[…] Continuation of: Part I

Mehdi-Qoli Hedāyat (1863–1955) (also known as Mokhber-al Saltaneh) (Figure 1), is the twentieth-century Persian musicologist who decoded this Abjadic tone-letter system and combined it with the Western rhythmic notation to create a modern fusion notation!

مهدیقلی هدایت (۱۸۶۳ – ۱۹۵۵ م.) (ملقّب به مخبرالسّلطنه) (تصویر ۱)، موسیقیشناس ایرانی قرن-بیستمی است که این سیستم حرف-نغمهای ابجدی را رمزگشایی کرد و آن را با نتنویسی ریتمیک غربی ترکیب نمود، تا یک روش نغمهنگاری تلفیقی مدرن ایجاد کند!

تصویر 1: مهدیقلی هدایت (ملقّب به مخبرالسّلطنه) (۱۸۶۳ – ۱۹۵۵ م.)

A prominent Iranian politician during the late Qajar and the early Pahlavi era, Hedāyat revived the forgotten musical treatises of the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries after his retirement from government positions, encouraged by his long-standing interest in music. His excellent fluency in Arabic and German, and his acquaintance with the European and Persian-Arabic musical systems enabled him to present the first modern Persian music theory treatise. His Majma-al-Adwār (“The collection of [modal and rhythmic] Cycles”), published in 1938, is a comprehensive review of the early and contemporary Persian musical system combined with some of Hermann Helmholtz’s (1821–1894) ideas on the acoustical and physiological aspects of musical tones. In an appendix to this book, entitled Dastur-e Abjadi dar ketābat-e musiqi (“The Abjadic instruction in music notation”), Hedāyat describes the details of a fusion notation method, which does not require any staff, accidentals, ledger lines, or clefs (Hedāyat, 1938, Dastur-e Abjadi appendix 4; 2009, 44). This method, which is designed for the traditional Persian string instrument setār (Figure 2) —the reference instrument of Persian dastgāh music— combines the seventeen[1] Abjadic tone-letters and the Western system of metrical time values.

هدایت، سیاستمدار برجسته ایرانی در اواخر قاجار و اوایل پهلوی بود که علاقه دیرینهاش به موسیقی، او را به احیای رسالات فراموششده موسیقایی قرن سیزدهم تا پانزدهم میلادی، پس از بازنشستگی از سمتهای دولتیاش، وا داشت. او به دلیل تسلط عالی به زبانهای عربی و آلمانی، و آشنایی با سیستم موسیقی اروپایی و ایرانی، توانست نخستین رساله موسیقی ایرانی معاصر را ارائه دهد. “مجمعالادوار” او که در سال ۱۹۳۸ میلادی منتشر شد، مروری جامع بر سیستم موسیقایی قدیمی و معاصر ایرانی و برخی از ایدههای هِرمان هِلمهُولتز[1] (۱۸۲۱ – ۱۸۹۴ م.) درباره جنبههای آکوستیکی و فیزیولوژیکی نغمات موسیقایی است. هدایت در ضمیمه این کتاب با عنوان “دستور ابجدی در کتابت موسیقی” جزئیات یک روش نتنویسی تلفیقی، که به استفاده از خطوط حامل، علامتهای عرضی، خطوط حامل کمکی، و کلیدها، نیازی ندارد را شرح میدهد. (هدایت، ۱۳۱۷، ضمیمه دستور ابجدی ص ۴؛ ۱۳۸۸، ۴۴). این روش که برای ساز سهتار (تصویر ۲) —ساز مرجع موسیقی دستگاهی ایرانی— طراحی شده است، ترکیبی از حروف هفدهگانه[2] ابجدی و سیستم ارزشهای زمانی غربی است.

تصویر 2: سهتار (ساز سنتی زهی ایرانی)

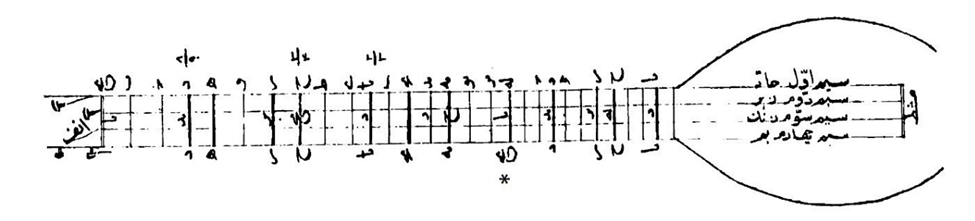

Hedāyat demonstrates the place of the entire Abjadic tone-letters on a setār fretboard (Figure 3), at the beginning of the Dastur-e Abjadi appendix.

هدایت محل حروف-نغمات ابجدی را بر روی دستانهای سهتار (تصویر ۳)، در ابتدای ضمیمه دستور ابجدی نشان میدهد.

تصویر 3: دستانبندی سهتار (هدایت، ۱۳۱۷، ضمیمه دستور ابجدی ۷-۸؛ ۱۳۸۸، ۴۶-۴۷)

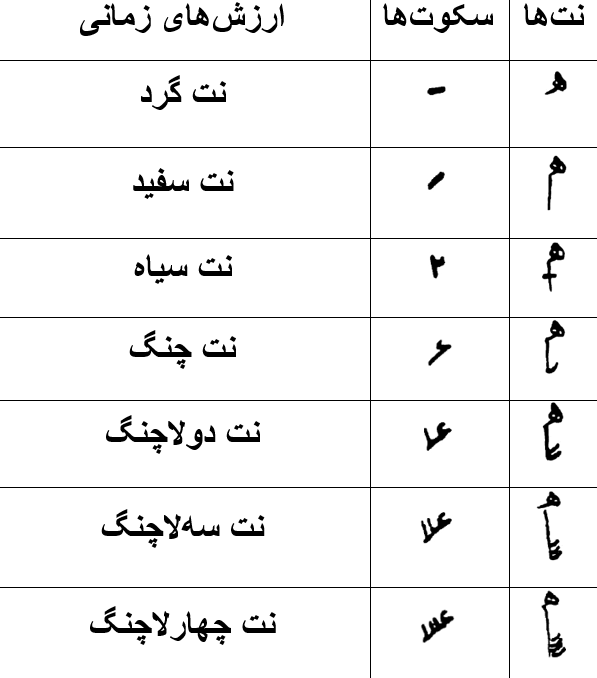

Hedāyat’s innovation was to combine the Abjadic tone-letters with Western durational notation in order to express a more accurate presentation of rhythm and meter. The traditional way of displaying time values in thirteenth-century treatises[1] was in a way that the duration of each tone-letter, as a positive integer, 1, 2, 3, etc. (1 being the smallest time value) was written from right to left in a parallel horizontal line below the melody line. [2] Hedāyat applies the Western metric structure, with a slight alteration in details, to his system. For instance, for a whole note duration, he only uses the Abjadic letter itself without a stem.

Then he adds the stem to show a half note time value.

And since there is no elliptical neume as the notehead that makes a differentiation whether it is being filled or unfilled, he adds a little horizontal line to the stem to distinguish the quarter note value.

The rest of his time duration signs follow the same Western system, although with the Abjadic letter noteheads.

The rest values also largely follow the same rules as in the Western system. Below, you can find the table of note and rest values in Hedāyat’s notation. He also applies some other Western metric and repetition signs in the same way.

بدعت هدایت در تلفیق حروف-نغمات ابجدی با علائم زمانی نتنویسی غربی، بهمنظور ارائه دقیقتر ریتم و متر بود. روش سنتی نمایش ارزشهای زمانی در رسالات قرن-سیزدهمی میلادی[1] بهاین ترتیب بود که دیرند هر حرف-نغمه، بهصورت یک عدد صحیح مثبت، ۱، ۲، ۳، و غیره (که عدد ۱ کوچکترین ارزش زمانی است) در خطی افقی موازی در زیر خط ملُدی نوشته میشد.[2] هدایت همان ساختار متریک غربی را، با اندک تفاوتهایی در جزئیات، در سیستم خود اعمال میکند. بهعنوان مثال، برای ارزش زمانی نت گرد، او فقط از خود حرف ابجدی بدون دُم استفاده میکند.

سپس برای نشان دادن نت سفید، دُم را به حرف ابجدی اضافه می کند.

و از آنجا که سرنُتِ بیضیشکلی وجود ندارد که پر بودن یا پر نبودن آن تمایزی ایجاد کند، او یک خط افقی کوچک به دُم نت اضافه میکند تا ارزش زمانی نت سیاه را مشخص کند.

سایر علائم ارزشهای زمانی او از همان سیستم غربی، گرچه با سرنتهای ابجدی، پیروی میکند.

ارزشهای زمانی سکوتها نیز تا حد زیادی از قوانین مشابه در سیستم غربی پیروی میکند. در زیر میتوانید جدول مقادیر نتها و سکوتها را در روش نتنویسی هدایت بیابید. او همچنین برخی دیگر از نشانههای متریک و تکرارهای سیستم نتنویسی غربی را به همان صورت اعمال میکند.

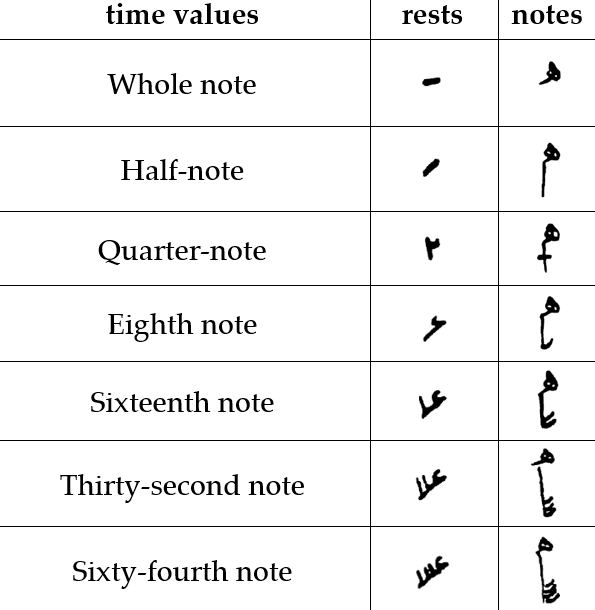

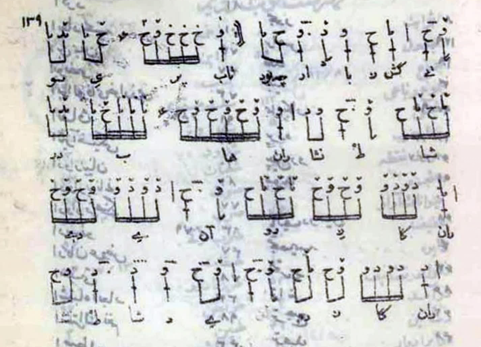

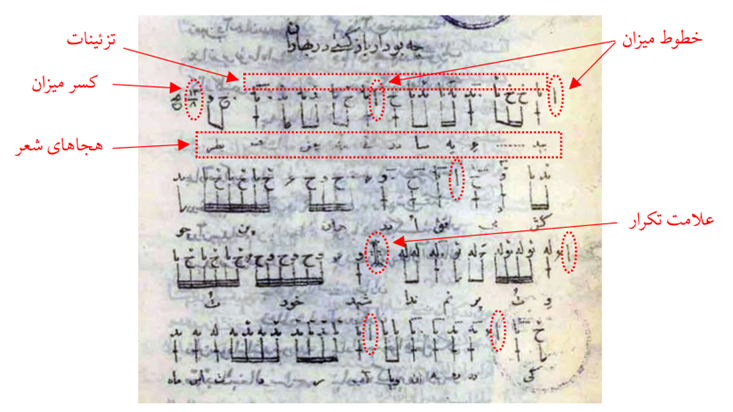

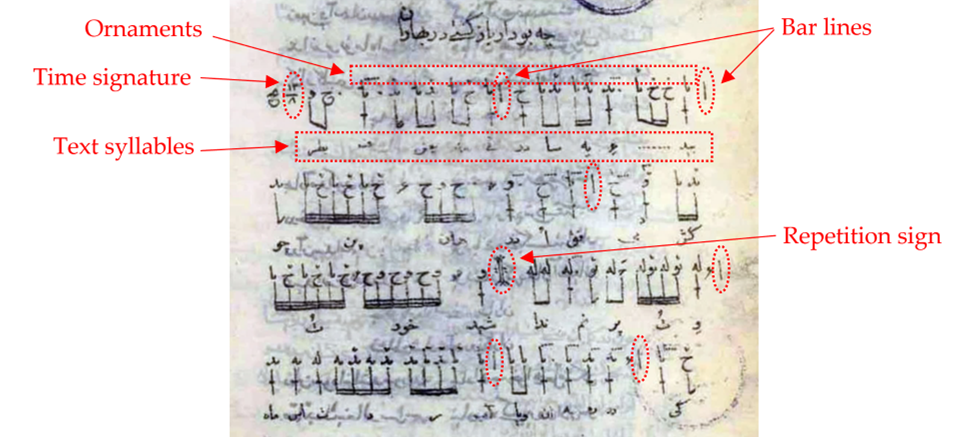

The only example of a song-text[1] notated with Hedāyat’s method in Majma-al-Adwār (Figure 4), can be found at the end of the second section of this book, under the title “Che bud ar bāzgashti dar bahārān“(What if you came back in spring) (ibid, 1938, second section 138-139). The song is a simple melody line in the dastgāh-e Šur (one of the modes in Persian Dastgāh music) with a D tonal center and a twelve-eight meter, written from left to right. Along the notated horizontal melody lines, other than the Abjadic letters and their time values, you can also find the vertical bar lines, some repetition signs, and the ornaments (designed for setār), as well as the syllables of the text’s words which are written precisely in another parallel horizontal line under the tone-letters, which, of course, is contrary to the tradition of right-to-left notation in thirteenth-century treatises (Figure 5).

تنها نمونه تصنیفی که بهروش هدایت در مجمعالادوار نتنویسی شده است (تصویر ۴) را میتوان در انتهای بخش دوم این کتاب، با عنوان “چه بود ار بازگشتی در بهاران” یافت (همان، ۱۳۱۷، بخش دوم ۱۳۸-۱۳۹). این تصنیف، یک خط ملُدی ساده در دستگاه شور، با نت شاهد ر و قالب زمانی ۸/۱۲، است که از چپ به راست نتنویسی شده است. در خلال خطوط افقی ملُدی، بهغیر از حروف ابجدی و مقادیر زمانی آنها، میتوانید خطوط عمودی میزان و برخی علامتهای تکرار، و علامتهای تزئین (مخصوص سهتار)، و همچنین هجاهای کلمات شعر که در خط موازی دیگری در زیر حروف-نغمات بهدقت نوشته شده است را نیز ملاحظه کنید، که البته با سنت نغمهنگاری راست-به-چپ در رسالات قرن-سیزدهمی میلادی در تعارض است (تصویر ۵).

(Hedāyat, 1938, second section 138-139)

تصویر 4: تصنیف نغمهنگاری شده با روش هدایت، در کتاب مجمعالادوار

(هدایت، ۱۳۱۷، بخش دوم ۱۳۸-۱۳۹)

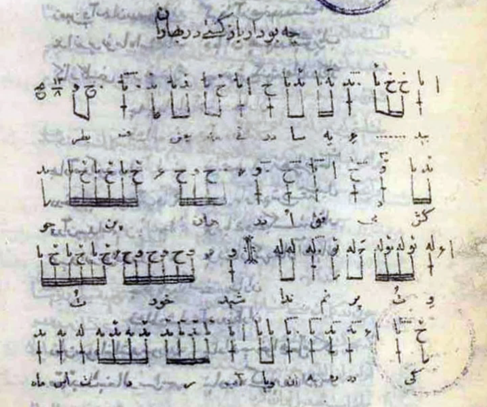

Below (Figure 6), you see my transcription of this two-page song-text. I have used Ali-Naqi Vaziri’s koron(quarter-flat) accidental sign to demonstrate the approximation of neutral intervals in twenty-four equal quartertone temperament. I have also copied the ornamentation signs, exactly as they are written in Hedāyat’s notation.

در زیر (تصویر ۶)، ترانویسی من از این تصنیفِ دو صفحهای را مشاهده میکنید. من برای نشان دادن تقریبِ فواصل خنثی در گام بیستوچهار ربعپردهای متساوی، از علامت عرضی کُرُنِ علینقی وزیری استفاده کردهام. علامتهای تزیینی را نیز دقیقاً همانگونه که در روش نتنویسی هدایت نوشته شده است منتقل کردهام.

تصویر 6: ترانویسی من از تصنیف نغمهنگاری شده توسط مهدیقلی هدایت

Hedāyat’s hybrid notation makes a bridge between the present and the past, which allows us to study the history of Persian music theory —which in recent decades has been theorized using the twenty-four equal quartertone temperament— through the forgotten seventeen-tone system which was designed specifically for this music and used for at least seven centuries. Hedayat’s hybrid notation dispenses with staff, accidentals, ledger lines, and clefs; making it particularly suitable for Persian musicians whose main priority is to deliver a melody line full of subtle ornamentations in the small range of a traditional instrument. However, whether or not Abjadic-Metric notation can be a viable alternative to today’s widely used Western notation for Persian music would be difficult to answer.

روش نغمهنگاری تلفیقی هدایت پلی بین زمان حال و گذشته برقرار میکند، که امکان مطالعه تاریخ تئوری موسیقی ایرانی —که در دهههای اخیر با استفاده از گام بیستوچهار ربعپردهای متساوی تئوریزه شده است— را از طریق سیستم فراموششدهی هفده-نغمهای، که مخصوص این موسیقی طراحی شده و دستکم برای هفت قرن استفاده میشده است، برای ما امکانپذیر میکند. عدم نیاز نغمهنگاری تلفیقی هدایت از خطوط حامل، علامتهای عرضی، حاملهای کمکی، و کلیدها، آنرا بهویژه برای موسیقیدانان ایرانی، که اولویت اصلی آنها ارائه یک خط ملُدی پر از تزئینات ظریف در محدوده یک ساز سنتی میباشد، مناسب میکند. بااینحال، پاسخ به این پرسش که آیا نغمهنگاری ابجدی-نقطهای میتواند جایگزین مناسبی برای نتنویسی غربیِ فراگیرِ امروزی برای موسیقی ایرانی باشد یا خیر، دشوار است.

Reference List

Daemi Milani, Farzad, and Hooman Asadi. 2021. “An analysis and transcription of a song-text notated in a fusion notation method (Abjadic-metric) by Mehdi-Gholi Hedāyat (Mokhber-al Saltaneh), considering the suggested intervals of Montazam-al Hokamā'”. Honar-Ha-Ye-Ziba: Honar-Ha-Ye-Namayeshi Va Mosighi 26, no. 1 (Spring): 5-12.

Farhat, Hormoz. 1965. “The Dastgah Concept in Persian Music”. PhD diss., University of California.

Farmer, Henry George. 1929. A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century. Luzac oriental.

Hedāyat, Mehdi-Qoli. 2009. “Dastur-e Abjadi”. Māhur Quarterly. Vol 11, No. 44: 43-63.

———. 1938. Majma-al-Adwār (A Complete Overview of Music from Abd al-Mu’min to Helmholtz). Tehran.

Helmholtz, Hermann L F, and Alexander J Ellis. 1895. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music, the third edition, London: Longmans, Green, and Co. and New York.

Land, Jan Pieter Nicolaas. 1884. Recherches sur l’histoire de la Gamme Arabe. EJ Brill.

Lemaire, Alfred. 1900. Avâz et Tèsnǐf Persans. Paris: H. Jacques Parès.

Lucas, Ann E. 2010. Music of a Thousand Years: A New History of Persian Musical Traditions. Los Angeles: University of California.

Maalouf, Shireen. 2003. “Mīkhāʾīl Mishāqā: Virtual founder of the twenty-four equal quartertone scale.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 123, No. 4, (Oct. – Dec.): 835-840.

Mohammadi, Mohsen. 2017. “Modal Modernities: Formations of Persian Classical Music and the Recording of a National Tradition.” PhD diss., Utrecht University.

Nettl, Bruno. 1992. The Radif of Persian Music: Studies of Structure and Cultural Context, rev. ed. Champaign, Ill.: Elephant and Cat.

Partch, Harry. 1949. Genesis of a Music: An account of a creative work, its roots and its fulfillments. Second edition, Da Capo Press.

Wright, Owen. 1994. “Abd al-Qādir al-Marāghī and Alī b. Muḥammad Binā’ī: two fifteenth-century examples of notation. Part 1: Text.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 57, no. 3: 475-515.

———. 1978. The Modal System of Arab and Persian Music A.D. 1250-1300. London: Oxford university press.

فهرست منابع

دائمی میلانی، فرزاد، و هومان اسعدی. ۱۴۰۰. “بررسی و ترانویسی تصنیفی نغمهنگاریشده به شیوۀ تلفیقی (ابجدی-نقطهای) از مهدیقلی هدایت (مخبرالسّلطنه)، با نگاهی به فواصل پیشنهادی منتظمالحکماء”. نشریه هنرهای زیبا-هنرهای نمایشی و موسیقی، ۲۶(۱) (بهار): ۵-۱۳.

دائمی میلانی، فرزاد. ۱۳۹۸. بررسی و تحلیل سیرِ تحوّلِ نغمهنگاری(نُتاسیون) در موسیقیِ ایران و جهانِ اسلام. پایاننامۀ کارشناسی ارشد رشتۀ پژوهش هنر، مرکز پیام نور تهران شرق، دانشگاه پیام نور استان تهران.

فارمر، هنری جورج. ۱۳۹۷. تاریخ موسیقی خاور زمین، ایران بزرگ و سرزمینهای مجاور تا سقوط خلافت عباسیان (ترجمه: بهزاد باشی). تهران: انتشارات معین.

محمدی، محسن. ۱۳۹۳. نظام دستگاه در موسیقی ایران به روایت آلفرد لومر و اوژن اوبن. فصلنامه موسیقی ماهور، 64: 133-138.

هدایت، مهدیقلی. ۱۳۸۸. دستور ابجدی در کتابت موسیقی. فصلنامۀ ماهور. شماره ۴۴: ۴۳-۶۳.

همان. ۱۳۱۷. مجمعالادوار، دوره کامل موسیقی از عبدالمؤمن تا هلمهلص، چاپ سنگی. طهران.

همان. ۱۳۰۱. ردیف موسیقی ایرانی. کتابخانه دانشگاه هنر تهران، نسخه خطّی.

Farhat, Hormoz. 1965. “The Dastgah Concept in Persian Music”. PhD diss., University of California.

Farmer, Henry George. 1929. A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century. Luzac oriental.

Helmholtz, Hermann L F, and Alexander J Ellis. 1895. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music, the third edition, London: Longmans, Green, and Co. and New York.

Land, Jan Pieter Nicolaas. 1884. Recherches sur l’histoire de la Gamme Arabe. EJ Brill.

Lemaire, Alfred. 1900. Avâz et Tèsnǐf Persans. Paris: H. Jacques Parès.

Lucas, Ann E. 2010. Music of a Thousand Years: A New History of Persian Musical Traditions. Los Angeles: University of California.

Maalouf, Shireen. 2003. “Mīkhāʾīl Mishāqā: Virtual founder of the twenty-four equal quartertone scale.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 123, No. 4, (Oct. – Dec.): 835-840.

Nettl, Bruno. 1992. The Radif of Persian Music: Studies of Structure and Cultural Context, rev. ed. Champaign, Ill.: Elephant and Cat.

Partch, Harry. 1949. Genesis of a Music: An account of a creative work, its roots and its fulfillments. Second edition, Da Capo Press.

Wright, Owen. 1994. “Abd al-Qādir al-Marāghī and Alī b. Muḥammad Binā’ī: two fifteenth-century examples of notation. Part 1: Text.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 57, no. 3: 475-515.

———. 1978. The Modal System of Arab and Persian Music A.D. 1250-1300. London: Oxford university press.