Davide Daolmi

(English Translation: Giulia Accornero)

[…] Continuation of: Part I

As we have seen in Part I, the differences between SqA to SqB reveal the adoption of a different divisio to convey different tempi in proportional relation to a stable tactus. The function of this notational device will later develop into what is known as cut time (¤ ¢). In effect, if one compares the use of Italian and Gallic divisiones as presented in the Rubrice with the modern concept of integer valor, then the tempi minores and minimi are equivalent to the cut time (diminutum).[1] That the metrical solutions achieved through the system of divisions were maintained in white mensural notation, should not come as a surprise since the shift from black to white notation was of an exclusively graphic nature.

In this second part of the post, based on the Rubrice, I suggest that in the first half of the fourteenth century the Italian system adopted a tactus that was faster than that of France, and which, slowing down in the second half of the century, came to be adapted to the prevailing French model.

In other words, if Marchetto’s Pomerium presents Bs of different values only in relation to their perfection or imperfection, later, the Rubrice provide the means to adapt the tactus to both the S and the B as well as offers two tactus, i.e. an Italian one and a slightly slower French one.

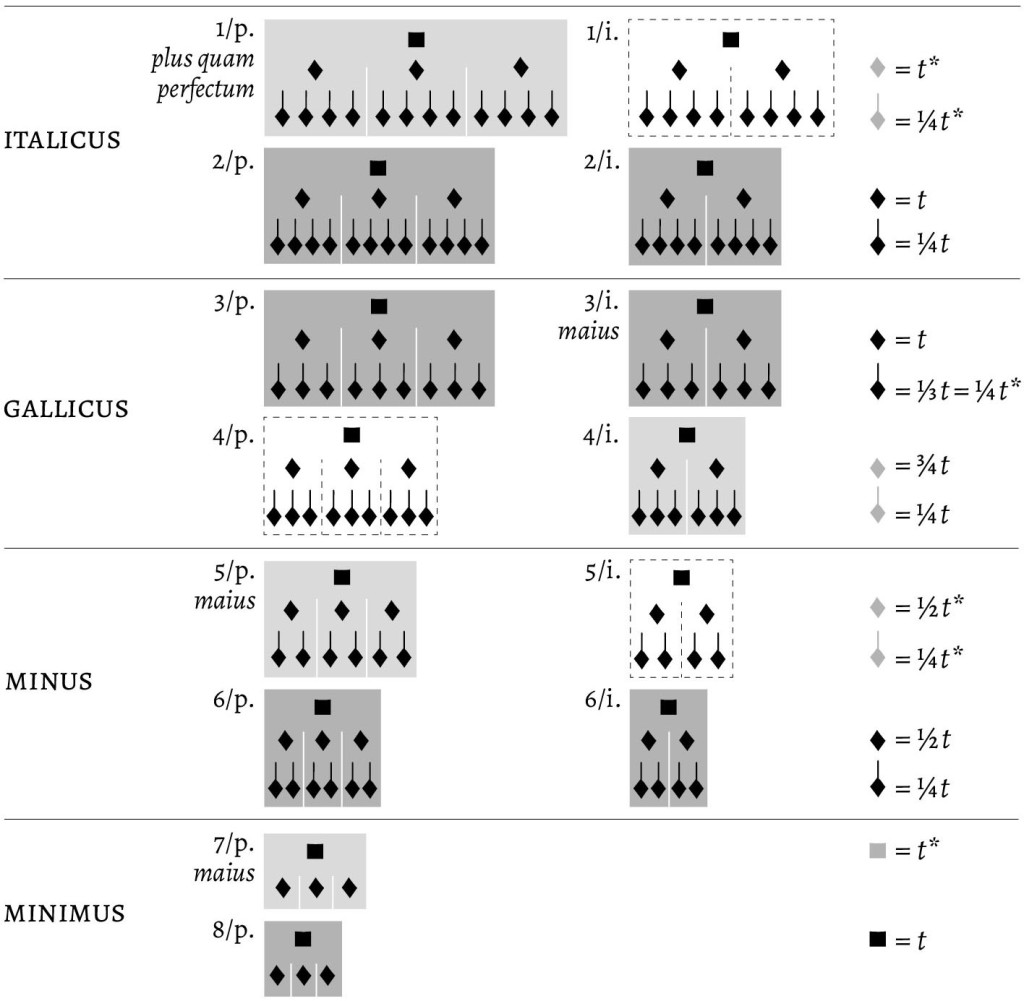

The Rubrice, as observed by Gozzi 2001, provide an varied range of tempi that could be summarized as follows (t = tactus italico, t* = tactus gallico): [2]

Come spiegato nella prima parte, la trasformazione da SqA a SqB rivela l’adozione di una diversa divisio al fine di comunicare l’uso di diversi tempi in relazione proporzionale ad un tactus stabile. La funzione di questo espediente notazionale verrà in seguito assorbito dall’uso del tempo tagliato (¤ ¢). In pratica se alle divisiones italiche e galliche delle Rubrice si associa il moderno concetto di integer valor, i tempi minores e minimi trovano corrispondenza in quello che poi sarà il tempo tagliato (diminutum).[1] Questa anticipazione di soluzioni metriche che apparterranno poi al mensuralismo bianco non deve stupire: il passaggio da notazione nera a bianca fu una trasformazione esclusivamente grafica, e sarebbe stato poco probabile che princìpi così importanti come i rapporti fra durate venissero abbandonati.

Sulla base delle Rubrice si può fare un passo ulteriore e ipotizzare che il sistema italiano gestisse nel primo Trecento un tactus più rapido di quello francese, per poi subire un rallentamento nella seconda metà del Trecento allo scopo di adeguarsi al modello francese dominante.

In pratica se con Marchetto le diverse durate fra B sembrano riguardare solo il rapporto perfetta/imperfetta, in seguito con le Rubrice non solo si esplicita la possibilità di adattare il tactus sia alla S, sia alla B, ma si propone un doppio tactus di durata lievemente differente, dove quello francese è un po’ più rallentato.

Le Rubrice infatti, come ha notato Gozzi 2001, propongono una casistica assai articolata dei tempi di esecuzione che può essere così sintetizzata (t = tactus italico, t* = tactus gallico): [2]

In the above table, the dark grey background indicates that the division had already been identified by Gallo (1966/a: 61-63.) In addition to drawing up the propositional relationship between the Italian divisiones, the Rubrice offer an alternative tactus, termed rariora (here presented on light-gray background). While Gozzi (2001) has already drawn attention to the presence of a double tactus, I disagree with his claim that the adjective rarius stands for “sparse,” “infrequent”—that is, slower. In fact, since the term denotes the faster variation of the senaria imperfecta (4/i), it should be understood in its common sense of “less frequently used”.[3] It is likely that the options termed rariora were used on occasion, only for certain musical genres.

(Where the divisions are framed by a dashed line, this is based on my own conjecture; they were not mentioned in the Rubrice, possibly because they were not in use.)

What I find particularly revealing in the Rubrice is the presence of two different tactus based on the speed of the Ms, as showed in the above table. The Italian system featured a uniform articulation of 4 Ms while the French system relied on a 3 Ms articulation, possibly used to provide a slower alternative.

In the Rubrice, these two types of tactus, in which the Ms stand in sesquitertian proportion (that is t e t*), appears to be an attempt to compare local Italian practice with that imported from France. Given that the French tactus was based on the rate of the pulse (ideally t* = 72-80 bpm), we can assume that the Italian tactus would have had a pace of 96-106 bpm. We cannot determine, however, if and how these notational options shaped performance.

Although the French model would come to prevail by the end of the Trecento, most of the music in Italian notation, especially from mid-Trecento, seems better suited to a faster tempo. Ita se n’era, despite the use of extremely small values, also requires a quicker tactus.[4] (This would also corroborate its proposed date of composition, i.e. mid-Trecento.) It is therefore inappropriate to slow down the tactus to better accommodate the smaller values introduced by Lorenzo. This notation, in fact, might have been devised so as to record the extemporaneous embellishments of professional singers, which required a rapid execution to avoid ponderous phrasing.

Perhaps the reasons why Lorenzo’s solution was doomed to fail rests in his aspiration to write what, at that time, belonged to singers’ improvising ability and could work only in certain specific performative circumstances. Only a few decades later, however, the ars subtilior would again attempt to adapt the notation to express ornamental melodic passages.[5] Nevertheless, Lorenzo’s attempt opens a window onto mid-Trecento improvising practice. It confirms that singers used to introduce diminutions also in polyphonic practice and lends credence to the theory that the principles of tactus were already part of performance practice.

[1] While it is true that the two “devices” do not map perfectly onto each other, tactus theory has been ambiguous ever since its first formulations. In many treatises cut time is not simply a tactus doubled in speed (the beat alla breve), but rather an indication of acceleratio mensure (DeFord 2015: 126).

[2] I provide a detailed examination of the Rubrice—a synoptical edition based on the three extant manuscripts and a critical commentary—at www.examenapium.it/rubrice.

[3] The difference between my table and Gozzi’s are limited to the senaria perfecta. For details, see the online edition mentioned in the previous footnote.

[4] While we cannot rely on one performance for statistical significance, the ensemble Platino87 has recorded the madrigal Ita se n’era in the Cd La bella mandorla (Cpo, Köln 2012) adopting a metronome marking of approximately 108 beats per minute.

[5] «The resultant manuscript represents a ‘finished’ version, but there remains the possibility that it may have further and alternatively decorated by performers» (Greig 2003: 202).

Le Rubrice, oltre a mettere in proporzione le divisiones italiche (quelle su fondino grigio scuro già individuate in Gallo 1966/a: 61-63), descrivono anche soluzioni alternative, dette rariora, con tactus differente (fondino grigio chiaro). Gozzi (2001) aveva messo a fuoco quest’aspetto del doppio tactus, tuttavia interpretava l’aggettivo rarius con significato di ‘rado, diradato’, cioè più lento. Dal momento però che il termine identifica anche la variante più rapida della senaria imperfetta (4/i.) deve necessariamente esser inteso nel suo significato comune di ‘usato meno di frequente’.[3] Con tutta probabilità, le forme rariora erano occasionali e si usavano solo per alcuni generi musicali.

Le Rubrice non parlano delle forme che nello schema ho riquadrato con un tratteggio probabilmente perché non erano praticate (qui le propongo congetturalmente per completare lo schema).

Il dato tuttavia interessante è che lo schema mostra chiaramente come scaturiscano due diversi tactus legati alla velocità della M. Sulla base di una scansione uniforme il sistema italiano ne accoglieva generalmente 4, mentre l’andamento a 3M delle forme galliche poteva essere utilizzato per creare un’alternativa più lenta.

Questo doppio livello di M con due tipi di tactus in proporzione sesquiterza (t e t*), sembra un tentativo delle Rubrice di mettere in relazione la pratica locale (italica) con quella d’importazione francese. Dal momento che il tactus francese sarà associato alla pulsazione sanguigna (idealmente t* = 72-80 bpm) possiamo assumere che il tactus italiano fosse attorno ai 96-106 bpm. Evidentelemte è difficile dire quanto questo principio fosse realmente applicato nella pratica.

Sebben dalla fine del secolo sarà il modello francese a prevalere, tutta la musica in notazione italiana, almeno quella di medio Trecento, sembra preferire un ritmo più spigliato di quella francese. Anche Ita se n’era, malgrado l’uso di valori piccolissimi, richiede un tactus rapido,[4] e questo conferma la data di composizione attestata vicina alla metà del secolo. Inopportuno quindi rallentare il tactus per gestire meglio i nuovi valori introdotti da Lorenzo. Si tratta infatti di una forma di notazione che sembra voler restituire quelli che erano gli abbellimenti estemporanei del cantore professionista, passaggi che pertanto richiedono un’esecuzione rapida, necessaria per non rendere estenuato l’intero madrigale.

Le ragioni per cui la soluzione di Lorenzo non ebbe successo è perché forse pretese scrivere ciò che in quel momento apparteneva all’abilità dell’improvvisazione e poteva funzionare solo in specifiche circostanze performative (solo qualche decennio dopo l’ars subtilior tenterà anch’essa di piegare la notazione a prescrivere forme ornamentali della melodia).[5] Il fallimento di Lorenzo apre uno spiraglio sulla pratica improvvisativa di metà Trecento, non solo confermando un’ovvietà, ovvero che i cantanti amavano introdurre diminuzioni anche nella pratica polifonica, ma rendendo concreta l’ipotesi che i principi del tactus erano, nella pratica, già normalmente adottati.

[1] La corrispondenza non è puntuale, ma del resto la teoria del tactus, fin dalle prime formulazioni, rimane incerta. Il tempo tagliato, in molti trattati, non è semplicemente un tactus di velocità doppia (poi battuto alla breve), ma un’indicazione di acceleratio mensure (DeFord 2015: 126).

[2] Propongo una disamina dettagliata dell’intero testo delle Rubrice, con l’edizione sinottica dei tre testimoni e un commento critico, alla pagina www.examenapium.it/rubrice.

[3] Le differenze fra il mio schema e quello di Gozzi, in realtà limitate solo alla senaria imperfetta, sono esplicitate nell’edizione on line segnalata alla nota precedente.

[4] Per quanto sia significativa una sola esecuzione, l’unica in questo momento, l’ensemble Platino 87 ha inciso il madrigale nel Cd La bella mandorla (Cpo, Köln 2012) adottando un metronomo vicino a 108.

[5] «The resultant manuscript represents a ‘finished’ version, but there remains the possibility that it may have further and alternatively decorated by performers» (Greig 2003: 202).

Bibliographical References

Apel 1942

Willi Apel, The notation of polyphonic music: 900-1600, Cambridge ms: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1942, 61961, trad. it. Firenze: Sansoni, 1984.

Bonge 1982

Dale Bonge, Gaffurius on pulse and tempo: A reinterpretation, «Musica disciplina», 36 (1982), pp. 167–74.

DeFord 2015

Ruth I. DeFord, Tactus, mensuration, and rhythm in Renaissance music, Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2015.

Gaffurio 1496

Franchino Gaffurio, Practica musice, Mediolani: Ioannis Petri de Lomatio, 1496; trad. it. ed. Paolo Vittorelli, Firenze: Galluzzo, 2017.

Gallo 1966/a

F. Alberto Gallo, La teoria della notazione in Italia dalla fine del xiii all’inizio del xiv secolo, Bologna: Tamari, 1966.

—— 1966/b

Mensurabilis musicae tractatuli, ed. F. Alberto Gallo, Bologna: Amis, 1966.

Gehring-Huck 2004

Julia Gehring, Oliver Huck, La notazione italiana del trecento, «Rivista Italiana di Musicologia», 39/2 (2004), pp. 235-270.

Gozzi 1995

Marco Gozzi, La cosiddotta ‘Longanotation’: Nuove prospettive sulla notazione italiana del Trecento, «Musica disciplina», 49 (1995), pp. 121-149.

—— 2001

Marco Gozzi, New light on Italian Trecento notation, «Recercare», 13 (2001), pp. 5-78.

Greig 2003

Donald Greig, Ars Subtilior repertory as performance palimsest, «Early Music», May 2003, pp. 197-209.

Sairisi 1975

Nancy G. Siraisi, “The Music of Pulse in the Writings of Italian Academic Physicians (Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries)”, Speculum, 50/4 (1975): 689-710.

Sartori 1938

Claudio Sartori, La notazione italiana del Trecento in una redazione inedita del ‘Tractatus practice cantus mensurabilis ad modum ytalicorum’ di Prosdocimo de Beldemandis, Firenze: Olschki, 1938.

Sucato 2007

Marchetto da Padova, Lucidarium. Pomerium, ed. Marco Della Sciucca, Tiziana Sucato, Carla Vivarelli, Firenze: Galluzzo, 2007.

Wolf 1919

Johannes Wolf, Handbuch der Notationskunde, 2 voll., Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1913-1919.