[…] Continuation of Part II […]

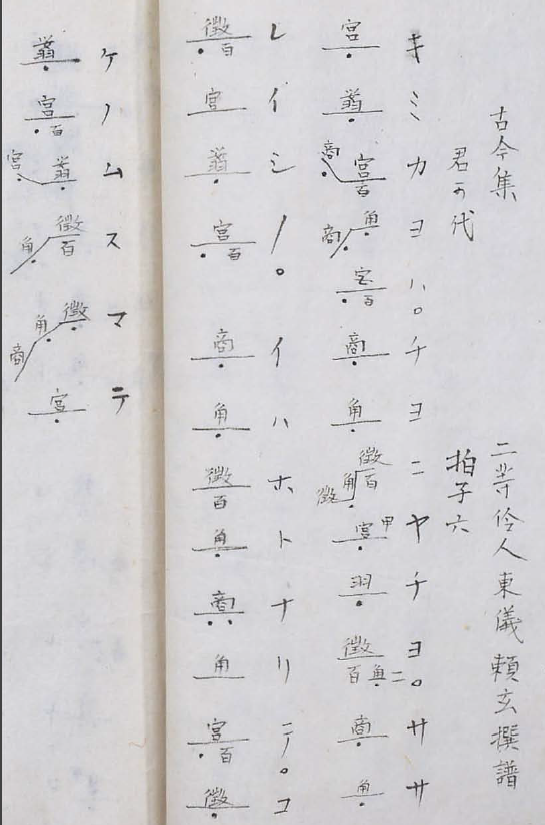

One of the things I find most fascinating about these dynamics I identified in Japanese culture from the time of the Kojiki is that they can also be seen emerging in Japan’s modernizing efforts during the Meiji era (1868–1912 CE). During that period, the wagon, an instrument that had largely been neglected in the musical landscape for about a thousand years, came again into the spotlight as the preferred accompaniment instrument for performances of the songs in the Hoiku shōka, a collection of songs in gagaku style written and compiled for children’s use in schools (see fig. 8).[i]

In the Hoiku shōka we can see three cultural layers clearly: 1) the modern West (especially the Swiss education reformer Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi[ii]) had introduced the notion that teaching children to sing in school was good for their moral character; 2) China had introduced the pair of pentatonic scale types used in these songs, which notably exclude some more indigenously Japanese pitch sets; and 3) Japan itself provided both the song texts and the musical accompaniment entrusted to the wagon, which could be seen to represent a quietly unshakable backdrop to all of these foreign influences, refusing to have its notes ordered by height like a piano or a qín (let’s remember here that, as I showed in the previous blog post, the wagon places its bridges in a zigzag pattern, creating strings of alternating lowness and highness). The Hoiku shōka resembles the Kinkafu in more than a few ways, making it perhaps no surprise that the Kinkafu’s manuscript was published in handsome facsimile for the first time in 1927 (without which my own current research on it would have been impossible or much more difficult). By 1927 the Hoiku shōka had long since lost the battle over childhood singing education,[iii] but an interest in unearthing and studying the spirit that had informed it, that spirit that so enthusiastically imported foreign influences as a tool for presenting native (or native-coded) material, remained.

Japan’s position relative to China and its other neighbors of course changed radically very soon after the Meiji Restoration, and by the time this facsimile of the Kinkafu was published in 1927, China’s Qing Dynasty was already fifteen years dead, and the Republic of China, in the midst of its own turbulent process of self-reinvention with which Japan would soon heavily interfere, was debating how many Japanese loan words it should accept into its language[iv]—in other words, the power dynamic between Japan and China had reversed for the first time in history. Much of the Japanese interest from this period in Japan’s own ancient music and writings is, from our current vantage point, almost impossible to read separately from Japan’s imperialist ambition. The conquest of foreign lands had already started and would soon increase a hundredfold, making the Kinkafu’s lovely facsimile and its intriguing relationship to the Hoiku shōka hard to appreciate in an entirely detached way. Such detachment, however, need not be the goal.

Rather, I propose a longer historical view that takes into account the different valences that “native Japanese” versus “foreign” identity markers have had throughout many different points in time. Doing so can help us understand each document in a variety of sometimes-contrasting contexts all at once: that the Kinkafu has been, at different times, both a push against linguistic and cultural subjugation by China; and, much later, a push towards subjugating China and other Asian cultures. The same could be noted about the Kojiki god’s order for Emperor Chūai to conquer Shilla, from which even his zither-playing could not save him. In its own time, that story seems to have been a harmless power fantasy of Japan (a weaker, less literate, and less nationally-defined land) against the powerful Chinese-allied Korean kingdom of Shilla. But in the twentieth-century, more than a thousand years later, it became a tool of propaganda to justify Japan’s occupation of Korea: Japan annexed Korea in 1910, holding it until the end of World War II in 1945. During this time, aggressive suppression of Korean culture and language was sometimes rationalized as simply the continuation of the campaign supposedly led by Empress Consort Jingū, Chūai’s widow, after his zither-accompanied death in 200 CE.[v] The scars of this period of occupation still have not healed in our current day, and a deeper understanding of the tiny supporting roles played by zithers and their notation will probably not be the thing that heals them. But it has at least kept me aware of just how easily artworks and their symbolic languages can be turned to purposes completely alien to their original circumstances, and remaining aware of that has helped me find a way to approach these works responsibly while also re-learning to enjoy them as stories and music.

Bibliography

Primary sources, in manuscript facsimile (all visible in at https://www.ndl.go.jp)

Kojiki 古事記 (712)

Nihon Shoki 日本書紀 (720)

Kinkafu 琴歌譜 (981, reprinted 1927)

Kojiki-den 古事記伝, by Motoori Norinaga 本居宣長 (1798)

Modern scholarship

Brannen, Noah. 1968. “Ancient Japanese Songs from The Kinkafu Collection.” Monumenta Nipponica 23 (3/4): 275–320.

Eppstein, Ury. 1985. “Musical Instruction in Meiji Education: A Study of Adaptation and Assimilation.” Monumenta Nipponica 40 (1): 1–37.

Gottschewski, Hermann. 2003. “Hoiku shōka and the Melody of the Japanese National Anthem Kimi ga yo.”東洋音楽研究 [Research on eastern music] 68: 1–17, 23–24.

Huang Ko-Wu 黄克武. 2008. 新名詞之戰 [The battle over new nouns]. 中央研究院近代史 研究所集刊 [Academia Sinica modern history research collected papers] 62: 1–42.

Koizumi Fumio 小泉文夫. (1958) 1977. 日本傳統音楽研究 [Research on Japanese traditional music], 10th printing. Tokyo: Ongaku no Tomo Sha.

Maeda Akira 前田晁. 1933. 少年国史物語 [Stories of our nation’s history for young boys]. Tokyo: Waseda University Press. Transcription with translation into modern Japanese at http://jpn-hi-story.la.coocan.jp/

Manabe, Noriko. 2009. “Western Music in Japan: The Evolution of Styles in Children’s Songs, Hip-Hop, and Other Genres.” PhD diss., City University of New York.

Masuda Osamu 増田修. 1999. 『琴歌譜』に記された楽譜の解読と和琴の祖型 [Reading the musical notation recorded in the Kinkafu and the prototype of the wagon]. http://www.furutasigaku.jp/jfuruta/simin11/kinkafu.html.

Philippi, Donald (translator). 1968. Kojiki. Tokyo: Princeton University Press and University of Tokyo Press.

Suzuki Seiko 鈴木聖子. 2014. 「科学」としての日本音楽研究:田辺尚雄の雅楽研究と日本音楽史の構築 [Japanese music research as “science”: Tanabe Hisao’s gagaku research and the construction of Japanese music history]. PhD diss., Tokyo University.

[i] See Gottschewski passim and Manabe 82–96 for more on the Hoiku shōka.

[ii] Suzuki 180.

[iii] Specifically, it lost the battle to Isawa Shūji—for more, see Manabe 98–136 and Eppstein passim.

[iv] Huang passim.

[v] For example, the Shōnen kokushi monogatari 少年国史物語 (“Stories of our nation’s history for young boys”), a set of historical narratives written for children by one Maeda Akira 前田晁 and published in the 1930s, features in its first volume, the story of Jingū’s conquest of Shilla. It ends with a brief section bearing the rather innocuous heading “Relations between our country and Korea,” which brings the tale’s ancient matter into the present by explaining that after Jingū’s conquest of the Korean peninsula, “There were various changes, and once they had cut off this close relationship, Korea became a separate nation and stood independently, but when it became Meiji [1868–1912 CE], it was again merged with our country. In other words, it returned to the distant past, and again became the way it originally was.”