Prof. Long’s recent observations on hexachordal solmization raise several issues that cannot be fully teased out in blog format. The one overarching question I would like to pose for an initial response is the following: I have no doubt that solmization “just makes sense” as a method for singing Renaissance polyphony, and that it has changed Prof. Long’s understanding of Renaissance polyphony substantially. But why is it so, precisely? Which mechanism(s) or musical relationships does solmization trigger in the mind that wouldn’t otherwise surface? I suggest that solmization works not because it mirrors the hexachordal structure of the music, but rather because it highlights the affinity of the diatonic pitches at the fourth and at the fifth in a heptachordal, two-semitone universe—Guido’s rationale for introducing the syllables to begin with.[1] The very notion that Western music of the pre-modern era was hexachordally-coded (often tacitly assumed when not explicitly stated) is not easily reconciled with the observation that both the modal system (no matter which one) and the grammar of counterpoint unquestionably assumed the octave as the basic yardstick, to which the hexachord could only take second seat. Thus, the “mental map of musical space” that we may newly construct after re-familiarizing ourselves with Guido’s method is unlikely to be a hexachordal one, as Prof. Long appears to suggest throughout her blog. The practice of solmization itself points to such a conclusion: singing all semitones as mi-fa will not and should not erase the aural recognition of the different positions of the diatonic semitones within the modal octave, appropriately marked by the different litterae E-F and B-C (or A-Bb). More importantly, hexachords do not reflect pitch hierarchies, which are key to marking the beginning and the end of diatonic segments, especially those claiming structural priority: the same pitch will often fall on two different syllables, just as the same syllable will often indicate different pitches. In fact, since the hexachords overlap with one another, it is virtually impossible to tell where one ends and where the next begins.

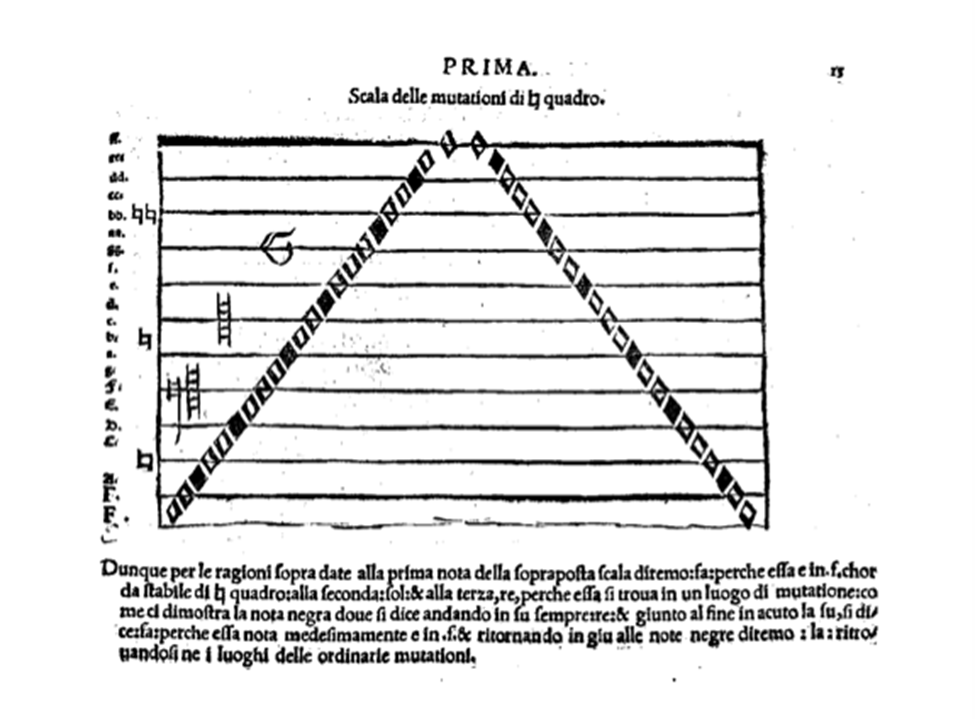

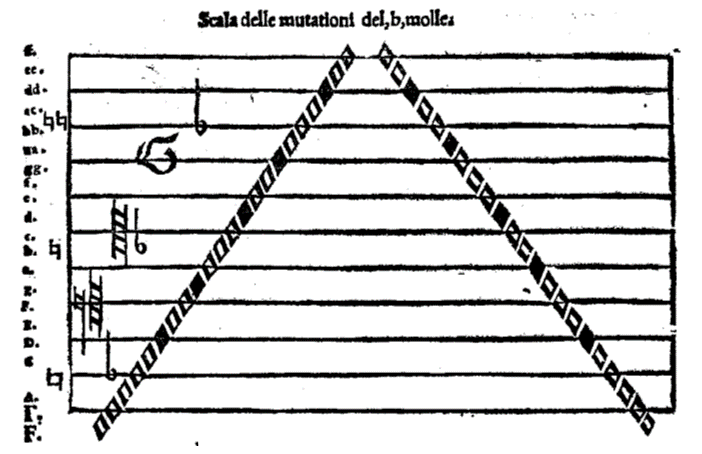

In Giovanni Maria Lanfranco’s Scintille di musica cited by Prof. Long (Lanfranco 1533), the two lambda-shaped graphs of the “Scala delle mutationi di be quadro” and “del be molle”complicate author’s own reference to “sounds conceived in the mind by means of the six singable syllables”[2] (see Figs. 1 and 2 below):

Translation of the caption: “For the reasons given above, on the first [lowest] note of the scale we will say ‘fa’ because it falls on F, a ‘stable’ pitch of the ‘Scala di be quadro.’[3] On the second we will say ‘sol’ and on the third ‘re’ because it coincides with a point of mutation, as shown by the black note, which will always correspond to ‘re’ when ascending. On the highest note one says ‘fa’ because it is also on F. When descending we will say ‘la’ on the black notes, as they are found in the places of regular mutations.”

To begin, in response to an important point in Prof. Long’s blog, these graphs point to the two Scale as mutually exclusive, confirming Lanfranco’s heptachordal conception of diatonic space despite his own wording elsewhere in the treatise. More specifically, such diagrams provide a different angle into Renaissance notions of diatonic space than the more familiar genre of introductory gamuts (such as the one from Gumpelzhaimer’s Compendium musicae, shown at the end of Prof. Long’s blog, or the one from Lanfranco 1533, p. 6), in that they show the actual yoking of letters and syllables in the fray, rather than as abstract sets placed in different portions of the graph. Even though there are no actual syllables in the two graphs, we may surmise that singers would have superimposed them onto the ladder more or less in line with Lanfranco’s instructions: that is to say, by singing every black note as re going up and as la going down, and by properly “deducing” the syllables of the other notes, the scala will be intoned with the correct sequence of tones and semitones (this should not suggest that the syllables are needed to achieve that result). One notable point here is that ut, often described as the root of each hexachord,[4] is never actually used in the Scala di be quadro and is deployed only on the lowest F of the Scala del be molle. Furthermore, it is important to realize that the black notes punctuate the ladder alternatively after four and five notes—a “limping” pace that by itself betrays the primacy of the octave and its asymmetrical internal division into a tetrachord and a pentachord.[5] Regular periodicity occurs only in seven-note cycles (as in G-re and g-re, or a-la and A-la).

Thus, Lanfranco’s singer is invited to rely on a transposable set of six syllables to cover the entire diatonic terrain, but since the necessary mutations take place every four or five notes, those are the de facto audible segments of musical space that for better or worse impact musical experience. It would be a stretch, in my view, to imagine that Renaissance singers (let alone listeners) would have inferred the rest of the hexachord when singing only portions of them in practice. One might well infer la of the old hexachord when singing re of the new one, but what about the ut below that new re? What would be the musical import of such hexachordal inferences, anyway? Furthermore, the fact that one almost never touches the outer pitches of the hexachord going up (ut and la), while stepping repeatedly on la on the way back, appears to be entirely non-consequential. In short: Lanfranco’s graphs show that the syllabic hexachords populating the standard medieval and Renaissance gamuts do not play a role qua hexachords, and are not meant to be audible as such; rather, they are comparable to identical pieces of raw fabric to be cut up and partly discarded in order to fit a pre-determined shape.

For a more plausible insight into the kind of hearing promoted by solmization we may turn to Guido’s notion of affinitas: according to that key doctrine, Dis similar to A in that they both have the same sequence of tones and semitones above (TSTT), though they differ on the quality of the third below (minor for D, major for A in the “Scala di be quadro”). Thus, they may be both labeled re for sight-singing purposes, and marked with the same black note in the graphs of mutations, though they ultimately have different positions within the uneven portions of fourths and fifths in those same graphs. Only pitches in the same position in the 7-note wheel (D-re/d-re or A-re/a-re) are diatonically identical, which is why they are labeled with the same littera AND syllable. So, when singing a D protus melody it is surely revealing, and even music-analytically interesting, to place la on both D and A as the occasion demands it: the solmization has cognitive significance in that it highlights the close diatonic relationship of those two pitches within the octave, so close indeed that A was regarded as a viable protus ending. Similarly, Guido’s method draws attention to the same relationship of affinitas at the fourth or fifth between the other pairs of pitches in the gamut.

One should be weary of generalizing too broadly after looking at one graph, of course. Yet, in my view there is significant evidence elsewhere suggesting that the placement of the ut-la segments on litterae a fourth or fifth apart (beginning on F, C, and G) was more consequential for medieval and Renaissance musicians, and more revealing of how a brain on hexachordal solmization actually functions, than the mere size of those segments.

REFERENCES

Babb, Warren, transl. 1978. Hucbald, Guido, and John. Three Medieval Treatises, ed. C. Palisca. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Baragwanath, Nicholas. 2020. The Solfeggio Tradition: A Forgotten Art of Melody in the Long Eighteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lanfranco, Giovanni Maria. 1533. Scintille di musica. Brescia: Lodovico Britannico.

Mengozzi, Stefano. 2010. The Renaissance Reform of Medieval Music Theory: Guido of Arezzo Between Myth and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[1] See Mengozzi 2010, pp. 30-34 on this point. Although Guido does not explicitly link his solmization system to the theory of the affinities, in Micrologus he identifies the major sixth as the common modus vocis between pairs of pitches at the fourth or fifth (Babb 1988, pp. 63-64). The doctrine of affinitas takes center stage also in the final portion of the Epistola ad Michahelem.

[2] “… i suoni nella mente concetti per mezzo delle sei sillabe cantabili,” (Lanfranco 1533, p. 16).

[3] A “stable” pitch for Lanfranco is yoked to only one syllable; thus, F is “stable” in the “Scala di quadro,” where it can only correspond to “fa” (Scintille di musica, p. 12).

[4] “… le note sono sei, cioè ut re mi fa sol la, sette volte ritornate e governandosi le cinque dallo ut, che per se stesso si governa e regge” (Lanfranco 1533, p. 9).

[5] Late-18th-century Italian solfeggio treatises still speak of mutazioni di quarta and di quinta (Baragwanath 2020, 72-73).