de Pareja’s 1482 Musica practica, as suggested respectively by Octavio Paz (1982, 316-17) and Rocío Olivares Zorrilla (2015). As Stevenson suggests, she must have also been familiar with the Aztec conch shell or quiquiztli and the spiral volutes that serve as the metonymic glyph for cuicatl or “song,” although nothing else in the poem suggests she was directly drawing on Indigenous elements to contest hegemonic notions of harmony (Stevenson 1996, 13; Finley 2014, 31).[5]

Less a contestation of the hegemony of the circle or its decentering (as in the ellipse analyzed by Cuban poet Severo Sarduy), the spiral is an affirmation of the center from the periphery, a tendency towards a center that is only reached by augmenting the distance from the origin (Sarduy 2013, 208). The spiral is thus an evocative baroque figuration of the position that criollo intellectuals like Favián and Sor Juana occupied with respect to the hegemonic (if idiosyncratic) discourse deployed by Kircher. The diversity of the body-politics of the Jesuit’s readership was thus caught in the darker side of the movement’s mission, a global (i.e., colonial) project of universalist ambition so successful that it almost engulfed its readers. Remarking their trace in the musicological canon is the task of the global musicologies of today.

Coda

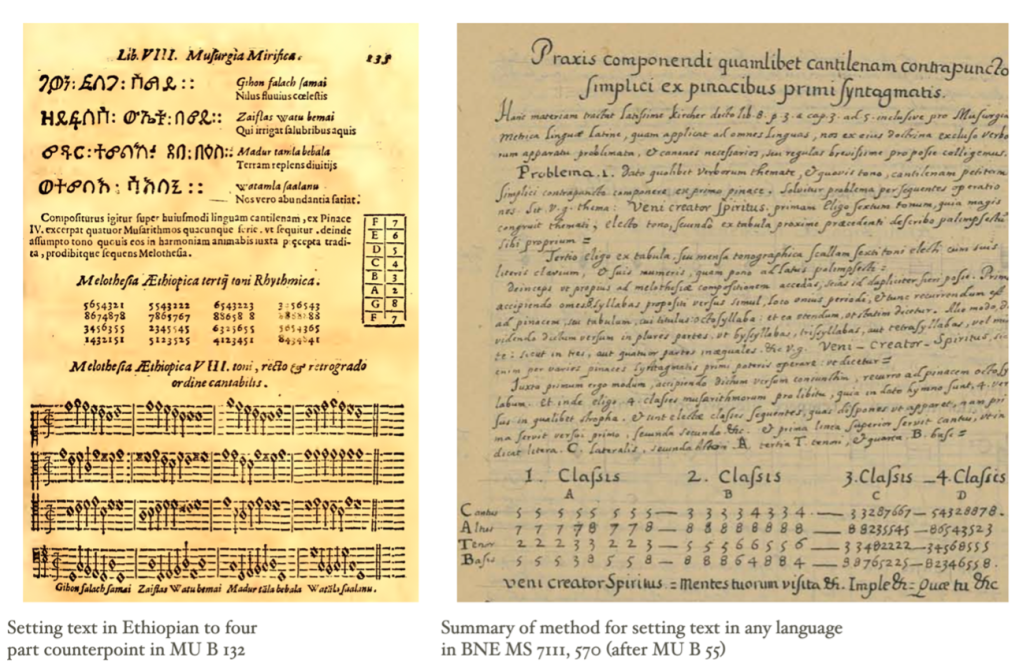

The most immediately “colonial” element in the Musurgia universalis is the famous combinatoric system of composition, one of Kircher’s most celebrated inventions (Murata 2000; McKay 2012). The devices allowed even those untrained in music to write four-part counterpoint for a text in any language employing a series of tables and permutational rules, to produce the kind of compositions that Kofi Agawu identifies as instrumental in deploying “tonality as a colonizing force” (Agawu 2016). Indeed, Kircher writes,

Since the attraction of barbarians consists in the practice of music and the frequent praise of God, but they not always have printed books or even composers at hand, the Fathers believed that they could use this Musurgia very well in the future because they would be able to use it to produce songs not only in Latin but also in any given language, including those of the Indies, and in any barbaric language (MU B 3-4).

Montiel had this precise aim in mind when he carried the first copy of the Musurgia to the Indies. Muñoz must also have sensed its utility, as he devoted most of his Musicalia speculativa to carefully reproducing the various devices. Favián extolled one of such devices, the arca musarithmica, as “something as new and admirable that not enough human languages existed to praise it.”[6] Kircher’s interest in the use of music to “attract barbarians” is neither idiosyncratic musing nor bombastic sales pitch, but a concern for the Jesuits who were already deploying the affective power of music as a central weapon in their colonizing war against the Indigenous people of America.

Whether Jesuits did arrive to employ Kircher’s musicolonial war machines in the reducciones, we will never know. After all, the compositions produced with the combinatorial systems were designed to be ephemeral objects, not lasting “works.” They were conceived in order to exploit human musicking capacities to “domesticate”—as one Jesuit put it—the untold number of Indigenous peoples who inhabited the reducciones between 1549 and 1776.[7] From Montiel and Muñoz we know that Kircher’s contemporaries understood the mechanism and found it useful for these very purposes. To see these and other devices solely as musical (or music-theoretical) works, scientific objects, or even mere curiosities and not as affective weapons of colonization is, sadly, another symptom of the white frame of music studies.

Agawu, V. Kofi. 2016. “Tonality as a Colonizing Force in Africa.” In Audible Empire: Music, Global Politics, Critique, edited by Ronald Michael Radano and Tejumola Olaniyan, 334–355. Durham: Duke University Press.

Barnett, Gregory. 2002. “Tonal Organization in Seventeenth-century Music Theory.” In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, edited by Thomas Christensen, 407–455. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bauer, Ralph, and José Antonio Mazzotti. 2012. “Introduction: Creole Subjects in the Colonial Americas.” In Creole Subjects in the Colonial Americas, edited by Ralph Bauer and José Antonio Mazzotti, 14–78. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Camenietzski, Carlos Ziller. 2004. “Baroque Science between the Old and the New World: Father Kircher and His Colleague Valentin Stansel (1621–1705).” In Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything, edited by Paula Findlen, 311–328. New York: Routledge.

Cruz, Juana Inés de la. 2009. Obras completas I: Lírica personal. Edited by Antonio Alatorre. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Findlen, Paula. 2004. “A Jesuit’s Books in the New World: Athanasius Kircher and His American Readers.” In Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything, edited by Paula Findlen, 329–364. New York: Routledge.

Finley, Sarah. 2014. “Acoustic Epistemologies and Aurality in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” PhD diss., University of Kentucky.

Gumilla, Joseph. 1946 [1745]. El Orinoco ilustrado. Vol. 3. Madrid: M. Aguilar.

Kircher, Athanasius. 1650. Musurgia universalis, sive Ars magna consoni et dissoni. 2 vols. Rome: Haeredum Francisci Corbelletti/Typis Ludovici Grignani. Reprint, Facsimile edition: Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1970 ed. Ulf Scharlau.

———. 1667. Magneticum naturae regnum sive Disceptatio physiologica. Rome: Ignatii de Lazaris.

Lester, Joel. 1989. Between Modes and Keys: German theory 1592-1802. Stuyvesant: Pendragon Press.

Lyon, J. Vanessa. 2017. “‘My Original, A Woman’ Copies, Origins, and Sor Juana’s Iconic Portraits.” In Routledge Research Companion to the Works of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, edited by Emilie L. Bergmann and Stacey Schlau, 91–106.

Martínez-San Miguel, Yolanda. 2017. “The Creole Intellectual Project: Creating the Baroque Archive.” In Routledge Research Companion to the Works of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, edited by Emilie L. Bergmann and Stacey Schlau, 12–22. New York: Routledge.

McKay, John Zachary. 2012. “Universal Music-Making: Athanasius Kircher and Musical Thought in the Seventeenth Century.” PhD diss., Harvard University.

Murata, Margaret. 2000. “Music History in the Musurgia universalis of Athanasius Kircher.” In The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540–1773, 190–207. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Olivares Zorrilla, Rocío. 2015. “El modelo de la espiral armónica de sor Juana: entre el pitagorismo y la modernidad.” Literatura Mexicana 26 (1): 11–39.

Ortiz, Mario A. 2007. “La musa y el melopeo: Los diálogos transatlánticos entre Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y Pietro Cerone.” Hispanic Review 75 (3): 243–264.

Osorio Romero, Ignacio. 1993. La luz imaginaria: epistolario de Atanasio Kircher con los novohispanos. México, D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Paz, Octavio. 1982. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz o las trampas de la fé. Barcelona: Seix Barral.

Powell, Amanda. 2017. “Passionate Advocate: Sor Juana, Feminisms, and Sapphic Loves.” In Routledge Research Companion to the Works of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, edited by Emilie L. Bergmann and Stacey Schlau, 63–77.

Saldívar, Gabriel. 1934. Historia de la música en México. México: Publicaciones del Departamento de Bellas Artes.

Sarduy, Severo. 2013. “Barroco.” In Obras III. Ensayos, 129–224. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Stevenson, Robert. 1996. “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s Musical Rapports: a Tercentenary Remembrance.” Inter-American Music Review 15 (1): 1–21. https://iamr.uchile.cl/index.php/IAMR/article/view/52869/55465.

Trabulse, Elías. 1998. “El tránsito del hermetismo a la ciencia moderna: Alejandro Fabián, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora.” Calíope 4 (1/2): 56–69.

Villegas Vélez, Daniel. 2022. “Apparatus of Capture: Music and the Mimetic Construction of Social Reality in the Early Modern/Colonial Period.” CounterText 8 (1).

[1] Alejandro Favián, Letter to Athanasius Kircher, Puebla, February 2, 1661. Kircher’s correspondence with Favián was reconstructed by Ignacio Osorio Romero (1993).

[2] Translation in Trabulse (1998, 58)

[3] On the epistemological basis of Kircher’s “credulity,” see Camenietzski (2004, 322)

[4] I follow Amanda Powell’s choice of the term “Sapphic” to indicate both the presence and the irreducibility to modern notions of lesbian love in Sor Juana’s textual personae, inscribed in between sexuality and literary construction (Powell 2017).

[5] While intriguing, the thesis that the spiral was a critique of Zapotec composer Juan Mathias rests on tenuous evidence and is more likely the product of Gabriel Saldívar’s elevation of sor Juana as the Mexican national heroine above Indigenous musicians (Saldívar 1934, 130).

[6] Alejandro Favián, Letter to Athanasius Kircher, Puebla, May 9, 1663. (Osorio Romero 1993, 30)

[7] “It has been experimented in the Missions we have founded how much they are attracted and domesticated by music, how much they appreciate it and how proud they are those whose children have been destined by the missionary for music school.” (Gumilla 1946[1745], 515). For the role of mimetic musical performance in the reducciones and the Jesuit notion of the human, see (Villegas Vélez 2022)