Part I. Musicosmopolitics

Few music treatises circulated in the early modern/colonial period as broadly and efficiently as Athanasius Kircher’s Musurgia universalis (1650).[1] Of the 1500 printed copies of the Musurgia, 300 were given to Jesuit missionaries who distributed it around the globe: “et in Africam, Asiam et Americam distracta fuerunt.”[2] The copy in the Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá (which has housed the library of the Jesuit College since its 1767 expropriation), is registered as “Ex-libris: ms. Provincia Novi Regni donum authoris.”[3] The book reached readers across the globe, in particular those in the Spanish colonies, where Kircher would become a point of reference in late-seventeenth century scientific circles (Trabulse 1998). In this post, I draw from my forthcoming manuscript, Mimetologies: Mimesis and Music 1600–1850 (Oxford University Press) to examine how three of Kircher’s readers—situated at different points of racial and gender spectrums—responded to the Jesuit’s works: Ignacio Muñoz, a Spanish Dominican friar; Alejandro Favián, a criollo priest from Puebla; and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the most notable intellectual of her time.

The global circulation of the Musurgia universalis was, in a sense, already inscribed in the universalist ambitions of its title, which translates roughly to “the musical performance of the universe.” In the Musurgia, music is not merely a subdiscipline of mathematics or a humanist craft, but a way of understanding the universe. In Kircher’s idiosyncratic brand of Hermetic Neoplatonism, the universe or kosmos is organized musically and in “perfect imitation” of the Creator, so that understanding the empirical manifestations of music across the globe constitutes true knowledge of God. A sentence attributed to Hermes Trismegistus inscribed in the frontispiece of the second volume puts it succinctly: “Musica nihil aliud est, quam omnium ordinem scire.” [Music is nothing else than knowing the order of everything].

If few music treatises have such universalist ambitions, it is even more rare to find the political implications of these ambitions made explicit in the work itself. In the dedicatory to Archduke Leopold William of Austria, Governor of the Spanish Netherlands and brother to Emperor Ferdinand III, Kircher evokes the bitter memories of the Thirty Year’s War as he introduces the Musurgia as that art by which the Prince “restores customs to the harmonious tranquility of peace in the most dissonant times of the Christian Republic” (MU B 366).[4] More than a conventional turn of phrase, Kircher expands on the claim in book X through a detailed analysis of the forms of government according to the theory of musical means, going on to declare Christian monarchy (a harmonic proportion in which the sovereign distributes everything among the best people according to their virtue and merits) as the best form of government. According to Kircher, one studies music not simply to “know everything,” but to know how to rule everything according to such knowledge.

I adventure the (admittedly baroque) term “Musicosmopolitics” to describe this blend of (musical and cosmological) knowledge and politics. I suggest that most music treatises contain such a blend of knowledge and politics, even when the political consequences of their epistemic claims are—purposefully or not—hidden from view. This, I believe, is what Philip Ewell (2020) means when he speaks about music theory’s “white frame.” While the Musurgia is not unique in this respect, it is a fruitful text to examine from this perspective because it is explicit about its musicosmopolitics. Kircher took the term “universal” seriously: the Musurgia integrates, in a single narrative of Catholic revelation and salvation, all forms of music-making from antiquity to his time. For this, he draws from the library of the Collegio Romano as well as two epistolary networks of which Kircher himself was a central node: the European Respublica literaria and the missionaries of the Society of Jesus stationed in China, Japan, India, South East Asia, Africa, and America. The Musurgia is conceived as an ars politica—a means to command and control the mores of the people through harmony. More precisely, the Ars consoni, et dissoni explains the mutual belonging of consonance and dissonance as an all-pervasive ontological condition, a universal principle: “Consonum sine dissono, dissonum sine consono subsistere nequaquam posse Deus, Natura, Politice, docet” (MU A [IX]). [God, Nature and Politics teach that neither consonance without dissonance nor dissonance without consonance can subsist.] Thus seen, the Musurgia was “a global design,” to use Walter Mignolo’s formulation, an account of how the world is and how it should be organized, written in such a way that the provinciality of its Eurocentric, Catholic enunciations are obscured under a presumed universality that simultaneously delegitimizes alternate conceptions—hence a uni-versal (Mignolo 2021, 184). Attending to its diverse readers allows us to appreciate the scope and limitations of the Musurgia’s global design.

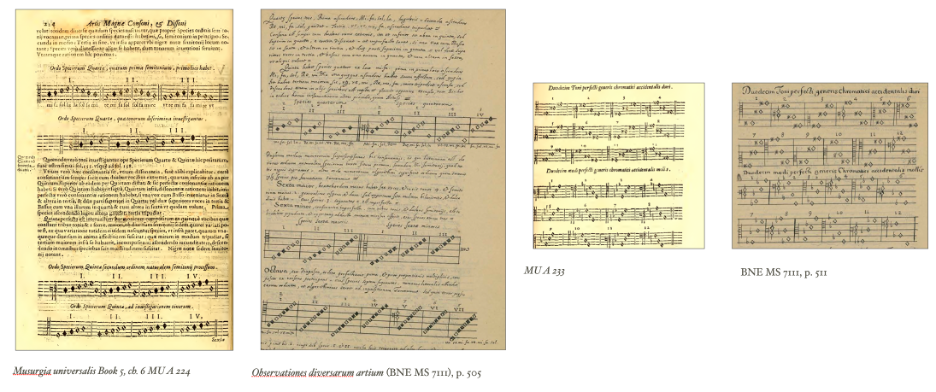

The Musurgia arrived in the Philippines just four years after its publication, transported by one of Kircher’s pupils, Giovanni Montiel. For the young missionary, the Musurgia was “of great usefulness to the Fathers of the missions, where music is taught publicly.”[5] Ten years later, Ignacio Muñoz, a Dominican friar then stationed in Manila, began copying lengthy passages from the Musurgia into a manuscript volume titled Observationes diversarum artium (Muñoz 1662-77; González Acosta 2001, 220; Bordas, Robledo, and Knighton 1998, 408).[6] Muñoz—who was employed as a royal hydrographer responsible for updating the navigation charts employed by Spanish merchants, colonizers, and slave traders—devoted more than a hundred manuscript pages to a section titled Musicalia speculativa.

Under close examination, the section on music reveals itself as a copy of the Musurgia, organized by books and summarized into postulates, diagrams, and tables that synthesize its contents. Lacking in Muñoz’s version, however, is the entire musicosmopolitical framework of Kircher’s work: with its redactions and its focus on the technical aspects of music-making, Observationes comes to resemble more traditional music handbooks of its time. This is not to say that Muñoz’s copy is less universalist than Kircher’s. Rather, his careful efforts at copying the Jesuit’s work reveals how close the Musurgia was to Muñoz’s own project of charting the globe to facilitate Spanish domination. The globe Kircher described more musico was certainly not the same globe Muñoz measured more geometrico, yet the two found themselves co-inscribed in the pages of the Observationes where they shared the common task of deploying the colonial global design of Catholic Spain in the so-called “New World.”

Bordas, Cristina, Luis Robledo, and Tess Knighton. 1998. “José Zaragozá’s Box: Science and Music in Charles II’s Spain.” Early Music 26 (3): 391–413. https://doi.org/10.2307/3128699.

Ewell, Philip A. 2020. “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame.” Music Theory Online 26 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.2.4.

Feagin, Joe R. 2010. The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Racial Framing and Counter-Framing. New York: Routledge.

Fletcher, John Edward. 2011. A Study of the Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher, ‘Germanus Incredibilis’: With a Selection of His Unpublished Correspondence and an Annotated Translation of His Autobiography. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

González Acosta, Alejandro. 2001. “Buenas nuevas para los estudiosos: hallazgos bibliográficos mexicanos en Europa y Estados Unidos.” Boletín Millares Carlo 20: 219–229.

Irving, David R. M. 2009. “The Dissemination and use of European Music Books in Early Modern Asia.” Early Music History 28: 39–59.

Kircher, Athanasius. 1650. Musurgia universalis, sive Ars magna consoni et dissoni. 2 vols. Rome: Haeredum Francisci Corbelletti/Typis Ludovici Grignani. Reprint, Facsimile edition: Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1970 ed. Ulf Scharlau.

Mignolo, Walter. 2021. The Politics of Decolonial Investigations. Durham: Duke University Press.

Muñoz, Ignacio. 1662-77. “Observationes diversarum artium.” Biblioteca Nacional de España. MS 7111.

Trabulse, Elías. 1998. “El tránsito del hermetismo a la ciencia moderna: Alejandro Fabián, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora.” Calíope 4 (1/2): 56–69.

[1] Kircher, Athanasius. Musurgia universalis, sive Ars magna consoni et dissoni. 2 vols. Rome: Haeredum Francisci Corbelletti/Typis Ludovici Grignani, 1650. Facsimile edition: Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1970 ed. Ulf Scharlau.

[2] Kircher to Joannes Jansson, n.d., Kircher MS 561, fol. 79r., Archivio della Pontificia Università Gregoriana, Rome. Quoted in (Fletcher 2011, 417)

[3] Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, RG 4019.

[4] I follow the convention of referring to the volumes of the Musurgia as MU A and B respectively, followed by page numbers.

[5] Giovanni Montèl [Montiel], Letter to Kircher, 15 July 1654, Archivio della Pontificia Università Gregoriana, Rome APUG 567, fol. 155r. Accessed through the Stanford University’s Kircher Correspondence Project. Translation in (Irving 2009, 46; Fletcher 2011, 219)

[6] The section on music was first identified as a digest of the Musurgia by David Irving, who attributed it to an anonymous Jesuit (Irving 2009). Muñoz, however, was a Dominican and had no teaching appointments at the Jesuit College in Manila. He was briefly appointed to the chair of Mathematics in Mexico before returning to Spain. It is unclear if he ever took the post.