An appendix with side-by-side translations of the original texts can be found at the end of this post for the reader’s reference.

“The Chinese Cadence”?

A while back, I was part of a Chinese Music Ensemble at an American institution. I remember the director urging us to bring out the expressiveness of a certain cadence, describing it as “very traditionally Chinese.” As a pipa player, I sympathized with their view about this progression—an A major triad moving to a D major triad, often accompanying a G major pentatonic melody ending on D. This cadence indeed appears in many canonic pieces for Chinese orchestra. To highlight its significance, I’ve compiled examples in the audiovisual collage below (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Collage showcasing “the Chinese cadence” across multiple pieces.

In many contexts, these cadences may pass as ordinary dominant-tonic function progressions for classically trained musicians. But how do they register a distinctively Chinese meaning for the director and me?

Many aspects of Western music theory functions, ranging from pitch conception to tertian and functional harmonies, have firmly taken root in modern Chinese musicians’ consciousness. Over time, these theories have been uniquely adapted in China, allowing Western musical devices like the simple A-D progression to create new, Chinese-specific idioms and meanings. In this blog, I explore some localization processes of Euro-American harmonic theories into Chinese musical constructs in the twentieth century. First, I will discuss the range of perspectives toward incorporating Western musical concepts into Chinese musical thought. Then, I will describe a localized harmony system based on functional harmony and apply it to the A-D progression in the modern Chinese context.

Early Efforts in Sinifying Tertian Harmony

Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century China was an unstable period, marked by multiple defeats at the hands of foreign imperialist powers. In response, intellectuals and elites called for modernizing society to “save the nation.” To elevate what they saw as “backward” Chinese music, they adopted a social evolutionist attitude, embracing Western musical knowledge. Concepts like tertian harmony and tonality were introduced to the literate public through magazines and self-education manuals, and in the process of translating and reconciling Eastern and Western musical ideas, Chinese musicians applied different philosophies.1 In this context, the approaches of Liu Tianhua (劉天華,1895–1932) and Cheng Maoyun (程懋筠,1900–1957) exemplify the differing degrees of integration between the two cultures.

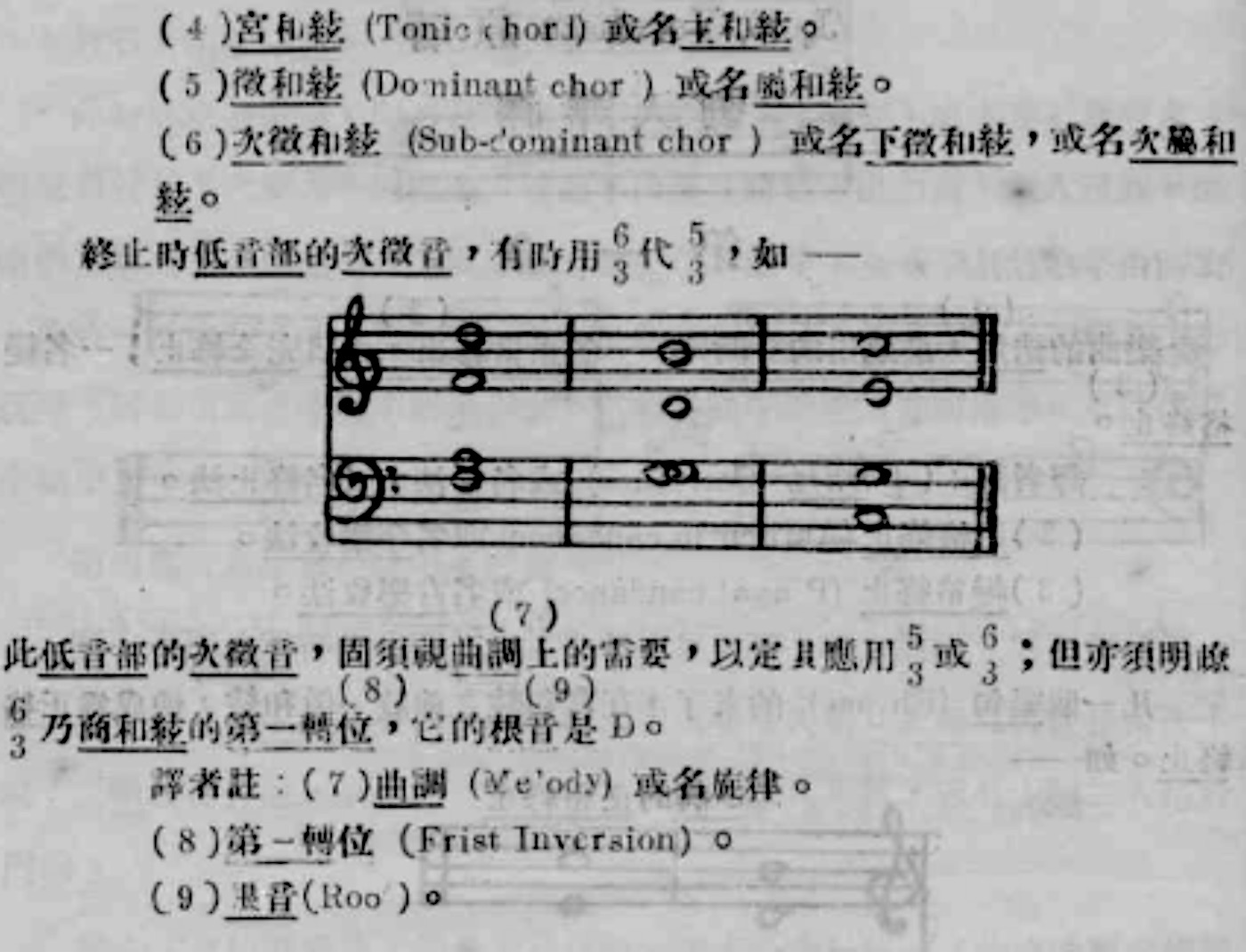

Today, Liu Tianhua is fondly remembered as a master composer for erhu and pipa, but his role in introducing Western music theory to the Chinese population is less frequently acknowledged. One of his notable contributions was his translation of First Steps in the Harmonization of Melodies by John Edward Vernham (1854–1921), one of the earliest Chinese translations of harmonic treatises, which was published in periodicals for music enthusiasts.2 In Fig.2, which discusses authentic and plagal cadences from the first page of Vernham’s text, functional harmony terms such as inversion, bass, and root were transliterated in Liu’s work. However, Liu adopted Chinese pentatonic-based scale naming system, instead of Arabic numerals to represent diatonic scale degrees, while still emphasizing the importance of fifth relations.3 For scale degrees 4 and 7, Liu translated the subdominant literally as “zi-zhi,” meaning “sub-zhi,” rather than using terms like bianzhi (lowered zhi) or qingjue (raised jue), which became the norm in later years. The leading tone is named both biangong (lowered gong) and the functional daoyin (guiding tone). Liu’s approach, therefore, highlights fifth relations and harmonic functions without abandoning the existing Chinese musical lexicon and concepts of scale.

Fig. 2. An excerpt from Liu Tianhua’s translation of Vernham’s First Steps in the

Harmonization of Melodies (ca. 1900), as published in Music Magazine Vol. 1, issue 2 (1928), 2.

In contrast, Cheng demonstrated an iconoclastic attitude towards Chinese music. His essay, “Suggestions for Improving Our Nation’s Music”(改良吾國音樂芻議, 1930/1933) began by outlining the “universal” elements of music— Western concepts of scales, rhythm, melody, and harmony—along with a solfège-based explanation of tonality (see Fig. 3).4 For him and some of his contemporaries, Chinese musical practice, driven primarily by melody, was monophonic, akin to medieval Gregorian chants. From their social evolutionist perspective, modernizing Chinese music required adopting the Western tonal and contrapuntal system to achieve the same degree of sophistication as European concert music.5

Fig. 3. Two excerpts from Cheng Maoyun’s “Suggestions for Improving Our Nation’s Music” (1930),

as printed in Music Education, Vol. I, Issue 1 (1933), found on pages 20, 26.

Constructing a Chinese Harmonic Theory in the Communist Era

These two modes of thought—modernizing existing Chinese musical processes versus treating Western musical constructs (considered universal) as the foundation for new Chinese music—were both influential in the development of modern Chinese music. This can be illustrated by methods of creating Socialist music in the era of the People’s Republic of China after 1949.

During the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), there was a strong demand for new mass songs and choral works for nationalist endeavors. While professionally trained musicians adapted regional folk songs with new lyrics and musical structures, knowledge of harmony, counterpoint, and form was still largely imported during this period. To meet the demand for training amateur musicians, theory textbooks by Percy Goetschius, Ebenezer Prout, A. Madeley Richardson, Anton Arensky, and Paul Hindemith, among others, were translated and published. Simultaneously, more materials on music fundamentals were written by Chinese musicians, and professionals began developing “Chinese” harmonic theories, resulting in works such as Wang Zhenya’s Pentatonic Scale and its Harmony (五聲音階及其和聲, 1950).

Building on these developments, Li Yinghai, with nearly 50 years of experience teaching harmony at Chinese conservatories, wrote Han Music and its Harmony (漢族音樂及其和聲, 1960/2001), providing a more mature perspective on Chinese harmony theory and pedagogy. His theory is built on two premises: (1) pentatonicism is fundamental to Han Chinese melodic construction, and (2) the “scientific nature” of the overtone series and perfect fifths supports the pentatonic collection as the foundation of Chinese music.6 Although pentatonic modal theory is considered sufficient for analyzing Han Chinese melodic construction, the lack of tritone and dissonant intervals in the scale limits harmonic variance. Instead, Li advocates using tertian harmony as a foundation, while carefully considering the Han musical style.7 To further support his theory on the Chinese origins of triadic harmonies, Li adopts three forms of heptatonic scales used in regional Han musics, with different kinds of seconds inserted between the two minor thirds—namely the Yayue, Qinyue, and Yanyue scales.8 He also provided justifications for not fully adopting Western four-part harmony idioms, suggesting more “appropriate” treatments for the pentatonic modes. For example, he views the use of parallel fourths and fifths as a useful way to depict modality, and recommends that the third of a triad should be omitted or substituted with a second or a fourth for modal colors.

Li’s theory illustrates how Western musical concepts were internalized and adapted within the consciousness of Chinese musicians. This growing fluency in tertian harmonies, combined with systematic studies of Chinese folk music, enabled them to reimagine these initially imported harmonic constructs into their own idioms, creating new paradigms unique to the landscape of Chinese music.

Conclusion

To conclude, I propose four possible explanations for the “Chinese” A-D progression discussed at the beginning of this essay, drawing on Li’s theory.

- The collection [D, E, F-sharp, G, A, B, C-sharp] represents the D yayue scale in D zhi mode, which is based on the pentatonic scale [D, E, G, A, B]. The A-D triadic progression functions as a dominant-tonic cadential progression (Excerpts 1, 4, 5).9

- This same heptatonic collection can also be interpreted as a G yayue scale in G gong mode ([G, A, B, C-sharp, D, E, F-sharp]), where it builds a major II chord with [A, C-sharp, E] that serves as a subdominant-function chord moving towards the dominant chord with D as the root (Excerpts 2, 3).10

- The A-D-G pentatonic scales are related by ascending fourths, suggesting they are closely related modes with parsimonious voice-leading relationships. The transition from the A major triad [A, C-sharp, E] to the D major triad [D, F-sharp, A] is facilitated by pivoting A from scale degree 1 (gong) to 5 (zhi), with D becoming the new gong.11

- The A-D progression is intrinsic to a “composite pentatonic” collection [A, B, C-sharp, D, E, F-sharp], which is derived from two pentatonic modes. In this case, we can create the set using A gong and A zhi, or A zhi and D zhi.

Li’s theory offers several ways to connect the dominant-tonic function with Han Chinese musical idioms. Additionally, he noted that dominant seventh chords are “particularly Oriental,” suggesting that the dominant-seventh-to-tonic motion is intrinsic to Chinese music expression.

While all three writings contributed to the modernization of Chinese music, the conception of pitch and harmony- regardless of the systems and sources they draw from- is grounded in a twelve-tone equal-tempered system with enharmonic equivalence. As these theories have been taught to generations of composers and widely applied in vast volumes of modern compositions, Chinese music practitioners, including the aforementioned music director and myself, have internalized these harmonic tropes as our native, “traditional” expression.12

Such internalization aligns with Chen Kuan-Hsing’s concept of Internationalist localism, which provides an inspiring framework for reflecting on cultural interplay, particularly the influence of the West on the non-West. As Chen writes:

“The West has been able to enter and generate real impacts in other geographical spaces. […] Rather than being constantly anxious about the question of the West, we can actively acknowledge it as part of the formation of our subjectivity.”13

Through this analytical exercise of the dominant-tonic progression as a Chinese expression, I hope to illustrate that modern Chinese musical expression has internalized many Western musical techniques and transformed them, creating its own distinctive idioms. How we can critically engage with these musical works, which incorporate elements and aesthetics developed from multiple traditions and ideologies, remains an important question and a highly challenging task.

____________

Appendix

Bibliography

Chinese Journal Titles

Liaoning Jiaoyu Gongbao [Liaoning Education Newspaper] 遼寧教育公報

Minzong Jiaoyu Jihan [Journal of Adult Education] 民眾教育季刊

Shidai [Epoch] 時代

Xin Yuechao [The New Music Tide] 新樂潮

Yinyue Jiaoyu [Music Education] 音樂教育

Yinyue Zazhi [Music Magazine] 音樂雜誌

Scholarly Sources

Chen, Kuan-Hsing, Asia as Method: Towards Deimperialization, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Kraus, Richard Curt, Pianos and Politics in China: Middle-Class Ambitions and the Struggle Over Western Music, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Lam, Nathan L., “Pentatonic Xuangong 旋宮 Transformations in Chinese Music,” Music Theory Online 30, no. 1 (March 1, 2024). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.24.30.1/mto.24.30.1.lam.html.

Li, Yinghai, Hanzu Diaoshi Ji Qi Hesheng, Shanghai: Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2001.

Liu, Ching-Chih, A Critical History of New Music in China, translated by Caroline Mason, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010.

Further Reading

Fan, Zuying, Zhongguo Wushengxing Diaoshihesheng Di Lilun Yu Fang Fa, Shanghai: Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2003.

Gao, Jie, Saving the Nation Through Culture: The Folklore Movement in Republican China, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019.

Holm, David, Art and Ideology in Revolutionary China, New York: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Notes

- More specific contexts can be found in chapters 1 and 2 of Liu, Ching-Chih, A Critical History of New Music in China, translated by Caroline Mason (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010). For an understanding of why Western music is read as modern technology and an important tool for Chinese expression, see Richard Curt Kraus, Pianos and Politics in China: Middle-Class Ambitions and the Struggle over Western Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). ↩︎

- The translated harmonic treatise was published in full in Issues 2–4 of Music Magazine (音樂雜誌) Vol. 1, from 1928–1929. Music Magazine was published in 1928–1932 by the Society for the Improvement of Chinese Music (Guoyue gaijin she), of which Liu was one of the founders. The publication used both vertical and horizontal layouts for the texts, with the vertical texts focusing more focused on Chinese musical studies and the horizontal ones on Western classical music. In addition to the harmony texts, Liu published two of his erhu compositions in issue 2, with the score printed in staff notation and his “improved” gongche notation, which adapted the concept of beaming through the use of lines and staff notation. Liu also translated the first two chapters of Prout’s Harmony: It’s Theory and Practice in 1927 for the publication The New Music Tide. ↩︎

- Major scale degrees 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 are translated into gong, shang, jue, zhi, and yu respectively, which is a commonly used Chinese labeling for the pentatonic scale. ↩︎

- Cheng’s original speech was first published in Minzong Jiaoyu Jihan [Journal of Adult Education] in 1930 and was reprinted in Liaoning Jiaoyu Gongbao [Liaoning Education Newspaper] in 1931. An edited version was published in Yinyue Jiaoyu [Music Education] in 1933. ↩︎

- Huang Tzu (黃自, 1904–1938), an influential composer and pedagogue, made this direct comparison in various writings, including “Guoyue and Western Music,” Shidai (1934), 12–13. ↩︎

- Li, Yinghai. Hanzu Diaoshi Ji Qi Hesheng (Shanghai: Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2001), 3. ↩︎

- One of the passages illustrating this view can be found in chapter 11 of the book. It reads (from pp. 113–114), “Pentatonic sonorities do not create much tension or harsh sounds even if we just put a few notes together … for sure it avoids the Western flavor in harmony, but it creates a dull, monotonic harmony with a lack of momentum and potential for development… this cannot be used as the foundational harmonic approach.” (Original text: “只用五聲的結合,隨便幾個音碰在一起也不是太緊張刺耳⋯果然是很容易避免了和聲中的洋味,但是帶來的卻是和聲的單調貧乏,缺乏推動力和開展性⋯這是不能作為基本的和聲手法來應用的”。) ↩︎

- In Li’s explanation, the three forms of heptatonic scales are assigned these names for “historical” reasons, and in the treatise, he mostly replaced the scale names with I, II, and III, respectively. Among the three scales, I and II are more robustly used as the foundation for modal harmonies. ↩︎

- Li stated that such a Dominant-Tonic motion may be out of style if the melody is strictly pentatonic. However, in my experience, using this progression to accompany both pentatonic and heptatonic melodies is quite common. ↩︎

- This major II is seen as identical in harmonic function and voice-leading tendencies to its minor counterpart if we use the qingyue scale to construct the G heptatonic collection, with C-sharp replaced by C. ↩︎

- Li argued that it is a common developmental or modulating process in Chinese pentatonic music. This concept, without Western musical references, has also been theorized as xuangong. Section 2 of Nathan Lam’s recent article in Music Theory Online (MTO) provides a more detailed account of this theory. ↩︎

- Li, Yinghai, Hanzu Diaoshi Ji Qi Hesheng (Shanghai: Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2001), 93-97. ↩︎

- Chen, Kuan-Hsing. Asia as Method: Towards Deimperialization (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 223. ↩︎