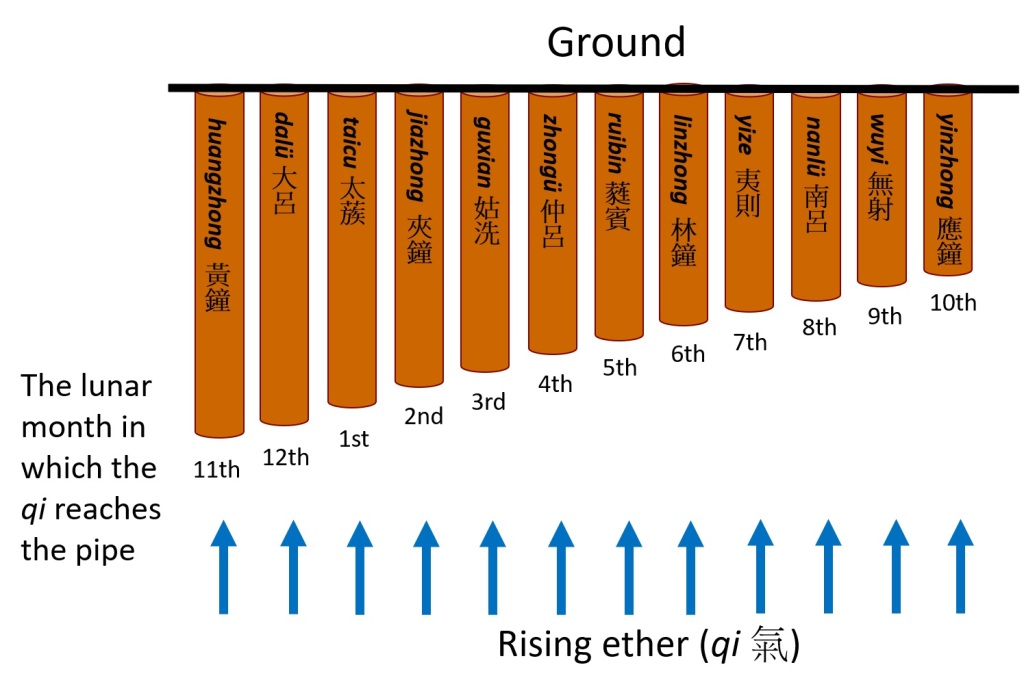

In 1672, on the twelfth day of the eighth month of the eleventh year of the Kangxi reign (r. 1662–1722), the emperor issued an edict abolishing a practice of musico-cosmological observations, known as houqi, which lasted for more than a thousand years in China: “The method of houqi has long been lost. It is hardly credible and reliable.”[1] Before the practice was abolished, it had been performed to detect the annual arrival of the vernal equinox (chunfen 春分) in the second lunar month by the Astronomical Bureau. Translated as “watching the ether,” houqi 候氣 involves filling with reed ashes twelve pitch-pipes (lüguan 律管), each producing one pitch of a chromatic scale, then burying them in the soil. It was believed that at each of the twelve major solar terms (e.g., the equinoxes and solstices) in each month, the ashes inside the corresponding pitch-pipe would be blown forth from below owing to the movement of qi 氣 (commonly translated as “ether” or “vital force”) pertaining to the solar term (Figure 1).[2] For instance, the ashes inside the reference pitch pipe of huangzhong 黃鐘—akin to the Western middle C—would be blown forth from below at the winter solstice in the eleventh lunar month.

Although failed attempts to obtain valid and reliable results had cast doubt on the theory of houqi, the practice had been sustained for more than a thousand years. Existing studies tend to attribute the practice’s longevity to fraudulent procedures, fabricated reports, ad hoc explanations for inconsistent results, and its conformity to the Chinese correlative worldview.[3] By invoking Harry Collins’s concept of the “experimenters’ regress,” however, I would like to shift focus towards the nature of houqi as an experiment. An experiment is not just an empirical method to test a theory, but also a skillful practice whose validity is also subject to test. Rather than emphasizing the impossibility of verifying the houqi theory, I shall highlight the difficulty in falsifying it owing to the very nature of experiments. But before that, let’s retrace the history of the houqi practice and of the attempts to verify it.

The earliest detailed account of houqi is found in the Book of the Later Han (Hou Han shu 後漢書; Later Han: 25–220), where it is proposed as a method of tuning rather than of cosmological observation:

[Zhang Guang and his colleagues] could not determine the tensions [huanji, literally “slow and fast”] of the strings [of Jing Fang’s thirteen-string tuner]. Pitches cannot be written down and shown to others. Those who know [the pitches] do not have the means to teach about them even if they want to. Those who understand [the pitches] with their mind-hearts learnt about them through experience, not from a teacher. Therefore, official historians who could identify pitches became extinct. Only the approximate numerical values [of the pitches] and houqi could be transmitted.[4]

The reliance on houqi in determining an appropriate pitch standard arose from the difficulty in documenting absolute pitches without the knowledge of sound frequency. Although there were plenty of documents that recorded the length and diameter of the pitch-pipe generating the reference pitch huangzhong, it was difficult to obtain the actual dimensions without knowing the measurement standard. In the absence of a consistent measurement standard across different regimes and regions or a means to translate between different measurement systems, pitch standard could not be transported on papers. In other words, they could not be transformed into what Bruno Latour calls “immutable mobiles,” like the positions of the planets marked on a star chart, or the locations of places represented on a map.[5]

While it is uncertain whether the account on houqi in the Book of the Later Han was meant to be a report of an actual experiment or a description of the procedures and predicted results, the Book of Sui (Sui shu 隋書) did document some actual attempts. Whereas Xin Dufang 信都芳, a staff officer in the Northern Qi (550–577 CE), successfully observed the scattering of ashes from his pitch-pipes at the corresponding solar terms, Mao Shuang 毛爽 (fl. 589 CE), the mayor of Shanyang 山陽, together with his colleagues from the Ministry of Music, obtained irregular results from their observations in 589 CE: the ashes sometimes scattered early, sometimes late, sometimes in abundance, sometimes in scarcity. When asked by Emperor Wen of Sui 隋文帝 (r. 581–604 CE) for an explanation, Niu Hong 牛弘 (545–610 CE) associated the volume of scattered ashes with the quality of governance: when half of the ashes were blown forth, it indicated that there was good governance; when all of the ashes were blown forth, it indicated that the officials were too relaxed; when no ashes were blown off in response to the movement of qi, it indicated that the emperor was atrocious. On the ground that it was impossible for the state of governance to vary from month to month, the emperor rejected Niu’s explanation and asked Mao for a report. In his report, Mao mentioned the music minister Du Kui’s 杜夔 (fl. 188–226 CE) failure in “watching the ether” and Xun Xu’s 荀勗 (ca. 221–289 CE) identification of its reason. Xun compared an ancient bronze ruler with Du’s ruler and found that it was 4 fen 分 shorter than Du’s, concluding that Du’s failure in houqi was due to the wrong dimensions of his pitch-pipes.[6] Mao also mentioned that his ancestor Mao Qicheng 毛栖誠 (fl. 502 CE) succeeded in houqi only after he modelled his pitch-pipes on a jade pitch-pipe acquired from a tomb in Ji 汲 (near present-day Weihui 衛輝 in Henan).[7]

Rather than providing an ad hoc interpretation as Niu Hong did, houqi experimenters tended more often to attribute negative or inconsistent results to flaws in the procedures and apparatus. According to Li Shida 李世達 (1533–1599), the Ming prime minister Zhang Juzheng 張居正 (1525–1582) also attempted to watch the ethers to no avail, but succeeded after he had modified the procedures following Yuan Huang’s 袁黃 (1533–1606) advice, which includes adjusting the depth and thickness of the chamber walls, the directions in which the doors of the three chambers face, and the length ratios of the pitch-pipes.[8] Yuan’s advice filled in a lot of gaps in the procedures described in the Book of the Later Han, which consists of only forty-nine characters. Although it is stipulated—probably to prevent winds from affecting the results—that the pitch-pipes should be placed inside three layers of chambers with airtight doors and hung with reddish silk fabrics, there are no specifications with respect to the sizes of the chambers, the directions of the doors, etc. It is instructed that the twelve pitch-pipes, each supported by a wooden rack, should be placed at the corresponding directions, but the directions are not specified.[9] Yet even if these variables are stated, it is still difficult to reproduce the procedures from a written record, for there are always more gaps to be filled. Some experimenters even contested on the place of origin of the reed ash, that of the bamboos used to make the pitch-pipes, and that of the millet grains used to measure the volumes of the pitch-pipes.[10]

[1] 至飛灰候氣,法久不傳,難以憑信。Shengzu Ren huangdi shilu 聖祖仁皇帝實錄 [Veritable Records of the Kangxi Emperor] (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1986), 39.26a.

[2] In the Chinese lunisolar calendar, a solar year is divided into four seasons (ji 季), further divided into twelve major solar terms (jie 節) and then twenty-four solar terms (qi 氣). The twenty-four solar terms are 15 degrees apart in terms of the ecliptic longitude of the sun, with the major and minor solar terms alternating with one another. The twelve major solar terms are vernal equinox (0°), grain rain (30°), grain buds (60°), summer solstice (90°), great heat (120°), end of heat (150°), autumn equinox (180°), frost (210°), light snow (240°), winter solstice (270°), severe cold (300°), and spring showers (330°), where the vernal equinox (0°), summer solstice (90°), autumn equinox (180°), and winter solstice (270°) mark the beginning of the four seasons respectively. There are usually a major solar term and a minor solar term in each lunar month, but in about every thirty months, there is a month in which there is no major solar term owing to the incomensurability between the solar and lunar cycles. That month is treated as an intercalary month.

[3] Derk Bodde, “The Chinese Cosmic Magic Known as Watching for the Ethers (1959),” in Essays on Chinese Civilization, ed. Charles Le Blanc and Dorothy Borei (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 351–372; Yi-Long Huang and Chih-ch’eng Chang, “The Evolution and Decline of the Ancient Chinese Practice of Watching for the Ethers,” East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine 13, no. 1 (1996): 82–106; Dai Nianzu, Zhongguo shengxue shi 中國聲學史 [A History of Acoustics in China] (Shijiazhuang Shi: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe, 1994), 503.

[4] ……猶不可定其弦緩急。音不可書以時[曉]人,知之者欲教而無從,心達者體知而無師,故史官能辨清濁者遂絕。其可以相傳者,唯大搉常數及候氣而已。 Fan Ye and Sima Biao, Hou Han shu 後漢書 [Book of the Eastern Han], vol. 11 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1965), 3015.

[5] Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 227–229.

[6] In Ancient China the length of a ruler represented the length of 1 chi 尺, which was subdivided into 100 fen 分. The exact lengths of these measuring units varied in different dynasties according to the measuring standard. In Xun Xu’s time, 1 chi was approximately 25 cm.

[7] Fan Ye and Sima Biao, Hou Han shu, vol. 11, 3016; Wei Zheng, Sui shu 隋書 [Book of Sui] (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1973), 394–396.

[8] Bodde, “The Chinese Cosmic Magic,” 33–34.

[9] Fan Ye and Sima Biao, Hou Han shu, vol. 11.

[10] Huang and Chang, “The Evolution and Decline of the Ancient Chinese Practice of Watching for the Ethers,” 85.

[…] Continuation: Part II […]